Mass shootings: the other innocent victims

Every time there is a mass shooting in the United States, innocent people get blamed, falsely identified on social media as the shooter, writes AFP’s Bill McCarthy, who has debunked many of the fake posts

The news, flashed across a television in AFP’s Washington bureau, told a story that has become numbingly familiar in America. A heavily-armed shooter had opened fire inside the Covenant School in Nashville, Tennessee, adding six more names to the long list of innocents killed by gun violence in the United States. Three were children, all nine years old, massacred by a stranger.

Whenever another mass shooting happens, my heart sinks – not just for the victims, their loved ones and the communities shattered by grief. It sinks because I also know from my work as a digital investigation journalist for AFP’s North America fact-checking team that other blameless people will be falsely accused of being the killer, their pictures shared all over the web by social media users.

I have seen the pattern play out over and over. Every time a mass shooting happens, a misinformation story begins. After February’s shooting at Michigan State University, a writer from Massachusetts who had nothing to do with the attack was blamed by a hoaxer on Twitter, complete with a fake Facebook post mocked up in his likeness.

A mouner breaks down at a vigil for the victims of the Covenant School shooting in Nashville, Tennessee on March 29, 2023 (AFP / John Amis)

A mouner breaks down at a vigil for the victims of the Covenant School shooting in Nashville, Tennessee on March 29, 2023 (AFP / John Amis)

When a gunman killed revellers at an LBGTQ nightclub in Colorado Springs in November, social media users peppered the internet with photos they claimed showed the suspect. The pictures were actually of a professional hockey player and a North Carolina man among others.

And after another school was stormed in Uvalde, Texas last May, users of the 4chan message board, which has little regulation, poached pictures of a transgender woman from Reddit and falsely claimed they showed the gunman.

Nashville was no different. After the massacre, photos of a comedian, a transgender video games streamer, an artist on the Etsy crafter website and an Oklahoma protester spread across the internet.

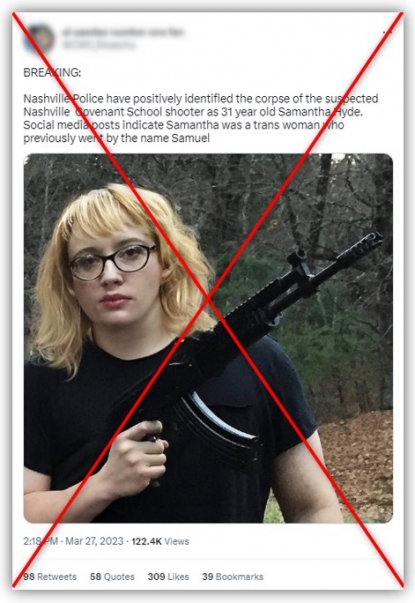

A Twitter post falsely identifying the shooter

A Twitter post falsely identifying the shooter Wrongly accused: Clara Sorrenti, a transgender activist and target of online harassment

Wrongly accused: Clara Sorrenti, a transgender activist and target of online harassment

It is human nature to want to know more about such terrible events. And there is a certain fascination with who the killer could be. But gaps in information as law enforcement and journalists work out what happened leave space for speculation across social media, and exploitation by bad actors. And the harm they do is real.

Shortly after police said they had responded to a shooting, I opened Twitter and ran a simple keyword search: “Nashville shooter identified.” According to dozens of results, the city’s officials had already singled out the perpetrator. It was a transgender woman named “Samantha Hyde”, the posts claimed.

Sam Hyde, an American comedian, is a familiar name for fact-checkers. So are variations, such as “Samantha Hyde”, “Samuyil Hyde” and “Samir Al-Hajeed”. Internet users have sought to trick people into believing Hyde was behind countless tragedies over the years, smearing his name as part of a long-running hoax that originated as a meme on 4chan.

Other tweets from a since-deleted page tried to pin the attack on Clara Sorrenti, a transgender activist and video game streamer known online as “Keffals”, who was forced to flee her Canada home last year after being targeted by an online harassment campaign.

By evening, Nashville police had named the shooter as someone else: Audrey Hale, 28, who died in a shootout with officers, and who police said identified as transgender.

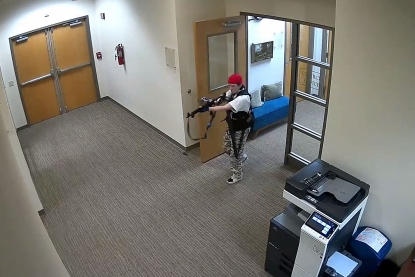

A police grab of shooter suspect Audrey Hale at the Covenant School (AFP)

A police grab of shooter suspect Audrey Hale at the Covenant School (AFP)

But the revelation did not put the misinformation to rest. Instead, it sent social media users hunting for pictures of Hale, and within minutes Twitter and other platforms were littered with images that claimed to show the suspect. I raced to verify them, using reverse image search engines such as TinEye and checking other users’ comments for clues about their authenticity.

Some photos appeared real. There was the headshot released by police, and another scraped from a LinkedIn profile reportedly belonging to Hale. Others, I found, did not show Hale at all.

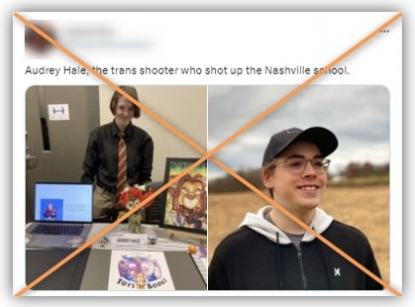

Then I saw a video on TikTok from a bespectacled 19-year-old from Pennsylvania. “Apparently I’m being confused with the Nashville incident that happened today. I have nothing to do with that. I live in Pennsylvania.”

The photo of the teenager, who sells dioramas of old buildings on Etsy under the title “Aiden Creates”, was already viral, amplified by Donald Trump Jr, the former US president’s son. Aiden is the name Hale used on some social media accounts, according to reports.

A Twitter post falsely accusing the teenager (right) of being the Nashville shooter

A Twitter post falsely accusing the teenager (right) of being the Nashville shooter

Another picture of an Oklahoma activist with a sign that said “Trans rights… or else” spread in posts claiming it showed Hale, despite the photographer’s attempts to correct those claims.

The posts underscored how misinformation almost always outpaces efforts to debunk it – a reality that can feel especially overwhelming in the high-stakes moments after crisis events.

The night of the Michigan State University shooting, police even received tips based on the fake Facebook post created in the Massachusetts writer’s name.

The mind boggles as to what could be possible as artificial intelligence technology continues to advance. One of this week’s most viral images was a deep fake AI photo of a hipsterish Pope Francis wearing a full-length white puffer coat.

And on Wednesday 1,000 tech leaders including Elon Musk called for a moratorium on powerful AI development citing “profound risks to society and humanity”. Yet moderation policies governing platforms such as Twitter, which Musk owns, are being relaxed.

The consequences extend beyond the confusion caused. How is a person to go on with their life when their name or picture has been linked to the murder of innocent people?

The Pennsylvania Etsy artist pleaded for help in a video, originally on TikTok. There was little more they could do. “If you see any of these posts anywhere that have my photo in it, please report it,” the teenager asked.

But the damage has been done and truth has taken another battering.

Edited by Arthur MacMillan in Washington and Fiachra Gibbons in Paris