Apocalypse now as Australia burns

SYDNEY -- For weeks I’d been dreaming of blue skies and the smell of eucalyptus in the air. I was shivering through one of New Delhi’s coldest winters in a century and one of its worst air pollution seasons in recent years and all I could think about was upcoming Christmas trip home to Australia -- fresh air, soft, sand beaches warmed by the summer sun.

The scene that greeted me was starkly different.

Endless hills of scorched land. Thick trees turned to blackened sticks. Homes reduced into twisted chunks of metal and scattered rubble. A charred kangaroo carcass.

My heart broke into a thousand pieces, but I could not look away. The once lush, green forests that I’d loved to walk and trek through had been turned into a desolate moonscape.

Mount Weison in Blue Mountains, some 120 kilometres northwest of Sydney on December 18, 2019 (AFP / Saeed Khan)

Mount Weison in Blue Mountains, some 120 kilometres northwest of Sydney on December 18, 2019 (AFP / Saeed Khan)I knew something was wrong as soon as I walked out of Sydney’s international airport. The normally azure sky was an unsettling, sullen grey. The city felt subdued. A faint smell of smoke lingered in the air.

Bushfires have long been part of Australia’s fire-prone landscape. And I knew the fires were in full swing before I landed. I’d written about them for more than a decade as a journalist based in the country.

But this summer season was nothing like I’ve seen before. And it took me arriving back in Sydney for that fact to really hit home.

The scale of these bushfires was unprecedented. The corner of the world that I call paradise, my home, was being changed -- possibly forever -- by massive infernos.

Around the town of Nowra in the Australian state of New South Wales, December 31, 2019. (AFP / Saeed Khan)

Around the town of Nowra in the Australian state of New South Wales, December 31, 2019. (AFP / Saeed Khan)They were relentless. Day after day, I saw footage of clear skies turned into an apocalyptic orange or black. Frightened evacuees huddled on beaches as trees were incinerated. Friends and their family were caught up in what became one of Australia's largest peace-time evacuations.

In the heart of Sydney, ash washed up on one of the favourite summer chill-out spots -- Balmoral Beach -- sending veins of black through the yellow sand and transforming the calm waters into a toxic grey soup.

A dog sits amongst ash from bushfires washed up on a beach in Merimbula, in Australia's New South Wales state on January 5, 2020. (AFP / Saeed Khan)

A dog sits amongst ash from bushfires washed up on a beach in Merimbula, in Australia's New South Wales state on January 5, 2020. (AFP / Saeed Khan)Some days, you couldn’t see across Sydney’s famous harbour. On the worst days, people were told to stay indoors rather than go outside and breathe the smoke-filled air.

Residents take a dip to cool down at Lake Jindabyne, under a red sky due to smoke from bushfires, in the town of Jindabyne in New South Wales on January 4, 2020. (AFP / Saeed Khan)

Residents take a dip to cool down at Lake Jindabyne, under a red sky due to smoke from bushfires, in the town of Jindabyne in New South Wales on January 4, 2020. (AFP / Saeed Khan)Almost everyone I spoke to had a family member or friend caught up in the disaster.

I found myself advising people about what anti-pollution masks they could wear. Which air purifiers were effective.

These were little nuggets of knowledge I had picked up in Delhi after moving there to join AFP’s South Asia team in July. Little did I realise that they would come in useful back in Australia -- home to some of the world’s most liveable cities.

Like many of my friends, I also felt helpless. Everyone fretted about the safety of family and friends in the path of the fires, but with road closures cutting them off, there was nothing we could do except monitor the changing conditions, hour by hour.

A demonstrator with a mask attends a climate protest rally in Sydney on December 11, 2019. (AFP / Saeed Khan)

A demonstrator with a mask attends a climate protest rally in Sydney on December 11, 2019. (AFP / Saeed Khan)When AFP asked me to stay and help the bureau with coverage, I didn’t hesitate in saying yes. I felt like I needed to do something to help chronicle what was happening to my country.

A few days later, I headed out with my colleagues to a small town in inland southeastern Australia.

