“Arigato gozaimasu, Brazil”

So what's Japanese for 'How I learned to stop worrying and love Brazil?' Rio de Janeiro correspondent Sebastian Smith looks back on three tumultuous years in Brazil, as he heads to Washington DC to take up his new posting.

Rio de Janeiro -- This is the story of how, in order to grasp what makes Brazilians tick, I first had to learn Japanese. And how in the process I broke a toe, dislocated a finger, sprained most things, bruised the others, made friends, and still ended up with questions about this enchanting, confounding country.

But then things are never simple in Brazil.

First, a word about how I got here.

Taking on a new job as a foreign correspondent is often like a successful version of an arranged marriage.

Your bosses have signed off and the country awaits. The two of you still need to get to know each other, but you've probably got something in common already. For example, you speak the language or maybe you worked there already years ago, or have always been fascinated by the country's culture.

View of the Botafogo cove in the Guanabara Bay with Christ the Redeemer statue atop the Corcovado mountain, at dawn in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on September 4, 2017. (AFP / Apu Gomes)

View of the Botafogo cove in the Guanabara Bay with Christ the Redeemer statue atop the Corcovado mountain, at dawn in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on September 4, 2017. (AFP / Apu Gomes)Then there's also the blind date type of posting. This time, you haven't thought it through much. You're enticed by the few details available. Prepared or not, you walk in, heart beating, and try to match the description to reality.

My transfer to Rio de Janeiro in 2015, after years with AFP in the US, Europe and Russia, was the second kind.

Neither I nor my family had set foot in Brazil and most of my impressions of the place were formed from movies or memories of the yellow-shirted football team alternately beating everyone and collapsing in tears. The only thing I could predict accurately was that I would never convincingly dance the samba.

But there are times as a journalist when being a blank slate is a good thing.

Diving in. A young man jumps into the sea at Boa Viagem beach in Salvador, Bahía, Brazil, on January 1, 2015. (AFP / Yasuyoshi Chiba)

Diving in. A young man jumps into the sea at Boa Viagem beach in Salvador, Bahía, Brazil, on January 1, 2015. (AFP / Yasuyoshi Chiba)In 2015, Brazil's entire political class was plunging into a corruption crisis dubbed "Operation Car Wash," Rio was one year from hosting South America's first-ever Olympics, and I was going to scribble all over that slate.

Some days the scene viewed from AFP in Brazil resembled the fabled Latin American soap opera. Some days it was more of a bad dream sequence.

President Dilma Rousseff's brutal 2016 impeachment; the economy turning to what investors charmingly term "junk;" carnival; "Car Wash;" Zika; drug wars; bittersweet preparations for an Olympics that everyone knew would fuel ghastly corruption…

The stories kept coming, merging, like the one about fears over Zika-carrying mosquitoes feasting on naked flesh at carnival time, or Rousseff's even more unpopular replacement Michel Temer getting booed at the Olympics opening ceremony.

Getting on top of current events, though, is only the start of a journalist's relationship with a country.

I wanted something deeper.

Children play with water at the Madureira park in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on January 25, 2015. (AFP / Yasuyoshi Chiba)

Children play with water at the Madureira park in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on January 25, 2015. (AFP / Yasuyoshi Chiba)And so it was that I found myself walking up the steep staircase to a judo club one evening.

I didn't know anything about judo -- even less than I knew about Brazil -- but the club was right around the corner from my apartment. Whenever I came home from work I'd see people in white or blue whirling past the windows. I was intrigued.

It occurred to me that a sport with a bit of rough and tumble might be an apt metaphor for life in the continent's biggest country. Also, as I soon established, there were no other gringos in the club. It's too easy as a foreigner to hang out mostly with other expats. And as a journalist it's too easy to rely on the opinions of the professional analysts we quote in stories all the time. I wanted to get real.

At the Judo Clube Oswaldo Simoes -- a tiny place with a blue tatame, the traditional portrait of the sport's founder Jigoro Kano, and netting over the windows -- my education was about to begin.

One thing I was looking forward to was improving my Portuguese. In such a purely Brazilian setting and at the JCOS, as the club is called for short, I’d have no shortage of language-learning partners.

The only problem is that if you find grammar and pronunciation tricky at normal times, then try it when your interlocutor is throttling you or hurling you across the room. That strong netting over the windows, it emerged, was to keep people in the dojo.

