When the Berlin Wall came tumbling down

Then East Berlin -- A brittle cold gripped the air, and the ink-black sky was dusted with stars. Unlit and pot-holed, the streets of Mitte, the heart of East Berlin, were treacherous to walk on. Ghosts seemed all around me. Blackened buildings still bore the scars of shelling in 1945. A few hundred metres away, the remains of Hitler’s bunker lay entombed in the Death Strip – the no-man’s-land of the Berlin Wall. Everything was grey and menacing, and with the leaden feel of eternity.

Picture taken on April 29, 1984 of the Berlin Wall and the no man's land marking the border between East (Soviet sector) and West Berlin (American sector). (AFP / Joel Robine)

Picture taken on April 29, 1984 of the Berlin Wall and the no man's land marking the border between East (Soviet sector) and West Berlin (American sector). (AFP / Joel Robine)Within hours, all this would change. It was the evening of November 9 1989, and the world was about to be transformed.

The view through a crack in the wall that was made by the "Mauerspeicher" ("wall chiselers") who started hammering at the hated structure shortly after the opening of borders late on November 9, 1989. The grassy mound in the distance is the remains of Hitler's bunker. (Photo courtesy of Richard Ingham)

The view through a crack in the wall that was made by the "Mauerspeicher" ("wall chiselers") who started hammering at the hated structure shortly after the opening of borders late on November 9, 1989. The grassy mound in the distance is the remains of Hitler's bunker. (Photo courtesy of Richard Ingham)But how the event unfolded belies those who argue history is the outcome of titanic forces. Some today see the fall of the Berlin Wall as the inevitable result of Soviet decline. Yet to those who experienced it, the night itself was filled with confusion and danger. Mistakes, individual decisions and sheer luck, far more than the giant hand of history, shaped the outcome.

The Brandenburg Gate is seen through a barbed wire fence, in June 1968. (AFP)

The Brandenburg Gate is seen through a barbed wire fence, in June 1968. (AFP)In those days, AFP had bureaux in East and West Berlin. To cross from one half of the city to the other was a strange and nerve-wracking affair, passing through ‘ghost stations’ on the rail network, crossing through armed checkpoints and braving questioning by the Grenzpolizei, the border police. Our eastern bureau was a vast overheated apartment in Karl-Liebknecht-Strasse, which we presumed was stuffed with microphones, inhabited by our then bureau chief, Charles-Henri Baab.

A bushfire of anger had been spreading to East Germany from the other countries in the Soviet bloc in the east. In October, protests against the ruling SED became bigger and more confident, fanned by then Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s refusal to intervene militarily. I was based in Brussels at the time and was in Berlin, where AFP didn’t have an anglo reporter, to cover the events for the English service. Yet the rallies I saw in early November seemed nowhere near critical mass: the Stasi secret police and their army of informers appeared to have the lid tightly clamped. Even so, behind their monolithic facade, the authorities were on the ropes. Thousands were fleeing West via Hungary, Czechoslovakia and West German embassies in the Soviet bloc. East Germany’s lifeblood was ebbing away.

General view of the Berlin Wall near the Reichstag building, on November 10, 1989. (AFP / Gerard Malie)

General view of the Berlin Wall near the Reichstag building, on November 10, 1989. (AFP / Gerard Malie)On the evening of November 9, Politburo spokesman Guenter Schabowski hosted a press conference, a dreary, jargon-laden daily briefing. After four or five tedious points, Schabowski, patently unprepared, blurted out, “Today, we decided.... er... to introduce a regulation that makes it possible for every citizen of the GDR (German Democratic Republic)... er... to travel via border crossings of the GDR.” Stunned, journalists asked him when this would take place. Schabowski, flustered, fished around in the papers in front of him and stammered, “As I understand it, immediately.”

The word “sofort” (“immediately”) changed history. It transpired much later that the government had scheduled to make the announcement at 4am the following day to give the state apparatus time to prepare. But Schabowski was completely unbriefed -- he had had a piece of paper thrust in his hand at the last minute as he headed to the press conference.

My colleague Luc de Barochez was covering Schabowki’s presser that day and he rushed back to the bureau shortly after the bureau filed an announcement from GDR radio. If memory serves, we filed a bulletin, then the second highest priority, on the easing of travel restrictions. We were cautious about using the highest-priority flash to announce the news: it was unclear whether the Berlin Wall would be fully opened, for Schabowski, reading monotonously from the document, also said travellers would need visas, although these would be issued “at short notice.”

