Ukraine: When things fall apart

Kiev - The night the war began on February 24, AFP photographer Daniel Leal slept in his clothes in his hotel room in Kyiv. He didn't even take out his contact lenses. Word had gone around that it would start “tonight”.

“How can you sleep when you are waiting for war,” Daphne Rousseau wrote in her diary. She had arrived from Paris four days earlier to back up the Kyiv bureau. “I smoked cigarette after cigarette on the balcony, watching the sky... I put on a podcast on my phone -- Dostoevsky's 'The Brothers Karamazov' -- and stuck it under my pillow. “It vibrated every time there was a notification. I read them all in the dark.”

Dmytro Gorshkov didn't believe it would come to war. “Everyone thought it could be averted,” said the Ukrainian editor who has worked for AFP in Kyiv since 2013. “That night I was at my home with my wife and son” in a residential district in the north of the capital. Everything was normal.

A view of the Independence Monument and a sign I love Ukraine in central Kyiv early on February 24, 2022. (AFP / Daniel Leal)

A view of the Independence Monument and a sign I love Ukraine in central Kyiv early on February 24, 2022. (AFP / Daniel Leal)

But 900 kilometres (560 miles) to the east in Moscow, Russia bureau chief Antoine Lambroschini had a knot in his stomach. “I was convinced there would be a Russian offensive but I kept hoping that I was wrong.

“My brother and his family, who have lived in Ukraine for nearly six years, had just left Kyiv fearful that an assault was imminent. That night I went out with my wife Sofiya and some friends to a trendy Moscow restaurant. Ukraine was on everyone's lips, but no one thought it could happen, 'Not in 2022!'”

But then came a late call from the office. “The pro-Russian separatists in the Donbass appealed to Putin and the Russian army to rescue them. It was the beginning of a long night for me and my colleague, Ola Cicowlas.

“Then President Volodymyr Zelensky appeared on our screens, Lambroschini recalled. His voice was grave as he spoke movingly in Russian, speaking directly to the Russian people, pleading with them to pressure Vladimir Putin into stopping the tragedy that was about to unfold.”

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky holds an urgent meeting with the leadership of the government, after the launch of Russia's military operation against Ukraine, in Kyiv early on February 24, 2022. (AFP / Handout)

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky holds an urgent meeting with the leadership of the government, after the launch of Russia's military operation against Ukraine, in Kyiv early on February 24, 2022. (AFP / Handout)

“When things get this serious, you can hear it in your colleagues' voices. They tremble a little with emotion, fear and fatigue. By 3.30 in the morning the last of our reports were out on the wire. We could go to bed at last. But we slept lightly.

“Barely an hour and a half later, Tom Lowe, a colleague in Hong Kong, woke me. The Asia desk kept an eye on things while we slept, and Tom had seen some worrying signs on Twitter.

“Something was happening on the Russian-Ukrainian border. Aviation websites were showing commercial aeroplanes avoiding Ukraine. Rumours of explosions were flying. I woke the head of our Ukrainian bureau, Ania Tsoukanova. 'Something is happening,' I told her.

A picture of the Flightradar 24 website that shows the absence of civilian flights over Ukraine on February 24, 2022 (AFP / Loic Venance)

A picture of the Flightradar 24 website that shows the absence of civilian flights over Ukraine on February 24, 2022 (AFP / Loic Venance)

“Around 5.40 am Moscow time, Putin appeared suddenly on television. I knew what was coming. My heart began to thump...

“He began repeating a litany of Ukraine's wrongs, and those of the West and NATO, saying Russian speakers in Ukraine were suffering a genocide at the hands of Ukrainian 'Nazis'. It was chilling. You could feel his anger. As I sat there alone in my pyjamas, I felt a little incredulous at the enormity of what was happening as my wife and children slept a few metres from me.

“I was so afraid of missing a word, I didn't call anyone other than my colleagues from video and photo. Our alert at 5.50 am Moscow time broke the news to the world: 'Russia's Putin announces a 'military operation' in Ukraine.'”

Explosions were soon heard in several cities. War had begun.

Smoke rising after an explosion in Kyiv on March 16, 2022 (AFP / Aris Messinis)

Smoke rising after an explosion in Kyiv on March 16, 2022 (AFP / Aris Messinis)

AFP's Paris headquarters quickly kicked into action. Work had been going on for several days on setting up a safer rear base in the western city of Lviv, close to the Polish border.