The author (on the ground) takes a tumble during his judo class in Rio de Janeiro, August 29, 2018. (AFP / Carl De Souza)

The author (on the ground) takes a tumble during his judo class in Rio de Janeiro, August 29, 2018. (AFP / Carl De Souza)Plus I discovered another snag in my linguistic voyage: I was going to have to learn Japanese.

OK, I was only learning judo vocabulary, not actually to speak Japanese, but when words like koshi, kuzuri, kumikata and kansetsu are part of your after-work chatter, you know you're not in Kansas anymore.

I mean, even getting my sparring partners' names straight wasn’t always easy.

Brazilians have a mania for nicknames and abbreviations, like calling ex-president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva just "Lula," even if his actual surname is da Silva.

At the JCOS, people's names were inscribed on their belt, but this was often of no help.

The author's judo belt. (AFP / Carl De Souza)

The author's judo belt. (AFP / Carl De Souza)Take Leo, a huge guy. That was easy enough. But then his son came and he was also called Leo, except that because he was even huger than his father, he was commonly known as Big Leo or plain “Big” – yes, in English and pronounced Beeg.

A judoka referred to as Ze was really Jose Carlos. His son, a strapping teenager, also had a name but I never knew it, because to everyone he was Toddy Riner. That's Riner in homage to France's heavyweight judo deity Teddy Riner and Toddy in reference to the boy's love of chocolate milk drinks sold in Brazil under the name Toddy. Got it? We called him Toddy for short.

Me? I was "o gringo," which has no really pejorative connotation in Brazil. It just means you're from abroad.

But, bit by bit, I wasn’t quite as much of a gringo as I used to be.

I was starting to throw people. It wasn’t always me who got choked. I was building up my Portuguese and even grasping the Japanese lexicon. And, most importantly, I was getting a chance to see Brazilians in a non-work-related light -- to see them as they see themselves.

Brazilian gymnast Virginia Lins does a handstand on Ipanema Beach in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on June 1, 2018. (AFP / Carl De Souza)

Brazilian gymnast Virginia Lins does a handstand on Ipanema Beach in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on June 1, 2018. (AFP / Carl De Souza)So after three years on the mat with Oswaldo and his JCOS team, and on the eve of my departure from Latin America's biggest country to North America's biggest country, here are a few takeaways:

Entering the JCOS meant a true Brazilian rite of passage: joining my first-ever WhatsApp chat group.

The messaging app has astonishing penetration in Brazilian society. Almost anyone with a cellphone in this nation of 209 million relies on WhatsApp for calls and messaging communication.

The daily stream of group messages gave me a window on the Brazilians' world-class talent for memes, their diligent sharing of YouTube videos, and their epic exchanges of emoticon-filled jokes where -- oddly to a gringo at first -- it turns out that "KKK" means LOL.

Proven fact: put two or more Brazilians together on WhatsApp and the LOLs will flow.

Musicians play samba music, as they do every Monday, at Salt Stone Square (Pedra do Sol) near Rio de Janeiro's port, November 12, 2012. (AFP / Christophe Simon)

Musicians play samba music, as they do every Monday, at Salt Stone Square (Pedra do Sol) near Rio de Janeiro's port, November 12, 2012. (AFP / Christophe Simon)Not true, but still… I was astonished at how many of the folk rolling around that tatame in the evenings spent their days in a suit wrestling with legal matters. Turns out, I needn't have been surprised: Brazil has more than a million lawyers, putting it among the top per capita rankings worldwide. Lots of lawyers and slow, inefficient justice is one of the country's defining characteristics.

The JCOS is located in relatively swish Copacabana and quite a few of its members -- though far from all -- belong to Brazil's reasonably well-off middle class. But as the steady trickle of stray bullet deaths and injuries around Rio attests, there's nowhere really safe in a city where criminals are often stronger than the cops and the cops can be just as violent as the gangsters. In the middle of training we'd hear shouting or other signs of a fight or trouble outside, always bringing several judokas to the window.

Many club members lived far away, driving long distances across the city, and our WhatsApp group would light up with hair-raising warnings about shootouts or police raids shutting down main highways.

A policeman aims his assault rifle at the entrance of the Alemao favela, north of Rio de Janeiro, June 27, 2007.