Getting the news out was a nail-biter. By today’s standards, communications were State of the Ark: no internet, no mobile phones, no wi-fi, and the few landlines were reliable only for being monitored. Using a clunky Tandy laptop, you clamped acoustic headphones to the phone handset, wore your fingers out dialling again and again, and prayed the signal would get to Paris.

Picture taken on October 13, 1976 of people looking over the Berlin wall in West Berlin.

(AFP / Ralph Gatti)

Picture taken on October 13, 1976 of people looking over the Berlin wall in West Berlin.

(AFP / Ralph Gatti)With a quick story on the wire, we then decided what to do. Some stayed in the bureau to follow up the story, others headed to the Brandenburg Gate. We had no way of contacting each other, and any copy would have to be phoned from telephone booths to AFP Bonn or Paris, where granny-like stenographers were on 24-hour call.

My choice was Checkpoint Charlie – the East-West crossing point where in 1961, a 16-hour standoff between Soviet and US tanks almost triggered a third world war. I knew that something big was unfolding in Berlin that night, but no idea of just how big. If anything nasty was going to happen, I reasoned, it would be at Charlie. I raced back into the western sector via the Palace of Tears -- the crossing point in Friedrichstrasse that was so named because it was there that East and West Germans would bid each other a tearful farewell. I was nervous. A few days earlier the border police had held me at Friedrichstrasse for questioning and I feared they would detain me again. But to my relief, I just walked through.

Checkpoint Charlie, June 1968. (AFP)

Checkpoint Charlie, June 1968. (AFP)I rushed down to the checkpoint, in the district of Kreuzberg. There, to my surprise, I found no-one there, except for stern-looking American troops in their sentry box. It was eerie: almost nothing seemed to have changed in 28 years. But word began to spread, with West German TV – whose 8pm news was hugely followed in East Berlin – saying that the borders had been flung open. What no-one knew was that the world was about to roll the dice. The border guards – instructed to shoot to “defend” the GDR border without questions -- had been given no instructions about what to do.

In those days, backed onto the Wall, Kreuzberg was rundown and edgy, its graffiti’d buildings a haven for draft-dodgers, anarchists and Turkish guest workers. The space on the western side of the checkpoint quickly filled up as drinking halls emptied. A raucous crowd gathered, and we were soon densely packed – the heat from other bodies providing a useful barrier from the cold, as I had brought only a thin raincoat. The stink of beer and schnapps filled the air, and the swelling mob grew impatient. A chant went up: “Wir wollen Kaffee trinken, am Alexanderplatz” (“We want to drink coffee in Alexanderplatz,” the main square in East Berlin).

We heard shouts from behind the screens on the other side of the checkpoint, perhaps 100 metres away: East Berliners had gathered and were waiting to cross. Yet there was still no sign of movement and a dark rumour spread that truckloads of East German conscripts had been brought up – this was just five months after the Tiananmen Square massacre in Beijing, and weeks after a bloody crackdown on protests in East Berlin. Like an animal, the crowd seemed to react as one -- a chill of fear gripped the mob, which made me afraid of being crushed if a stampede broke out. Just as quickly, that fear turned to booze-fuelled anger, and some in the crowd began to inch towards the border line, demanding that the East Germans be let through. I looked at the faces of the East German border guards facing us as they stared at what must surely have seemed like a hostile crowd creeping towards them. They were pale-faced, terrified, clueless – and trained to kill without thinking. This, I suddenly thought, could go badly.

But then a strange thing happened: a drunken young man on a bicycle appeared in front of the crowd and started doing tricks – cruising in circles and heading teasingly to the border line and swerving comically away at the last moment. It was enough to distract the mob, to raise a smile among the border guards and then a laugh from everyone, and the tension flooded away as quickly and as magically as it had come. And then, at that very moment, the officer on the other side of the checkpoint decided to open the gate, and the river of East Germans came through.

