Travels through the Arab Spring

TUNIS -- For so long, he was omnipresent, his face, framed by impeccably-coiffed, jet-black hair adorning all the front pages. On public television, you saw images of crowds chanting his name. If we dared to speak of politics in a cafe, we would whisper, so as not to attract unwanted attention. If you wanted to work freely as a reporter, you had to go abroad.

Those days seem so long ago today, seven years after Zine El Abidine Ben Ali was overthrown in a peaceful popular uprising in Tunisia that sparked the Arab Spring. Seven years. Hard to imagine it’s been that long.

On January 14 of this year I found myself along with hundreds of other Tunisians strolling along Bourguiba Avenue, as they have each year since 2011, to mark the day that Ben Ali was ousted after a 23-year iron-fisted reign.

Tunisians mark seven years since their uprising launched the Arab Spring. Bourguiba Avenue, Tunis, January 14, 2018.

(AFP / Fethi Belaid)

Tunisians mark seven years since their uprising launched the Arab Spring. Bourguiba Avenue, Tunis, January 14, 2018.

(AFP / Fethi Belaid)Like every year, the atmosphere is a mix of joy and protests. Like every year, the scene takes me back. The seven years that have passed are a blur of moments of both grace, hope, atrocities and despair. Some dreams and hopes have come true, some have been dashed. But I can’t help but be grateful for the Tunisian revolt that started it all, that transformed the nation and allowed me to return to my home country to work as a journalist without fear and in total freedom.

The Tunisian revolution began in December 2010, sparked by the self-immolation of a vegetable vendor who was distraught after police confiscated his cart and produce in a small town of Sidi Bouzid, some 250 kilometers south of the capital Tunis.

His suicide sparked what eventually turned into mass protests that fed on deep discontent after years of unemployment, inflation, corruption and lack of political freedoms in the country under Ben Ali’s rule. In January, Ben Ali fled, the first dictator to fall in what eventually would become known as the Arab Spring revolts.

Zine Al Abidine Ben Ali in Tunis, November 16, 2005.

(AFP / Eric Feferberg)

Zine Al Abidine Ben Ali in Tunis, November 16, 2005.

(AFP / Eric Feferberg)But while thousands of my compatriots were demonstrating in Tunisia, I was on assignment in Sudan, helping cover the referendum that would eventually give birth to South Sudan. It was my second reporting trip to Sudan and I loved the story, but I was desperate over not being able to cover the unrest at home. I obsessively followed what was happening on the news.

On January 14, 2011, I was reporting on young Sudanese poets, when I get a call. “Ben Ali has gone! He has left Tunisia!” a colleague screamed on the other end of the line. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. I was thrilled, but at the same time worried -- now that the long-time dictator was gone, what and who would take his place? What was going to happen to the country?

I had to return home, I wanted to be in my country at a time like this. Luckily, my bosses understood and allowed me to leave Sudan earlier than scheduled. I got to Tunisia three days after Ben Ali left. Like many of my compatriots, I was both euphoric and incredulous.

My family met me at the airport and we headed straight to Bourguiba Avenue. The streets were nearly empty except for soldiers. After more than two decades of living in a police state, their presence was almost reassuring now that the dictator had gone and no-one knew who or what would replace him. The day was sunny and crisp and there was a whiff of freedom in the air. People driving by saluted the soldiers in the street. Some yelled “Thank you!” toward them.

Protesters kiss soldiers in Tunis, January 20, 2011.

(AFP / Martin Bureau)

Protesters kiss soldiers in Tunis, January 20, 2011.

(AFP / Martin Bureau)My first days back in Tunisia were spent with a permanent smile on my face. It was such a joy to see my country, where people were afraid to discuss politics in public for so long, being transformed into a noisy town square where everyone was talking about anything and everything political all day long. In the open. Not afraid.

After a few days, AFP asked me to stay another week to help with coverage. I'm thrilled. I spent the next few days, from morning until the night-time curfew, with the thousands of protesters who were camped out in the Kasbah, the seat of government, demanding the departure of the transitional government.

It was during this sit-in that it I realized that sometimes journalism is a question of chance.

One day, as I walked along the Bab Bnet Avenue toward government headquarters, I suddenly became aware of a strange commotion to my right, where a crowd had gathered. I hesitated whether to go check it out or not, since gatherings were nothing new. But then I saw a vehicle with a military plate, which intrigued me, so I forced my way through the crowd.

When I got to the middle of the gathering, I found myself next to the army chief of staff, Rachid Ammar. At the time, he was extremely popular, with rumors flying around (never confirmed) that he had refused to fire on demonstrators. I couldn’t believe my eyes -- this man hadn’t said a word in public since Ben Ali’s ouster and there he was, a few centimeters away from me. I got really nervous (what if wasn’t him and I put out a wrong quote?), so I took a picture of his badge and questioned an officer nearby: “It’s really him? It’s really Rachid Ammar?” The officer nodded.