(AFP / Antonio Scorza)

A policeman aims his assault rifle at the entrance of the Alemao favela, north of Rio de Janeiro, June 27, 2007.

(AFP / Antonio Scorza)Like so many Cariocas, as Rio residents are called, the JCOS members never stopped ribbing each other, laughing or talking loudly. Cariocas don’t do shy and retiring.

"Typical lawyers," sensei would grumble, usually while trying to repress his own laughter. But tellingly, there was one major subject off limits in all the banter: politics.

These are tense days in Brazil ahead of October presidential elections.

The most popular politician is Lula, despite being locked up for corruption. The next most popular is a right-wing ex-army captain called Jair Bolsonaro who thinks the 1964-85 dictatorship was a pretty good thing. The result of this election will impact on the destiny of tens of millions of people, but discussing the options among friends is clearly too painful.

"Just judo," someone would quickly remind whenever the unwritten rule was broken on WhatsApp.

Actually, there was one further topic considered too explosive to broach at the JCOS: club football.

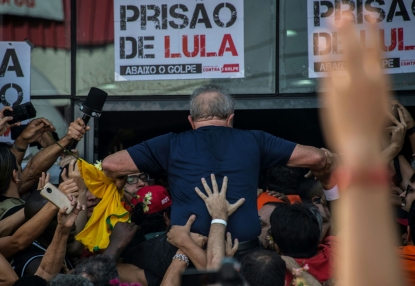

Brazilian ex-president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva is carried by supporters after attending a Catholic Mass in memory of his late wife in Sao Bernardo do Campo, in Sao Paulo, Brazil, April 7, 2018. (AFP / Nelson Almeida)

Brazilian ex-president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva is carried by supporters after attending a Catholic Mass in memory of his late wife in Sao Bernardo do Campo, in Sao Paulo, Brazil, April 7, 2018. (AFP / Nelson Almeida)Special training sessions, say with an invited big name athlete, often begin with the national anthem in Rio. Brazilians are endearingly proud of their nation, without the aggressiveness of nationalism.

But, again, these are difficult times. In Sensei Oswaldo, who represented Brazil at the Moscow Olympics and in countless other international contests, I detected real despair at the corruption and crime poisoning the country he loves.

This explains the growing reports of Brazilians seeking to emigrate or obtain dual nationality. One fellow judoka student returned from vacation in Japan gobsmacked at how orderly the place was. "I really didn't want to come back," he said mournfully.

Another judoka is about to take his family to Germany. What price can you put on having a safe environment to bring up your toddler son, far from Rio's automatic weapon shootouts?

Residents flee during a police raid in the Morro do Alermao favela in Rio de Janeiro, November 28, 2010. (AFP / Jefferson Bernardes)

Residents flee during a police raid in the Morro do Alermao favela in Rio de Janeiro, November 28, 2010. (AFP / Jefferson Bernardes)We've all seen the footage of Brazil's football stars in tears over the years, from joy and sorrow alike. And anyone who exchanges emails or phone calls with Brazilians, even in many professional settings, quickly experiences the disarmingly casual "hugs and kisses" version of our stiff English "all the best."

The author and his judo Sensei Oswaldo hug each other, a regular practice at the judo center.

(AFP / Carl De Souza)

The author and his judo Sensei Oswaldo hug each other, a regular practice at the judo center.

(AFP / Carl De Souza)At the JCOS, Sensei Oswaldo greets students with real hugs and sometimes even a kiss on the head. That's right before he teaches them to flip each other through the air. Brazilian society is often macho, but the tenderness is real and it's infectious. It's one of those details that makes life in a difficult place a little easier.

One time, the whole club secretly raised money to send sensei to Miami to compete in the world tournament for veteran judokas. As someone who earns only a modest amount, he'd never have had the opportunity for such an expensive trip. (The old warrior went on to win a bronze medal at the event.)

On the night the secret was unveiled, the sensei's students, all wearing specially printed T-shirts, poured into the dojo. They sang "The champion is back," a football chant. They made speeches. Sensei wiped away tears. Then everyone went to the bar to celebrate.

Pure Brazil at its joyous, spontaneous, generous best.

Sometimes Brazil seems so submerged in economic, social, environmental, criminal and corruption problems that you wonder if it can ever climb out.