As we drove out of Sydney, it dawned on me that just over a year ago, I had travelled on these same roads for a drought feature.

I had learnt how to shoot video and went on reporting trips with photographer colleagues to document the “big dry”.

The situation was dire. Farmers were hand-feeding their livestock as the pastures were so dry hardly anything could grow in them. Kangaroos were dying because they were hit by cars while trying to eat the tiny strips of grass that sprang up from water running off tarmac after a rare shower.

And here I was, in 2020, documenting the devastating consequences of the drought -- climate-change fuelled bushfires so widespread that we were using the size of countries (Belgium, then Ireland, then Portugal) to give our readers a sense of the scale of the disaster.

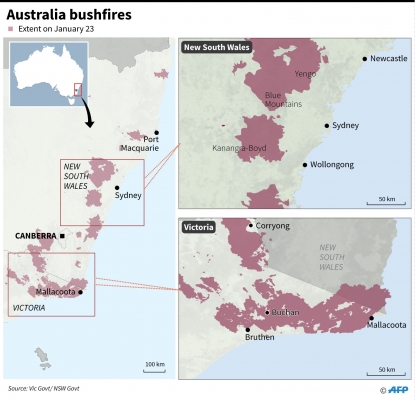

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)A three-year long drought, amplified by climate change, and then fires. A double whammy for already distressed rural folk.

As we neared the small town of Batlow, a small, picturesque town nestled at the foot of the Snowy Mountains and famed for its fruit orchards, the once rolling green hills were now the colour of ash.

I felt like I was in a monochrome painting. The sky was light grey, the air was a hazy white from the smoke, and the ground was black and lifeless. The wind suddenly picked up and I caught myself worrying if it would ignite some scattered smouldering stumps of trees.

Instead of kangaroos lying dead on the side of the highway, I saw the carcasses of kangaroos burnt black beside fences. The claws of one of them was clasped together, like it was making a final prayer before it died. My heart ached. I whispered “sorry” to it, even though I knew it was never going to hear me.

This photo taken on January 8, 2020 shows a dead kangaroo on a farm after bushfires in Batlow, in Australia's New South Wales state. (AFP / Saeed Khan)

This photo taken on January 8, 2020 shows a dead kangaroo on a farm after bushfires in Batlow, in Australia's New South Wales state. (AFP / Saeed Khan)We met several farmers. Two of them had stayed behind to protect their stock. They were shaken by the inferno that swept through but like many rural Australian folk, they were still warm and welcoming.

John Garner, 68, spoke little and often looked into the distance. He saved his cattle but not his neighbour’s, and spent the morning burying the carcasses. Two Kelpies -- Australian cattle dogs -- raced around his feet. “They are my best friends,” he told me.

Cattle graze as the sky turns orange from bushfires in Towamba, 20km from Eden in southern New South Wales on January 10, 2020. (AFP / Peter Parks)

Cattle graze as the sky turns orange from bushfires in Towamba, 20km from Eden in southern New South Wales on January 10, 2020. (AFP / Peter Parks)I wanted to say something comforting, but didn’t know what to say. So I told him I loved kelpies (which I do, they are my favourite dog breed). He got one of them to lift its paw and shake my hand.

Another farmer, Steve Bellchambers, was sitting on a small tractor when we drove past. Beside him was a rifle. He too had been shooting severely injured livestock -- and burying them in pits. As my colleague took photos of his home flattened by the fires, we spoke about life and loss.

"Just because people aren't crying, doesn't mean they are not bleeding inside," he told me.

We came across an orchardist surveying the damage on her land. Stephenie Bailey was still in shock, but agreed to speak to us on camera. “I look like 94 even though I’m 64,” she joked.

64-year-old Stephenie Bailey describes the impact of the bushfires on her farm in Batlow, in Australia's New South Wales state, January 8, 2020.

(AFP / Saeed Khan)

64-year-old Stephenie Bailey describes the impact of the bushfires on her farm in Batlow, in Australia's New South Wales state, January 8, 2020.

