Smoke gets in your lungs

Kuala Lampur -- As I looked out of the window of my apartment in the Malaysian capital Kuala Lumpur last month, the skyscrapers on the horizon disappeared behind vast clouds of acrid, yellow-brown smoke. Across town, the Petronas Twin Towers – the city’s best-known landmark -- were being swallowed by an enormous, fast-advancing bank of toxic smog.

Malaysia's capital skyline with landmark Petronas Twin Towers seen in the center is blanketed by haze in Kuala Lumpur on September 18, 2019. (AFP / Sadiq Asyraf)

Malaysia's capital skyline with landmark Petronas Twin Towers seen in the center is blanketed by haze in Kuala Lumpur on September 18, 2019. (AFP / Sadiq Asyraf)My two-year-old son had developed a hacking cough while I and other family members started feeling lethargic and queasy. We quickly closed all the windows and put the air purifiers on at maximum power.

Covering a story is one thing, but finding yourself directly in the middle of it is quite another. Clearly we weren’t as badly affected as others by the smog, but it was still surreal to be writing about all those suffering from it while coughing away at my desk.

This picture taken on September 20, 2019 shows Indonesian women get a doze of oxygen at a special pollution-free centre for residents in the haze covered Pekanbaru, Riau. (AFP / Wahyudi)

This picture taken on September 20, 2019 shows Indonesian women get a doze of oxygen at a special pollution-free centre for residents in the haze covered Pekanbaru, Riau. (AFP / Wahyudi)The smoke engulfing Malaysia and other parts of Southeast Asia came from raging Indonesian forest fires, which are generally started to clear land for agriculture.

They burn out of control annually but get particularly bad every few years when the region suffers a prolonged dry season, leaving tens of millions choking on smelly smoke, closing schools for weeks and producing vast quantities of greenhouses gases.

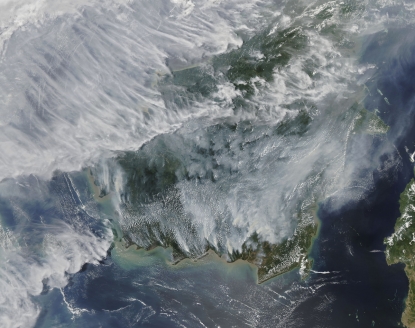

This NASA Observatory Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASAÃs Aqua satellite image obtained September 19, 2019 shows fires burning in peat deposits in Indonesia on September 14, 2019, releasing gases and particles that have consequences for public health and the climate. (AFP / NASA Earth Observatory/Handout)

This NASA Observatory Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASAÃs Aqua satellite image obtained September 19, 2019 shows fires burning in peat deposits in Indonesia on September 14, 2019, releasing gases and particles that have consequences for public health and the climate. (AFP / NASA Earth Observatory/Handout)The climate impact can be almost unbelievable – at the peak of a major outbreak in 2015, Indonesia was spewing out more greenhouse gases than the US, according to an environmental NGO.

The Seri Wawasan bridge (C) is seen covered by haze in Putrajaya on October 23, 2015. (AFP / Mohd Rasfan)

The Seri Wawasan bridge (C) is seen covered by haze in Putrajaya on October 23, 2015. (AFP / Mohd Rasfan)I’ve been in the unique position of covering the fire outbreaks from the source country – Indonesia – and from one of its worst affected neighbours – Malaysia. Each has brought with it two very different experiences.

Indonesia is such a vast country – the world’s biggest archipelago, with over 17,000 islands – that oddly enough Jakarta, and most of the country’s elite, are spared from the smog from the fires, which burn far away from the economic and political heart of the country, Java island.

A Forest and land fire task force officer tries to douse a fire at a palm oil plantation in Pekanbaru, in Riau province, on July 20, 2019. (AFP / Wahyudi)

A Forest and land fire task force officer tries to douse a fire at a palm oil plantation in Pekanbaru, in Riau province, on July 20, 2019. (AFP / Wahyudi)During the two serious fire outbreaks I covered while in Jakarta, I would spend all day writing away about people choking on haze in foreign lands only to find blue skies when I stepped out of the office.

Well, mostly blue – Jakarta suffered from some air pollution due to the vast number of cars on the roads, but it was still nothing compared to the sudden onset of serious air pollution that I experienced in Kuala Lumpur this year.

Indonesia has a famously prickly relationship with its two closest neighbours, Malaysia and Singapore, whose howls of anger about the smog-belching fires are often casually batted away or elicit furious responses in Jakarta.

A passenger aircraft taxis amid thick haze, caused by smog-belching forest fires in Indonesia, at the Sultan Iskandar Muda airport in Aceh province on September 23, 2019. (AFP / Chaideer Mahyuddin)

A passenger aircraft taxis amid thick haze, caused by smog-belching forest fires in Indonesia, at the Sultan Iskandar Muda airport in Aceh province on September 23, 2019. (AFP / Chaideer Mahyuddin)During the first fire outbreak I covered in 2013, an Indonesian minister memorably told Singapore to stop acting “like a child” in response to leaders in the city-state demanding action when air quality dipped to unhealthiest levels on record.