Logistics specialist Karim Menasria had just returned to Paris after spending 44 days in the Covid bubble for the Winter Olympics in Beijing. Now he was going to have to leave again for Ukraine with bulletproof vests, helmets, generators and electronic equipment.

Three days later Karim was at the Ukrainian border with a car bought in Poland bursting with equipment. He had also somehow squeezed reporter Emmanuel Duparcq and AFPTV journalist Colin Bertier aboard along with 20 jerrycans, petrol being a priceless commodity in a war zone.

While AFP's priority is always to get people on to the ground fast, they have to be kept safe. The special correspondents that had been sent to back up our bureau in Kyiv since the start of February were now joined by a new wave of reinforcements. More than 20 vastly experienced reporters, video journalists, photographers - many of whom earned their stripes in similar situations - pour in from Paris, Istanbul, Bucharest, Athens, Moscow and our Middle East desk in Nicosia…

By dawn on February 24, the seemingly carefree Ukrainian capital of the night before was no more. This was the limbo between peace and war.

Kyiv metro station, early on February 24, 2022. (AFP / Daniel Leal)

Kyiv metro station, early on February 24, 2022. (AFP / Daniel Leal) People hug as a woman with a suitcase passes by outside a metro station in Kyiv in the morning of February 24, 2022. (AFP / Daniel Leal)

People hug as a woman with a suitcase passes by outside a metro station in Kyiv in the morning of February 24, 2022. (AFP / Daniel Leal)

Photographer Daniel Leal left his hotel at 5.30 am wearing a helmet and a bulletproof vest.

“That morning the faces changed. Everyone was distressed. Women were saying goodbye to their partners... people were hugging on the metro.” Daniel captured the long, lingering embraces of couples who did not know if they would see each other again, while around them commuters were still going to work as usual.

As the day wore on, people began to flood towards the city's stations with their children and their pets.

“As a father myself, I identified especially with the parents and the children,” said Daniel, who is normally based in London. “I have a seven year old, a five year old and a baby on the way. It really broke my heart. I could not help but to see myself in their situation.”

And yet in the days leading up to the invasion, Daniel had been so impressed by Kyiv, by its architecture, its “majestic” avenues and its welcoming people that he had thought of bringing his family there one day.

(AFP / Daniel Leal)

(AFP / Daniel Leal) Helena, a 53-year-old teacher stands outside a hospital after the bombing of the eastern Ukraine town of Chuguiv on February 24, 2022 (AFP / Aris Messinis)

Helena, a 53-year-old teacher stands outside a hospital after the bombing of the eastern Ukraine town of Chuguiv on February 24, 2022 (AFP / Aris Messinis)

But for Daniel's Ukrainian colleagues, Kyiv was home and the unthinkable was now happening. “It is their lives, their children, everything they have built,” said Daphne Rousseau.

The six staff based in AFP's Kyiv bureau had to decide whether to stay or go. Ukrainian men aged between 18 and 60 are not supposed to leave the country. Those who do are considered deserters.

Ukrainian servicemen get ready to repel an attack in Ukraine's Lugansk region on February 24, 2022. (AFP / Anatolii Stepanov)

Ukrainian servicemen get ready to repel an attack in Ukraine's Lugansk region on February 24, 2022. (AFP / Anatolii Stepanov) A Ukrainian serviceman stands guard near a burning warehouse hit by a Russian shell in the suburbs of Kyiv on March 24, 2022. (AFP / Fadel Senna)

A Ukrainian serviceman stands guard near a burning warehouse hit by a Russian shell in the suburbs of Kyiv on March 24, 2022. (AFP / Fadel Senna)

Dmytro Gorshkov and photographers Sergei Supinsky and Genya Savilov decided to stay in Kiev. However, Dmytro persuaded his wife to move to the west of the country with their 14-year-old son. He would stay behind to report on the war and look after his mother and his 89-year-old grandmother.

Children look out from a carriage window as a train prepares to depart from a station in Lviv, western Ukraine, en route to the town of Uzhhorod near the border with Slovakia, on March 3, 2022. (AFP / Daniel Leal)

Children look out from a carriage window as a train prepares to depart from a station in Lviv, western Ukraine, en route to the town of Uzhhorod near the border with Slovakia, on March 3, 2022. (AFP / Daniel Leal)

Europe has seen other wars since 1945, but Ukraine is different. How do you cover a conflict on so many fronts which also involves a superpower that has put its nuclear forces on high alert?