During my many hours at the JCOS and the occasional big training sessions on weekends where we joined judokas from other clubs, I couldn't help thinking that if Brazil lived more by the values of judo it might have a better chance.

A youngster flies a kite at the Vidigal favela in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil on May 18, 2018. (AFP / Carl De Souza)

A youngster flies a kite at the Vidigal favela in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil on May 18, 2018. (AFP / Carl De Souza)OK, there's no guarantee. Russia's Vladimir Putin is a lifelong judoka and many accuse him of human rights abuses and corruption that would make the most scandal-ridden Brazilian blush.

But judo has helped many to order their lives here.

Look at Rafaela Silva, the black judoka who grew up in a dangerous Rio favela. She not only won the nation’s heart when she took gold at the Rio Games, but used her high profile to put down the racists – in a country riven by racism – who branded her a monkey after she was disqualified during the London Games four years earlier.

Few black Brazilians get a chance to answer their abusers like that. She fought for them all.

Brazilian judoka Rafaela Silva, wearing the gold medal that she won at the Rio 2016 Olympic Games, waves during a parade in the Cidade de Deus favela where she was born, August 22, 2016.

(AFP / Yasuyoshi Chiba)

Brazilian judoka Rafaela Silva, wearing the gold medal that she won at the Rio 2016 Olympic Games, waves during a parade in the Cidade de Deus favela where she was born, August 22, 2016.

(AFP / Yasuyoshi Chiba)Another Olympic judo medalist, Flavio Canto, came from the opposite end of society – a golden boy with a nuclear physicist father. But he has put his fame and talent to building one of Brazil’s most successful sports charities, the Instituto Reação, which gives judo training to many of Rio’s poorest kids. Among his alumni? Rafaela Silva.

A person climbs the mountainside of Rio de Janeiro's Sugar Loaf on August 23, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)

A person climbs the mountainside of Rio de Janeiro's Sugar Loaf on August 23, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)Every judoka, from white belt onwards, is taught respect, helping others, striving for perfection, patience, and toughness without viciousness.

Imagine if the likes of President Michel Temer and most of Congress, the leaders of urban death squads, the cynical drug kingpins, corrupt police and the officials who steal while letting public services go to ruin could learn the same lessons?

On the judo mat, blacks and whites are truly equal. They fight and suffer equally. They bow to each other as equals.

Imagine if those values could spread through a country which may be about to elect Bolsonaro, a man mocking the idea that Brazil should repent its past as the world’s biggest importer of African slaves. Brazil could use some judo-style racial harmony.

In judo, humility and simplicity are core principles.

Imagine if they could be passed on to the elites in their high-walled Rio and Sao Paulo villas, as they look down on the truly humble, simple people searching through the garbage below?

View of the upscale neighborhood where Brazilian football star Neymar has a luxury villa, Mangaratiba, Rio de Janeiro, March 4, 2018.

(AFP / Mauro Pimentel)

View of the upscale neighborhood where Brazilian football star Neymar has a luxury villa, Mangaratiba, Rio de Janeiro, March 4, 2018.

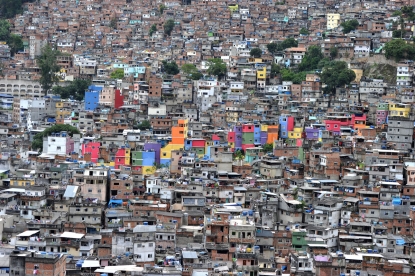

(AFP / Mauro Pimentel) View of the Rocinha favela in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil on December 6, 2011. (AFP / Christophe Simon)

View of the Rocinha favela in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil on December 6, 2011. (AFP / Christophe Simon)

Brazil, you have so much to fight for. But what I saw at the JCOS is that you also have so much strength.

I wish you many, many “ippons,” as the Japanese say for a match-winning judo point. “Duomo arigato gozaimasu” – thank you – for the memories.

And I hope your tears will be far more often for joy than from sadness.

A Brazilian man plays football in Porto Seguro on June 28, 2014, during the Brazil-hosted 2014 FIFA World Cup.

(AFP / Anne-christine Poujoulat)

A Brazilian man plays football in Porto Seguro on June 28, 2014, during the Brazil-hosted 2014 FIFA World Cup.

(AFP / Anne-christine Poujoulat)