And during one serious haze season, then Indonesian Vice President Jusuf Kalla reportedly reacted with irritation to complaints about the haze, saying the country’s neighbours should be grateful for the clean air that Indonesia usually sends them.

"For 11 months, they enjoyed nice air from Indonesia and they never thanked us,” he grumbled.

Buildings are seen as haze blankets the skyline of Singapore on September 18, 2019. (AFP / Mladen Antonov)

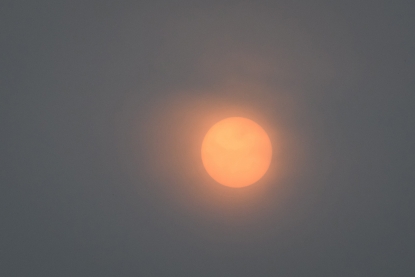

Buildings are seen as haze blankets the skyline of Singapore on September 18, 2019. (AFP / Mladen Antonov) The sun is seen as haze blankets the skyline of Singapore on September 18, 2019. (AFP / Mladen Antonov)

The sun is seen as haze blankets the skyline of Singapore on September 18, 2019. (AFP / Mladen Antonov)

I found such comments amusing at the time – why shouldn’t Jakarta have a bit of fun mocking its neighbours?

Fast forward a couple of years and, having moved to Malaysia with my family, including my young son, the smile has been wiped clean off my face.

Indonesian schoolgirls wear face masks as they are sent home after schools were ordered closed in Pekanbaru, Riau on September 10, 2019. (AFP / Wahyudi)

Indonesian schoolgirls wear face masks as they are sent home after schools were ordered closed in Pekanbaru, Riau on September 10, 2019. (AFP / Wahyudi)We had about a month of solid smog at the peak of the forest fire season, and it has a major impact on daily life, particularly with young kids.

My son had a hacking cough for the whole month, as did all the family.

We were confined indoors most of the time, and had to keep all the windows shut, highly frustrating for a very active two year old who loves running around outside. When I did venture out, I had to wear a mask, my eyes would sting and a pungent smell of burning foliage filled the air.

A picture taken in Kampar, in Sumatra island's Riau province on September 16, 2019 shows smouldering peatland following fire. (AFP / Adek Berry)

A picture taken in Kampar, in Sumatra island's Riau province on September 16, 2019 shows smouldering peatland following fire. (AFP / Adek Berry)Thousands of schools closed across the country at one point when the air quality dipped to “very unhealthy” levels, including around Kuala Lumpur, and reports of respiratory illnesses and other ailments linked to the pollution surged.

Still, what we experienced paled in comparison to the suffering of millions of Indonesians living in the worst-affected areas in the archipelago, on the islands of Sumatra and Borneo.

Indonesian Muslims, most seen wearing pollution masks, gather for special prayers asking for rain in Pekanbaru, Riau province on September 13, 2019, as smog from rainforest fires envelop the Southeast Asian region. (AFP / Adek Berry)

Indonesian Muslims, most seen wearing pollution masks, gather for special prayers asking for rain in Pekanbaru, Riau province on September 13, 2019, as smog from rainforest fires envelop the Southeast Asian region. (AFP / Adek Berry)There, air quality deteriorated to “hazardous” levels and smoke so dense filled the air that in some places it looked continually like dusk for weeks on end. Pictures that went viral from hard-hit Jambi province on Sumatra showed the skies turning an eerie blood red during the day as the haze filled the sky.

This picture taken on August 10, 2019 shows Indonesian firefighters battling a fire at a peatland forest in Ogan Ilir, South Sumatra, due to the dry season which had worsened in recent weeks. (AFP / Abdul Qodir)

This picture taken on August 10, 2019 shows Indonesian firefighters battling a fire at a peatland forest in Ogan Ilir, South Sumatra, due to the dry season which had worsened in recent weeks. (AFP / Abdul Qodir)There is no sign of any long-term solution to the problem, and it will likely reoccur within a few years.

Southeast Asia has been blighted by such pollution outbreaks for over two decades. While regional leaders have made efforts to tackle the issue, regularly holding meetings about the blazes, and signing agreements, nothing has so far had much of an impact.

This picture taken on August 10, 2019 shows Indonesian firefighters battling a fire at a peatland forest in Ogan Ilir, South Sumatra, due to the dry season which had worsened in recent weeks. (AFP / Abdul Qodir)

This picture taken on August 10, 2019 shows Indonesian firefighters battling a fire at a peatland forest in Ogan Ilir, South Sumatra, due to the dry season which had worsened in recent weeks. (AFP / Abdul Qodir)Environmentalists say the Indonesian fires are generally started to quickly and cheaply clear land for highly lucrative industries, such as palm oil and pulpwood used to make paper. As long as there is money to be made from them, the blazes will keep burning.

The skies over Malaysia have cleared for now. My son is back to happily riding around on his tricycle outside, playing with his friends and splashing around in swimming pools.

But we are already looking ahead to next year with dread, knowing that we may face another long period of enforced confinement due to devastating fires in another country.

Indonesian firefighters spray water to help extinguish a fire in Kampar on September 16, 2019. (AFP / Adek Berry)

Indonesian firefighters spray water to help extinguish a fire in Kampar on September 16, 2019. (AFP / Adek Berry)