Tunisian army Chief of Staff, General Rachid Ammar, addresses a crowd in central Tunis on January 24, 2011. (AFP / Ines Bel Aiba)

Tunisian army Chief of Staff, General Rachid Ammar, addresses a crowd in central Tunis on January 24, 2011. (AFP / Ines Bel Aiba)After a few minutes, Ammar began to speak. I began to furiously take notes. As soon as he was done, I backed out of the crowd to call the bureau with alerts. “We are faithful to the constitution of the country. We will defend the constitution. We will not overstep its boundaries.” I was so caught up in the moment that I didn’t realize until later that evening, after a colleague told me, that I had got a huge “scoop.”

As much as I loved covering the changes roiling my home country, I couldn’t stay there forever. I had been posted to Egypt for the past four years, where protests were also starting. I headed back to Cairo.

Seventh day of demonstrations on Tahrir Square, January 31, 2011.

(AFP / Marco Longari)

Seventh day of demonstrations on Tahrir Square, January 31, 2011.

(AFP / Marco Longari)I went to the bureau directly from the airport. It was a day after Friday January 29, when numerous people were killed by police during protests.

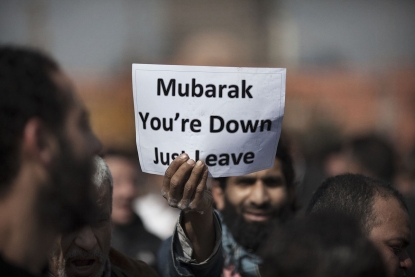

The roads were nearly deserted. The building housing the headquarters of President Hosni Mubarak’s party, not far from Tahrir Square, was smoking, having been set alight by protesters the day before.

An effigy of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak hangs over Cairo's Tahrir Square on February 1, 2011, ten days before his resignation.

(AFP / Patrick Baz)

An effigy of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak hangs over Cairo's Tahrir Square on February 1, 2011, ten days before his resignation.

(AFP / Patrick Baz)I was so happy to be back among my colleagues, especially Jailan Zayan, my “sister from another mother.” The bureau was a busy beehive, with correspondents having arrived from the world over to help with coverage. It marked the start of crazy weeks of non-stop work.

We spent most of our days and many of our nights between the bureau and Tahrir Square, the epicenter of the Egyptian revolution. We often slept at a nearby hotel, so as not to have to go home during curfew.

Surreal scenes would jump out from the general blur of chaos that marked those days.

Like one day, when Mubarak supporters riding horses and camels attacked protesters in Tahrir.

Supporters of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, on horses and on a camel, clash with anti-regime protesters in Cairo on February 2, 2011. (AFP / Andrey Smirnov)

Supporters of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, on horses and on a camel, clash with anti-regime protesters in Cairo on February 2, 2011. (AFP / Andrey Smirnov)The Egyptians’ humor was legendary and we often found ourselves laughing at the revolutionaries’ slogans. They even found something funny in the announcement that Mubarak was stepping down, made by his feared intelligence chief Omar Suleiman, honing in on a man standing in utmost attention behind him as he made the historic declaration. “The man behind Omar Suleiman” became such a sensation, replete with his own Facebook page, that his family at one point appealed to people to stop the jeering.

The home of the Egyptian revolution was undoubtedly Tahrir Square, the symbol of all the hopes embodied in the protests. But Tahrir had a dark side, the scene of numerous assaults on women. One evening, I was in the square covering the appearance of opposition leader Mohamed el Baradei. I was less than a meter away from him, when I felt hands on my body, trying to take off my sweater. The crowd was so dense that I couldn’t tell who the culprit, or culprits, were. I had to scream at the top of my lungs to get myself out of there. It was just one of many such ugly incidents that I and my female colleagues had to live through as we went about doing our job.

Tahrir Square, Cairo, February 1, 2011.

(AFP / Mohammed Abed)

Tahrir Square, Cairo, February 1, 2011.

(AFP / Mohammed Abed)Despite the difficulties, we were all on a high, knowing that we were witnessing History. Especially for Jailan and me -- I was a Tunisian living in Cairo, she was the daughter of a Libyan opposition activist forced into exile by Moamer Kadhafi. So when the Arab Spring storm reached Libya, it only added a notch to the emotional roller coaster that we had been riding for months.

A Libyan rebel stands on a picture of Libyan leader Moamer Kadhafi in the rebel stronghold of Benghazi on June 22, 2011.

(AFP / Patrick Baz)

A Libyan rebel stands on a picture of Libyan leader Moamer Kadhafi in the rebel stronghold of Benghazi on June 22, 2011.

(AFP / Patrick Baz)Between 2011 and 2012, I spent nearly four months in Libya.