(AFP / Saeed Khan)But as she recounted her shock about the strength of the fires and the difficulties she faced evacuating her animals, the emotions welled up inside her.

Owning this orchard was a dream. Her beloved piano was reduced to a pile of ashes and strings. “How will I ever feel truly safe again?," she asked. But in the same breath, like Garner and Bellchambers, she vowed to rebuild her life and home.

As the video interview drew to a close, a tear slowly ran down Bailey’s eye. In that moment, I felt an overwhelming desire to hug her. We instinctively leaned into each other and fell into a deep embrace. It was a long hug. We cried.

Again, I didn’t know what to say, or if I should say anything at all. “Australia is with you,” I said finally. “You are not alone.”

The author and Stephenie Bailey hug as she describes the impact of the bushfires on her orchard farm in Batllow, in Australia's New South Wales state, January 8, 2020. (AFP / Saeed Khan)

The author and Stephenie Bailey hug as she describes the impact of the bushfires on her orchard farm in Batllow, in Australia's New South Wales state, January 8, 2020. (AFP / Saeed Khan)Two days later, I was back in Sydney when the bureau’s news editor emailed. The Sydney Opera House wanted to project a photo of Bailey and me hugging (taken by Sydney’s chief photographer Saeed Khan) as part of a photo tribute to volunteer firefighters. Could I check with Bailey if she was OK with that?

I had only known the day before that the photo of us embracing had been published, and I felt conflicted. It was a private moment. Should it really be projected on the sails of the Opera House? But when I spoke to Bailey, she felt encouraged. It was a chance for her to share with friends messages of hope.

The sails of the Opera House are lit with a series of images to show support for the communities affected by the bushfires and to express the gratitude to the emergency services and volunteers in Sydney on January 11, 2020. (AFP / Saeed Khan)

The sails of the Opera House are lit with a series of images to show support for the communities affected by the bushfires and to express the gratitude to the emergency services and volunteers in Sydney on January 11, 2020. (AFP / Saeed Khan)One of my last stories I covered before I returned to Delhi was the large protests across Australia that called for climate action. Australia’s economy has stayed buoyant over the past three decades largely due to the high demand for fossil fuels and iron, and as a former economics and markets reporter, I wrote regularly about the boom years.

But it seemed to me that this year’s fires served as a wakeup call to many. During the protests, there was anger and frustration in the air. The crowd in Sydney alone numbered some 30,000 -- a large turnout on a Friday night for a protest called at short-notice during the summer holiday season – and there was a wide cross-section of the public, from the elderly to students and parents with their toddlers.

Some were taking part in a rally for the first time. Parents said they were protesting for the sake of their children’s futures. Everyone responded loudly to each speaker’s comments – cheering and booing, and repeatedly calling for the Prime Minister Scott Morrison to step down (“Scomo has got to go”). I’ve covered many rallies over the years, and it’s not often that they are so well-attended and the protesters so energised and eager to be heard.

A car makes its way through thick fog mixed with bushfire smoke in the Ruined Castle area of the Blue Mountains, some 75 kilometres from Sydney, on January 11, 2020. (AFP / Saeed Khan)

A car makes its way through thick fog mixed with bushfire smoke in the Ruined Castle area of the Blue Mountains, some 75 kilometres from Sydney, on January 11, 2020. (AFP / Saeed Khan)It made me think back to the hug, what I had said to Bailey, and why.

This summer, Australia changed. Our landscapes, ecosystems and native animals might never fully recover from the intensity of the blazes. Australia has become the face of climate change -- and its frightening new reality.

A red sky due to smoke from bushfires hang over the town of Jindabyne in New South Wales on January 4, 2020. (AFP / Saeed Khan)

A red sky due to smoke from bushfires hang over the town of Jindabyne in New South Wales on January 4, 2020. (AFP / Saeed Khan)The Australia that I grew up in and know seems to be disappearing. And that hug to me was about sharing the losses that Australians have experienced. And it was also about hope. Hope that as individuals, as families, as a country, we can rise from the ashes.

Editing by Yana Dlugy in Paris.