‘Stalin is dead’: the story behind the scoop

Word began to leak out after World War II that Joseph Stalin was not a well man. Rumours – which were impossible to verify – had it that “the man of steel” was so worried about his failing health that he was seeing doctors morning and night. They were also injecting him with a “super serum” to stop him ageing.

The Georgian-born Soviet leader was seen less and less from the early 1950s, spending most of his time in his dacha at Kuntsevo in the Moscow suburbs. His last public appearance was in October 1952 when he closed the 19th Congress of the Communist Party of the USSR.

Such was the stranglehold of Soviet censorship, that getting news out quickly from AFP’s Moscow bureau would be well-nigh impossible. So the agency had a team of Russian-speaking journalists in Paris listening in on Radio Moscow’s internal programmes day and night for any hint of Stalin’s health, as well as keeping a sharp eye on the news ticker from the Soviet press agency TASS.

AFP beat its rivals to the news that the Soviet leader was gravely ill (AFP )

AFP beat its rivals to the news that the Soviet leader was gravely ill (AFP )

Some were eminent Russian emigres like Arkady Stolypin, the son of Tsar Nicholas II’s prime minister Pyotr Stolypin, who was assassinated at the opera in Kyiv in 1911, having survived 10 other plots on his life.

One of them, known rather formally as Mr Volokhine, was the first to discover that the dictator’s health had suddenly deteriorated at dawn on March 4, 1953. “It had been a really quiet night,” he recalled later. “I was listening to Radio Moscow at 6 am and was expecting one of their routine bulletins when suddenly there was just music, which lasted until 6.30.

“It was a bit strange. It was near the end of my shift – I’d have been gone in 10 minutes – when Yuri Levitan, that terrible, haunting voice of Radio Moscow we heard during the war came on to make this thunderous announcement: ‘Stalin. Cerebral haemorrhage. Right side paralysed.’

“The Radio Moscow signal was very crackly so I went to my recording disc to listen to it again to make sure we had it all. Ten minutes later the news was on the wire.”

“Stalin has had a cerebral haemorrhage that has affected vital parts of his brain. His right leg and arm are paralysed, he has lost consciousness and he cannot speak.”

AFP’s monitoring team went into maximum alert, with three Russian-speaking journalists and two editors working 24 hours, sending out the meagre updates they could glean on Stalin’s condition.

In the early hours of March 6, Radio Moscow interrupted its normal programmes to declare in a grave and solemn tone that an important announcement would soon be made. Classical music began to play, only to be mysteriously interrupted again and again by the sound of a ticking clock.

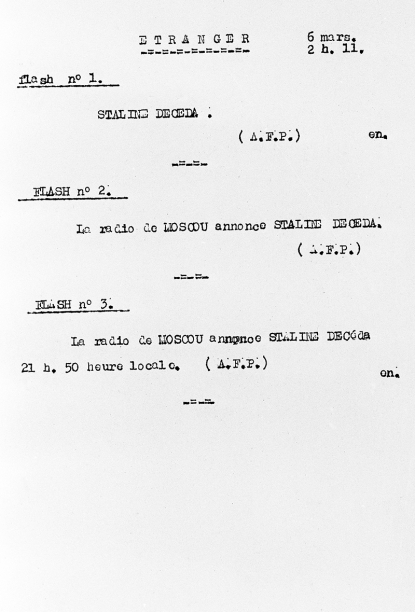

The first two AFP 'flashes' breaking the news of Joseph Stalin's death on March 6, 1953 (AFP)

The first two AFP 'flashes' breaking the news of Joseph Stalin's death on March 6, 1953 (AFP)

Then, a little after 2 am, a voice declared: “Stalin is dead.”

The journalist who relayed the news to the world was Alexis Schiray, the head of AFP’s Russian monitoring service, who had spent three days and nights at his post, earphones clamped to his head. He got the “flash” on the wire five seconds after the words crackled out of Radio Moscow’s internal service.

A little later on in the next news bulletin – preceded as always by the Soviet national anthem – the official statement was read with such slow, funereal gravity that every single syllable was pronounced. Stalin, it said, had died at 9.50 pm local time the night before from heart and lung failure.

Because information travelled so much slower then, AFP’s lead on rival news agencies was up to an hour and a half by the time the news reached southeast Asia and Latin America.

The rest is history. Stalin’s remains were transferred to the House of the Unions in the centre of Moscow. By that afternoon it was lying in state, with the first of some five million Soviet citizens queuing to pay homage to the man who had ruled them with an iron fist since 1928. The queue stretched 10 kilometres (six miles) at one stage.

Soviet leaders march behind Stalin's coffin at his state funeral in the Kremlin on March 9, 1953 (AFP / TASS)

Soviet leaders march behind Stalin's coffin at his state funeral in the Kremlin on March 9, 1953 (AFP / TASS)Behind the scenes, the battle to succeed him had started, a struggle that would later be played for laughs in the 2017 black comedy, “The Death of Stalin”. One of the dictator’s closest advisors, Nikita Khrushchev, eventually won out and began a de-Stalinisation process after denouncing his old boss and his cult of personality in his “secret speech” to party cadres three years later. Stalin’s body was removed from Lenin’s tomb in the Kremlin and thousands of his statues were taken down.

Despite his bloody legacy, with millions murdered during his purges, Stalin’s stock has rising steadily under Vladimir Putin. Many ordinary Russians have more than a grudging respect for him.

Putin has invoked comparisons between Stalin’s firm leadership during what Russians call the “Great Patriotic War” and his own invasion of Ukraine, which he portrays as a special operation to “de-Nazify” the country.

Last month, on the eve of the 80th anniversary of the end of the Battle of Stalingrad that turned World War II, a bust of the dictator was unveiled in the city, now known as Volgograd.

Stalin admirers leave flowers at his tomb on Moscow's Red Square in December 2022 (AFP / Alexander Nemenov)

Stalin admirers leave flowers at his tomb on Moscow's Red Square in December 2022 (AFP / Alexander Nemenov)