Even beyond the nuclear threat, the implications were huge. Millions across the Middle East and beyond depend on Ukrainian grain for their daily bread. The US ambassador to the United Nations, Linda Thomas-Greenfield, warned that up to five million people could be turned into refugees. We now know 10 million have been driven from their homes in the space of a month.

Kyiv was being gripped by rumours that the Russians had infiltrated the city. To root out the interlopers, security forces asked people at checkpoints to say the word “palyanytsa”. It means strawberry in Russian but it is also the name of a traditional Ukrainian bread. Those who didn't stress the long “a” at the end were likely to be suspect.

Ukrainian policemen stop cars to control people as they look for suspicious men, on February 27, 2022 in a street of Kyiv (AFP / Aris Messinis)

Ukrainian policemen stop cars to control people as they look for suspicious men, on February 27, 2022 in a street of Kyiv (AFP / Aris Messinis) A member of the Ukrainian forces patrols in Kyiv, on February 27, 2022. (AFP / Aris Messinis)

A member of the Ukrainian forces patrols in Kyiv, on February 27, 2022. (AFP / Aris Messinis)

AFP teams fanned out across Ukraine's many fronts. Photographer Sergey Bobok was in Kharkiv in the east. Ukraine's second city, just 40 kilometres from the Russian border.

Living under constant bombardment, Olena Ostaptchenko told him she felt like she was in a World War II film. Olena now lives between her “bathroom and the corridor”, the only places in her apartment where she feels any way safe.

A woman walks near a damaged apartment building in Kharkiv, Ukraine, on March 8, 2022. (AFP / Sergey Bobok)

A woman walks near a damaged apartment building in Kharkiv, Ukraine, on March 8, 2022. (AFP / Sergey Bobok) Kharkiv, on March 8, 2022 (AFP/ Sergei Bobok)

Kharkiv, on March 8, 2022 (AFP/ Sergei Bobok)

Other reporting teams headed out to Irpin, only eight kilometres north of Kyiv. Key to any advance on the capital, it was being pummelled by the Russian army. Aris Messinis' photographs of the plight of its despairing inhabitants fleeing their burning homes sear into the memory.

Irpin, outside Kyiv, on March 4, 2022 (AFP / Aris Messinis)

Irpin, outside Kyiv, on March 4, 2022 (AFP / Aris Messinis) Irpin, on the outskits of Kyiv, on March 4, 2022. (AFP / Aris Messinis)

Irpin, on the outskits of Kyiv, on March 4, 2022. (AFP / Aris Messinis)

Oleksei Ivanovitch did not want to leave his home even when Russian tanks took the neighbouring town of Boutcha.

“It was my son and grandson who made me go,” he told reporter Emmanuel Duparcq. And now here he was at 86 having to walk a trapeze of planks laid across a river to escape the bombardment.

Meanwhile, Daphne Rousseau, photo-journalist Dylan Collins and photographer Dimitar Dilkoff struck off to another battered hotspot, Chernigiv, 130 kilometres to the northeast with translator Oleksei Obolenski and driver Pavlo Popovychenko.

On the road they met thousands of vehicles coming the other way, “all with signs on their on windscreens saying, Children.”

They arrived in the city minutes after a volley of heavy shelling. “Everything was still burning fiercely,” Daphne said.

“Buildings were either completely blacked, blown to bits or burning. It is at that moment that we understood that the Russians were not going to do battle with the Ukrainian army. It was going to be about terrorising and levelling cities, emptying them and forcing civilians to run for their lives.

“We went straight to where there had been a strike the night before in which 47 people were killed,” Daphne said. What they found “was just a field of ruins, with a glacial wind whipping through this scene from the apocalypse.”

School damaged by shelling in the city of Chernigiv, on March 4, 2022 (AFP / Dimitar Dilkoff)

School damaged by shelling in the city of Chernigiv, on March 4, 2022 (AFP / Dimitar Dilkoff)

Then “the shelling began again. First it was artillery and then very quickly we heard the noise of two Russian fighter jets. They were flying very, very low, splitting the air, and we knew a new carpet of bombs were about to fall.” A quick decision had to be made, and they sped for the only bridge out of Chernigiv, driving at 120 km an hour. As they got there a bomb fell a few hundred metres away. “We were lucky,” Daphne said.

