From one nightmare to another

KOH LIPE, Thailand, May 15, 2015 - For us this story began several weeks ago with the discovery of a mass grave in southern Thailand, thought to hold the bodies of Rohingya migrants smuggled into the country from neighbouring Myanmar.

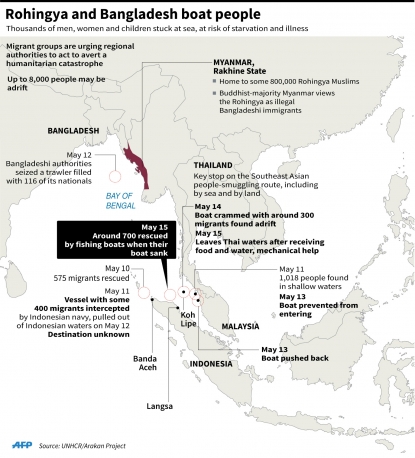

The stateless Rohingya are one of the world’s most persecuted minorities according to the United Nations. Tens of thousands have fled Myanmar since communal violence broke out between them and the ethnic Buddhist Rakhine in 2012. Though the overall picture is murky, it is widely suspected that thousands are being trafficked out of the country on a route that runs via southern Thailand, where they are held by smugglers in squalid camps before being taken on, mainly to Malaysia.

(AFP Photo / Christophe Archambault)

(AFP Photo / Christophe Archambault)The discovery of the bodies – and reports of dozens more graves lying undetected – sounds a wake-up call for the Thai authorities who vow to smash the trafficking networks, and stop the migrant boats from landing on their shores.

But their clampdown comes at the height of the migration “season”, with dozens of smuggler boats out at sea, carrying hundreds if not thousands of men, women and children, and unable to reach Thai shores as planned. So the traffickers start abandoning their boats, even sabotaging the engines, and leaving them adrift in the waters between Malaysia and Thailand.

(AFP Photo / Christophe Archambault)

(AFP Photo / Christophe Archambault)After a few days we hear, via an NGO, of a boat drifting without food or water, on which migrants have telephoned to say they can see land. We decide to try to get to the boat, thought to be off the coast of southern Thailand.

One-off chance

We know it won’t be easy. There are hundreds of islands in the area, and scores of small boats. But it’s a one-off chance to document this dramatic story.

The Thai authorities are initially helpful, offering to take us out on patrol close to Malaysia’s territorial waters. So we fly to the southern town of Hat Yai, head on to Satun on the coast, and board a speedboat the following morning for the island of Koh Lipe where the patrol is due to leave.

(AFP Photo / Christophe Archambault)

(AFP Photo / Christophe Archambault)But when we turn up at the appointed time, we are informed of a change of plan. It turns out the Thai authorities have located the boat, presumably using telephone GPS data. But the half dozen media crew including ourselves who were hoping to join them are no longer welcome.

‘Out of the question,’ the soldiers tell us. ‘We have our orders: no journalists on board.’

Lives in the balance

Incredibly frustrating, needless to say. It has taken 36 hours to get to this point, and there is nothing else for us to do on Koh Lipe, a typical Thai tourist island.

We are here to document a terrible situation, with people’s lives hanging in the balance. We absolutely must reach the boat. So together with two local Thai media crew, we rent a speed boat and set off on our own.

(AFP Photo / Christophe Archambault)

(AFP Photo / Christophe Archambault)I had managed to identify from our dealings with the Thai authorities the general area where the boat was thought to be drifting. And crucially, one of our fellow passengers was a Thai journalist in telephone contact with a migrant on board.

A situation of absolute horror

We set out to sea. Nothing on the horizon. I fear we will never find them. And then suddenly, there it is right before our eyes. A boat perhaps 20 metres long, crammed with about 300 people. Men, women, children, babies.

(AFP Photo / Christophe Archambault)

(AFP Photo / Christophe Archambault)My first reaction is shock. We are faced with people who have not eaten in days, maybe even weeks. We had heard of people drinking their own urine to survive. Their faces are completely emaciated, their hair long and straggling. You can see their ribcages, their pointed shoulder bones.

We are witnessing a situation of absolute horror. One young guy must weigh no more than 35 kilos.

(AFP Photo / Christophe Archambault)

(AFP Photo / Christophe Archambault)Here are two worlds just a few metres apart: utter misery on one hand, and us, comfortable in our speedboat on the other. And all this just 15 kilometres from Koh Lipe, a tourist paradise where people come for deep-sea diving.

Desperate eyes

The people on board start crying, shouting, jostling to see us, looking at us with desperate eyes. They gesture to show they are hungry, close to dying of thirst. With us there is an interpreter who speaks Rohingya. They tell us 10 people have died since their journey began.

(AFP Photo / Christophe Archambault)

(AFP Photo / Christophe Archambault)We look around ourselves. We have no food, perhaps 10 bottles of water. Should we throw them up, or would that risk causing a stampede? In the end we throw them our water, and promise we will wait until help comes.

We see some Thai fishing boats draw near and, touchingly, share with the Rohingya what little they have. It is almost dusk when a navy helicopter carrying food rations arrives overhead. It can’t drop anything on the boat’s deck board since there is no room. So it is logical enough to throw the rations in the water. And yet to see migrants go plunging after them makes for powerful images.

They are driven by raw hunger. At one point there are about 20 young men in the water, trying to stop the packages from drifting off.

(AFP Photo / Christophe Archambault)

(AFP Photo / Christophe Archambault)Two images will really stay with me. One shows a guy ripping open a packet of dried noodles and eating them in the middle of the ocean. He had to eat immediately. And this other one, showing two guys half-hidden under the hull of the boat, devouring a food ration as he looks straight at me. As if saying, ‘Yes, I know I need to take up food to the others, but first I must eat.’

A human face on the crisis

Eventually the young men are all helped back on board by fishing boats and the navy boat that had returned by that point. We throw a life belt out to one of them. We leave as night falls. The migrant boat’s engine is repaired overnight, allowing them to set off on their journey in the early hours.

(AFP Photo / Christophe Archambault)

(AFP Photo / Christophe Archambault)Three years ago I visited Rohingya camps in Buddhist-majority Myanmar, where I witnessed people from the Muslim minority living in utter squalor – their women literally giving birth in the mud. Even those who survive the perilous migration and make it to Malaysia risk ending up working in slave-like conditions on farms. And yet even that is seen as preferable to the living nightmare they face in Myanmar.

I have felt very strongly about the Rohingya’s story ever since making that trip. We are here in the hope our pictures can put a human face on this crisis. If enough people are touched by these images of despair, perhaps it will force politicians to act.

Christophe Archambault is AFP chief photographer in Thailand. He has been reporting from southern Thailand along with Preeti Jha and Thanaporn Promyamyai.