'If you find my dead body…'

PARIS, May 13, 2015 – Jean-Marie Le Pen is not much of a talker on the phone. More often than not, he’ll pick up and answer your first question with a courteous wisecrack, before hanging up on you. Which leaves you none the wiser.

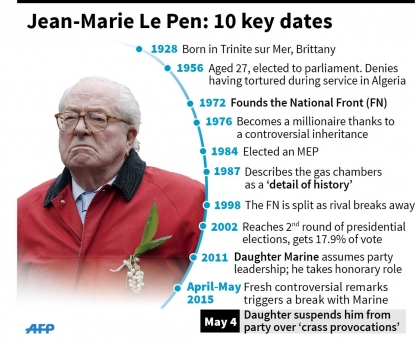

This time is different. On the evening of May 4, a Monday, the historic leader of France’s far-right National Front party is in the mood for talking.

An hour earlier, the FN’s political bureau suspended his membership. The party’s top body also called an extraordinary congress to strip from its status books the position of “honorary president”, which the 86-year-old firebrand had claimed for life.

It is the most serious episode to date in the crisis opposing Jean-Marie Le Pen and his daughter Marine, who took over the party leadership from him in 2011.

Jean-Marie Le Pen and his daughter Marine at the paternal home in Saint-Cloud, west of Paris, on November 22, 2010

(AFP Photo / Miguel Medina)

In the news rush of that busy day I suddenly spot an exclusive reaction from Le Pen to his suspension – filed by my colleagues at French radio Europe 1.

I scroll through my phone contacts for “JM Le Pen” and dial his number. As I have done countless times since the start of April as the patriarch openly, and repeatedly defied his daughter, who has been working to strip the far-right party of its most controversial characters and trappings and cast it as ready to govern.

'An act of treason'

The rift played out over several weeks, beginning when Jean-Marie Le Pen repeated an oft-held assertion that the Nazi gas chambers were a “detail” of history, a stance that has already earned him a court conviction. A few days later he called for the preservation of the “white world,” before rising to the defence of Marshal Petain, France’s collaborationist leader during the Nazi occupation in World War II.

At 9:30 pm, Le Pen picks up the phone and appears ready to talk. I get the feeling he was waiting for my call.

His suspension from the party? “An act of treason!” he fumes.

Marine Le Pen in January 2012, and Jean-Marie Le Pen in May 2014 (AFP Photo / Joel Saget / Guillaume Souvant)

Marine Le Pen in January 2012, and Jean-Marie Le Pen in May 2014 (AFP Photo / Joel Saget / Guillaume Souvant)“I have asked Marine Le Pen to give me back my name,” he goes on, aiming a first, poisonous arrow at his estranged child: “She can do that by getting married, either with her concubine, or with someone else – why not Philippot.” In one sentence he also skewers two top figures of the FN: Marine’s partner Louis Aliot who he will not stoop to call by name, and her right-hand man Florian Philippot.

Going mainstream

Le Pen co-founded the FN in 1972 and led the party until January 2011, keeping it afloat through years of financial hardship and troubles - brought on in part by his own incendiary antics in the media, and a somewhat ruthless approach to internal democracy.

And yet he was disciplined like a rank-and-file activist over the accumulation of comments that flew in the face of his daughter’s ambition to turn the FN into a mainstream party.

National Front vice-president Louis Aliot and Marine Le Pen on a flight to the Italian island of Lampedusa in 2011

(AFP Photo / Christophe Simon)

She had never gone this far before. When Jean-Marie Le Pen declared back in 2005 that the German occupation “was not particularly inhumane” in France, Marine remained silent, simply withdrawing from the political spotlight until the storm had passed.

A few years on, she drew a line much more clearly between herself and her father, by describing the Nazi gas chambers as “the height of barbarity.”

In June 2014, when her father suggested cooking up an “ovenful” of artists hostile to the FN after he was asked about the Jewish singer Patrick Bruel, she called it a “political fault”. She took him to task, not so much for his words as for his failure to anticipate their consequences. This time, though, Marine Le Pen decided enough was enough.

Gatecrashing the party

At the other end of the line, Jean-Marie Le Pen is still talking, appealing now to the FN’s members: “They will be outraged by such treason, at least those who have a sense of honour.”

Me : “You believe the party members are behind you?”

Le Pen: “That was pretty clear the other day, when I came on stage at the Place de l’Opera. The crowd’s welcome was unequivocal. I didn’t steal that. And I didn’t inherit it either.”

Jean-Marie Le Pen sings at the foot of a statue of Joan of Arc at a May 1 rally in Paris in 2015 (AFP Photo / Thomas Samson)

Jean-Marie Le Pen sings at the foot of a statue of Joan of Arc at a May 1 rally in Paris in 2015 (AFP Photo / Thomas Samson)Ouch. Another arrow. Three days earlier at the party’s traditional May Day gathering in honour of Joan of Arc, Jean-Marie Le Pen burst on stage uninvited, just as his daughter was about to deliver her speech. “What a rascal,” mused one of his old allies.

All Le Pen in once sentence

By this point I figure I have just about wrapped up my interview, and I’m preparing to hang up, when he adds, with a flourish: “Dear sir, if they find my dead body rest assured I will not have committed suicide.”

My first response is to laugh. I hear him chuckling too.

But that one sentence, delivered as the punch line to our conversation, just about sums up the character.

National Front keyrings, one of them reading: 'France, love it or leave it!', in 2006 (AFP Photo / Joel Saget)

National Front keyrings, one of them reading: 'France, love it or leave it!', in 2006 (AFP Photo / Joel Saget)Listening to the interviews he gave to various media in the following days, the pitch is largely the same. These are anything but emotive outbursts. The veteran politician is sometimes nicknamed “Le Menhir” (The Dolmen) for his Breton origins. He cannot be easily rocked. And his answers are perfectly prepared.