Fourty-seven people died on March 3, 2022 when Russian forces hit residential areas, including schools in the city of Chernigiv (AFP / Dimitar Dilkoff)

Fourty-seven people died on March 3, 2022 when Russian forces hit residential areas, including schools in the city of Chernigiv (AFP / Dimitar Dilkoff)

Back at headquarters in Paris, several departments were working flat out on the war, from the politics and economics teams to text and image editors, to the agency's diplomatic correspondents and the graphics and multimedia departments, who were turning out maps and explainer articles in several languages.

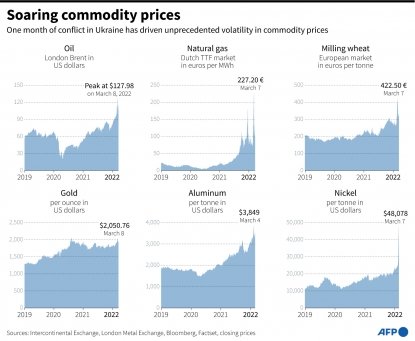

What would the sanctions designed to isolate Russia from the global financial system mean? The implications of closing airspace to Russian aviation were also explored, with other articles asking if Europe could do without Russian gas.

Economic staff in London, who cover a large part of the world's petrol and commodities' markets, ended up pretty much working full-time on the fall-out from Ukraine, said AFP's economics editor-in-chief, Sophie Estienne. “One day they are talking to economists, historians and experts in the geopolitics of agriculture,” she said. “The next we had people working full-time on investigating oligarchs being targeted by the sanctions.”

A Ukraine crisis team made up of journalists across the world who can speak Russian and Ukrainian was set up to back up the reporters on the ground. It helped with “wraps” – AFP jargon for the articles which bring together the day's main developments – or on AFPTV's live feed from Ukraine.

The team also worked closely with fact checkers, tracking and verifying viral images on social media, as well as the claims of the main players like Putin and Zelensky.

A man walks by a destroyed building after a Russian missile attack in Vasylkiv, near Kyiv, on February 27, 2022. (AFP / Dimitar Dilkoff)

A man walks by a destroyed building after a Russian missile attack in Vasylkiv, near Kyiv, on February 27, 2022. (AFP / Dimitar Dilkoff)

A month after the Russian invasion began, the destruction has been immense.

The names of the shattered cities of Kharkiv, Chernigiv and Kherson have become all too familiar. Poor besieged Mariupol – which Human Rights Watch has described as a “freezing hellscape riddled with dead bodies and destroyed buildings” – has joined the roll call of martyred cities alongside Aleppo, Grozny and Guernica.

Kyiv too is unrecognisable. “Life has stopped,” said Daniel Leal. Schools are no longer open and many people no longer go to work.

Firemen working in the rubble of a residential building hit by the debris from a downed rocket in Kyiv on March 17, 2022. (AFP / Fadel Senna)

Firemen working in the rubble of a residential building hit by the debris from a downed rocket in Kyiv on March 17, 2022. (AFP / Fadel Senna)

“We have become used to checkpoints, and to long queues for the few supermarkets and pharmacies that are open,” said Dmytro Gorshkov.

Covering the suffering of his own home town has been hard to bear. But Dmytro has been taken aback by the “extreme solidarity” Ukrainians are showing to each other that helps overcome the circumstances. “Everyone hopes it will not go on too long.”

People wait in line to buy food in front of a supermarket in Kyiv on March 1, 2022. (AFP / Dimitar Dilkoff)

People wait in line to buy food in front of a supermarket in Kyiv on March 1, 2022. (AFP / Dimitar Dilkoff)

War also throws into sharp relief the age-old journalistic dilemma of what responsibility reporters hold for the people they report on.

“An image that stays with me,” said Daphne Rousseau, “is a grandfather I saw carrying a bucket in the middle of the ruins of Chernigiv. He looked completely disoriented. He was preparing his basement for his children and grandchildren who could not get out of the city. They were going to lock themselves in the basement until it all blew over or until death came.

“You have to understand that people get so traumatised they can't leave because they can't manage to organise themselves. We can go back to the hotel at night where we are a lot safer. But we don't know what is left of those people.”

A girl looks out from a window as she waits inside a train taking refugees to Poland at Lviv train station, western Ukraine, on March 5, 2022. (AFP / Daniel Leal)

A girl looks out from a window as she waits inside a train taking refugees to Poland at Lviv train station, western Ukraine, on March 5, 2022. (AFP / Daniel Leal)

The transition to returning home to a country at peace can be tough. Daniel Leal says it takes time to adapt. “You feel slightly lost and sad. I felt deeply disappointed... You feel you haven't done enough, that you could do more, better.”