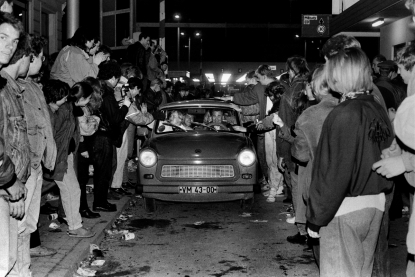

East Berliners are welcomed by the crowd as they enter West-Berlin by car at the Checkpoint Charlie on November 9, 1989. (AFP / Francoise Chaptal)

East Berliners are welcomed by the crowd as they enter West-Berlin by car at the Checkpoint Charlie on November 9, 1989. (AFP / Francoise Chaptal)Their Trabant cars were showered with sparkling wine and flowers, and banknotes were pressed into hands through open windows. Those who came across by foot were hugged and hugged again. The floodgates of tears – for joy – were opened.

West Berliners crowd in front of the Berlin Wall early 11 November 1989 as they watch East German border guards demolishing a section of the wall in order to open a new crossing point between East and West Berlin, near the Potsdamer Square. (AFP / Gerard Malie)

West Berliners crowd in front of the Berlin Wall early 11 November 1989 as they watch East German border guards demolishing a section of the wall in order to open a new crossing point between East and West Berlin, near the Potsdamer Square. (AFP / Gerard Malie) Thousands of East Berliners are packing at one of the new openings created by army bolldozers, at Eberswalderstrasse, in order to enjoy sightseeing and shopping at West, on November 11, 1989. (AFP / Patrick Hertzog)

Thousands of East Berliners are packing at one of the new openings created by army bolldozers, at Eberswalderstrasse, in order to enjoy sightseeing and shopping at West, on November 11, 1989. (AFP / Patrick Hertzog)

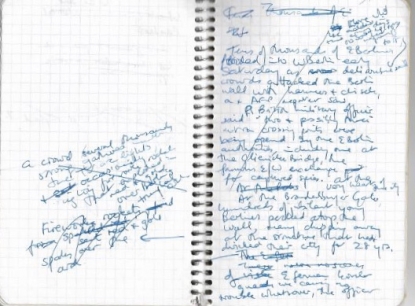

I scribbled it all down furiously into my notepad, got a few quotes and wrote a colour piece that tried to capture the extraordinary scenes I had witnessed. I found a pay phone around the corner, yanked the caller out of it, reversed the charges and dictated my story to Paris, where if I remember it was English Desk stalwart Brian Mair who took the call.

The author's notebook, with notes taken for a story that was filed on November 11, 1989, two days after the wall fell. (Photo courtesy of Richard Ingham)

The author's notebook, with notes taken for a story that was filed on November 11, 1989, two days after the wall fell. (Photo courtesy of Richard Ingham)By midnight, thousands were standing on the Wall, an act for which they would have been shot hours before.

West Berliners sit on the Berlin wall as East-German policemen stand guard on November 10, 1989.

(AFP / Francoise Chaptal)

West Berliners sit on the Berlin wall as East-German policemen stand guard on November 10, 1989.

(AFP / Francoise Chaptal)The following day, the sound that filled Berlin was that of hammer and chisel as citizens pounded at the Wall, destroying it chip by hated chip.

A Berliner holds up a hammer and a chisel early on November 15, 1989 in front of the fallen wall at the Brandenburg Gate. (AFP / Gerard Malie)

A Berliner holds up a hammer and a chisel early on November 15, 1989 in front of the fallen wall at the Brandenburg Gate. (AFP / Gerard Malie)Few journalists have the great luck to see a once-in-a-century event, especially one of joy rather than of death and sorrow. The fall of the Berlin Wall changed the course of world history -- and of my life too. AFP sent me to cover other big events in Eastern Europe and appointed me as the first anglo reporter in Berlin, where I followed German reunification. While there, I met and fell in love with a New Zealand journalist working for The Observer, we went to Hong Kong and we adopted two orphans from Russia: none of this would ever have happened if the Wall hadn’t fallen. So that night, for me, remains a touchstone of personal happiness. But it also reminds me of how individuals can change the course of history – from an apparatchik who makes a botched announcement to an overwhelmed officer at a border post… and a drunken guy on a bike.

The author (in trench coat in front of the white sign), stands in front of the wall in the days following its fall.

(Photo courtesy of Richard Ingham)

The author (in trench coat in front of the white sign), stands in front of the wall in the days following its fall.

(Photo courtesy of Richard Ingham)