Le Pen is a complex character, both an erudite with a rich knowledge of history and a relentless provocateur. It takes time to figure him out.

I have been covering the far-right party since 2013. My first big splash came in May 2014, a few days before the European elections, when Le Pen pere was running for a seat in southeast France and his daughter was in Marseille to support him.

I was there to cover the election run-up but also to gather material for a story on what would in all likelihood be Le Pen’s last campaign. With that in mind, I was sticking close to the “Old Man”, as his detractors within the party sometimes call him, at the cocktail reception organised for the press – something of a rarity for the FN.

'Monseigneur Ebola'

Le Pen was there surrounded by a handful of supporters, but very few journalists – most of whom were listening to Marine in the room next door. He was holding forth in his usual register, warning of the perils of mass migration and drawing ominous comparisons between Europe and the rest of the world, “seven billion people” with an explosive birthrate.

A National Front rally for the 2012 French presidential election in Nice, southern France (AFP Photo / Boris Horvat)

A National Front rally for the 2012 French presidential election in Nice, southern France (AFP Photo / Boris Horvat)But this time he threw a new ingredient into the mix, inspired by the deadly tropical fever that had recently surfaced in West Africa. “Monseigneur Ebola,” he suggested, could settle the European immigration crisis in three months.

Keep saying something until it gets picked up

Jean-Marie Le Pen appears to care little about the migrants who die crossing the Mediterranean to reach Europe. His outrageous comments sounded like front-page material to me, so I wrote a story about them.

The next day I learned from colleagues that Le Pen said the same thing at a recent dinner. The journalists present were surprised enough, but dismissed the outburst as a ploy for attention. None of them published his words.

Sure enough, I would soon find out that Jean-Marie Le Pen repeats his outrageous snippets until someone or other picks them up in the media.

Le Pen may be physically diminished, as shown by a recent spell in hospital for heart trouble. But he is far from the senile old man some would paint him as. He knows exactly what he is doing.

Jean-Marie Le Pen does push-ups after a swim in La Baule beach resort in 1994 (AFP Photo / Frank Perry)

Jean-Marie Le Pen does push-ups after a swim in La Baule beach resort in 1994 (AFP Photo / Frank Perry)In the summer of 2014, I interviewed him in the office of his manor in Montretout, part of the well-heeled Paris suburb of Saint Cloud. He received me surrounded by portraits and books, including the complete works of Robert Brasillach, an anti-Semitic writer and Nazi collaborator who was shot after France’s Liberation in 1944. There was also a picture of Marine Le Pen embracing her father. Is it still there, I wonder?

'Row over a burnt omelette'

In the July heat, Le Pen offered up political insights, spoke of his vision of history, talked fondly of Marine and his grand-daughter Marion. He also shared a few crunchy anecdotes – like the time he wound up with his pants around his ankles moments after leaving the stage at a rally, having just been on a strict diet.

He made light of past differences with his daughter, including the one over his “ovenful” comments. “A domestic row over a burnt omelette,” he joked.

Jean-Marie and Marine Le Pen in May 1974 (AFP)

Jean-Marie and Marine Le Pen in May 1974 (AFP)Does he feel compelled to provoke? “I am a free man,” he said. But what about staying within certain boundaries? “In the name of what? I have my own conscience!”

To prove his point – that he upsets no one but journalists – he cited an example: “I went to a black wedding recently. Black people, but very nice, very well dressed.” He was given a rapturous welcome, he claims. “My doctor told me I should stand for office in Africa!” And he burst out laughing.

‘Lots of gays in the FN’

He also told me that day that the FN now counted “quite a lot of gays” among its members.

“They are people with time on their hands. I have no problem with them, so long as they don’t go slipping their hands in my pants, or those of our little boys and girls.”

Le Pen was quite happy for me to print the whole contents of our two-hour interview, with the exception of a single sentence, which he asked to remain off-the-record.

Jean-Marie Le Pen at his home in Saint Cloud near Paris in October 2012 (AFP Photo / Bertrand Guay)

Jean-Marie Le Pen at his home in Saint Cloud near Paris in October 2012 (AFP Photo / Bertrand Guay)If the veteran politician has one merit, it is to be utterly upfront about his tactics. Provocation, as far as he is concerned, is a useful tool. One that helps the FN make gains. “No one wants a tame FN,” he has said, over and over.

“Joining the establishment means death,” he insists.

So Jean-Marie provokes, and we journalists are on the receiving end. Up to us to judge when his comments are newsworthy, or when publishing them simply plays along with his strategy.

In my story on our conversation of May 4, I quoted the piques aimed at his daughter, the line about his “dead body”. But I tried to keep my headline focused on the news: Le Pen calling his suspension “treason”, and reaching out to party activists to oppose Marine.

And yet, sign of the public appetite for his outbursts, my “dead body” quote was retweeted 270 times. A colourful line which, as my fellow journalist and FN expert David Doucet later told me, Jean-Marie Le Pen had tried to spin out once before…

Guillaume Daudin is a political reporter for AFP in Paris, in charge of covering the National Front

Jean-Marie Le Pen stands as witness as the Marquis Georges de Cuevas (L) readies to duel with the dancer Serge Lifar in a field outside Paris on March 30 1958 (AFP / Intercontinentale)

Jean-Marie Le Pen stands as witness as the Marquis Georges de Cuevas (L) readies to duel with the dancer Serge Lifar in a field outside Paris on March 30 1958 (AFP / Intercontinentale)