Dave Clark, who coordinated the AFP teams in Kyiv, felt he had to tell everyone that “I would come back” when he went home. But as coordinator “I felt I had to show an example” by leaving.

Because rotating teams is important, as London-based AFPTV journalist Arman Soldin, who left with Clark, insisted. “I also didn't want to go, but in the car back to Poland I realised just how physically and emotionally tired we were. It is dangerous not to step back.”

Rotating teams also allows people to get psychological support.

Replica of the Statue of Liberty covered with a giant fabric bearing the national colours of Ukraine on March 2, 2022 in Colmar, eastern France (AFP / Sebastien Bozon)

Replica of the Statue of Liberty covered with a giant fabric bearing the national colours of Ukraine on March 2, 2022 in Colmar, eastern France (AFP / Sebastien Bozon)

Olga Shylenko, who has worked for AFP in Kyiv since 2014, is now staying with friends not far from Brussels and also working from there. She feels “terribly guilty” for not having stayed in her homeland.

“I just went to a meeting with other Ukrainian women, and we all said the same thing – we feel really guilty. We have a nice life, we don't live in basements. We would prefer to be there, to participate, but we are mums.”

military checkpoint in the center of Kyiv on March 15, 2022 (AFP / Fadel Senna)

military checkpoint in the center of Kyiv on March 15, 2022 (AFP / Fadel Senna) A desperate inhabitant of Kyiv near a wrapped body after debris of a downed rocket hit a residential building, on March 17, 2022 (AFP / Fadel Senna)

A desperate inhabitant of Kyiv near a wrapped body after debris of a downed rocket hit a residential building, on March 17, 2022 (AFP / Fadel Senna)

At night she has nightmares. “I see myself with my children in Mariupol,” Olga said. Her eight-year-old twins jump when the vacuum cleaner is turned on, thinking it is an air raid siren, and they “are scared by the sound of planes.”

Rescue workers douse the wreckage of a Ukrainian military plane which came down near Kyiv with 14 people on board on February 24, 2022 (AFP / Handout)

Rescue workers douse the wreckage of a Ukrainian military plane which came down near Kyiv with 14 people on board on February 24, 2022 (AFP / Handout)There are no reliable overall death tolls from Ukraine. But casualties have been heavy as reporter Cecile Feuillatre, photographer Bulent Kilic and video journalist Luana Sarmini discovered when they visited the overflowing morgue in the Black Sea port of Mykolaiv. The city has been fiercely resisting the Russian push towards Odessa in the west. Last Saturday they reported on the aftermath of a rocket attack on a military barracks there in which dozens of soldiers died.

The funeral of a woman killed during the bombardment of a cemetery in the southern Ukrainian port of Mykolaiv (AFP / Bulent Kilic)

The funeral of a woman killed during the bombardment of a cemetery in the southern Ukrainian port of Mykolaiv (AFP / Bulent Kilic)

The young man being dragged from the ruins in Bulent's photograph miraculously survived.

A Ukrainian soldier is dragged out alive after being trapped for 30 hours in the ruins of a bombed barracks in the southern port of Mykolaiv on March 19, 2022 (AFP / Bulent Kilic)

A Ukrainian soldier is dragged out alive after being trapped for 30 hours in the ruins of a bombed barracks in the southern port of Mykolaiv on March 19, 2022 (AFP / Bulent Kilic)

In Mariupol alone, authorities estimate 2,000 civilians have been killed. At least five journalists have also died since the war began.

Danger is everywhere in a war, particularly in the first few days when nothing is clear. And the experience of being caught in the fighting is the same for both civilians and journalists, said Daphne Rousseau.

It's like “walking blindfolded into a room with people shooting at you from all directions. You don't know where they are, how far away they are, or what they are firing at you... It could be Grads, the Russian rockets we fear most because they can fall anywhere. Or it might be a Russian commando who is hiding in a thicket somewhere and is just about to shoot.

“It's Russian roulette.”

This post was written thanks in particular to the testimonies of the first teams returning from Ukraine. Thank you to Dave Clark, Sophie Estienne, Dmytro Gorshkov, Antoine Lambroschini, Karim Menasria, Daphné Rousseau, Olga Shylenko, Arman Soldin, Daniel Leal, for their words and to all those who have been or still are on the front line covering this conflict. Interviews by Michaëla Cancela-Kieffer in Paris. English version by Fiachra Gibbons.