The first time I went was in September 2011, arriving in Benghazi. It was a magical time. Everything was open, extraordinarily so, a journalist’s dream. One day I attended a meeting of army officers. It was supposed to be closed, but “the journalist can stay,” one of them said. The officers then went on to proclaim Khalifa Haftar as the head of the Libyan National Army. We interviewed Haftar weeks later at a secret location in Tripoli. We were driven there without knowing where we were going. I felt like I was in a spy movie.

In hindsight, all the ills that would befall the country in a few months, the tensions between the various militias, were already there in those heady first days of freedom. Even back then, we suspected that the transition from years of Khadafi dictatorship to democracy would be turbulent. But we also allowed ourselves to be carried away by the hopes of the Libyans, who found themselves free to speak after 42 years of a vicious dictatorship.

Libyan rebels ready their weapons and munitions in Ajdabiya on March 2, 2011 as pro Moamer Kadhafi soldiers and mercenaries armed with tanks and heavy artillery stormed the nearby city of Brega. (AFP / Marco Longari)

Libyan rebels ready their weapons and munitions in Ajdabiya on March 2, 2011 as pro Moamer Kadhafi soldiers and mercenaries armed with tanks and heavy artillery stormed the nearby city of Brega. (AFP / Marco Longari)In between covering the revolution, I got a chance to visit some breathtaking archaeological sites during my time there, like the magestic Leptis Magna, which I dreamed of seeing as a child.

The Libyan experience marked me for a long time. I had a CD of Libyan revolutionary songs, which I knew by heart and which I made my poor friends listen to over and over again. I can rarely bring myself to listen to them anymore -- the music that used to lift my spirits in hope now leaves a bitter aftertaste as I think of the horrible situation that the country finds itself in.

A Libyan rebel poses with weapons after fierce fighting erupted afresh around the battleground Libyan crossroads town of Ajdabiya, on April 14, 2011. (AFP / Odd Andersen)

A Libyan rebel poses with weapons after fierce fighting erupted afresh around the battleground Libyan crossroads town of Ajdabiya, on April 14, 2011. (AFP / Odd Andersen)After my Libyan adventures I got back to Egypt, but the pull of the homeland was too strong and I returned to Tunisia in the summer of 2013 -- first for a sabbatical and then, from 2014, as the deputy bureau chief of the AFP bureau there. Champagne!

The first months back home were magical. Just the fact of working in central Tunis, a neighborhood that I have always loved, filled me with joy. I savored working in my mother tongue (Egyptian Arabic is quite different from Tunisian Arabic). I loved the fact that I could get in touch with anyone, that you could write about anything, without worrying about censorship.

But reality caught up with Tunisia as well. Already, in February 2013, the assassination of opposition activist Chokri Belaid sent a shockwave through the country. Then in July of that year, the same thing happened with an MP, Mohamed Brahmi.

I learned of Brahmi’s death in the most unexpected way. A friend and I were leaving a store on Bourguiba Avenue when we heard a blood-curdling scream. It turned out to be the widow of Chokri Belaid who happened to have been a few meters away from us. She had just learned that Brahmi was killed the same way that her husband -- shot in front of his house by men on motorcycles.

Basma Khalfaoui Belaid (C), the wife of assassinated Tunisian opposition leader and outspoken government critic Chokri Belaid, on February 6, 2013.

(AFP / Fethi Belaid)

Basma Khalfaoui Belaid (C), the wife of assassinated Tunisian opposition leader and outspoken government critic Chokri Belaid, on February 6, 2013.

(AFP / Fethi Belaid)Two days later, we went to Brahmi’s funeral. As with Belaid’s, numerous women attended, breaking with Muslim tradition that only the men accompany the deceased to their final resting place. Returning from the funeral, we saw another taboo being broken -- it was the Muslim holy fasting month of Ramadan, but it was super hot and people stopped at stores to buy bottles of water and juice that they would drink out in the open.

Tunisia settled into an uneasy rhythm -- moments of immense hope, broken up by despair. News that a human rights activist in Egypt had been forbidden from travelling abroad, that two Tunisian journalists had been killed in Libya.

On the one hand, Tunisia held free and open elections for the first time in its history. On the other, it was shaken by bloody attacks, like the one on tourists on a beach in June, 2015, or when a young shepherd accused of collaborating with security forces was killed, his head brought to his mother in a plastic bag. Youth who openly fight against police brutality and for social justice and against homophobia. But also youth who have lost all hope of a better life in their country, many of whom drowned as they take to the seas in the hopes of reaching a better life in Europe. A veritable emotional roller coaster from which I have yet to get off.

A participant in an anti-terrorism rally in Tunis, February 21, 2015. (AFP / Fethi Belaid)

A participant in an anti-terrorism rally in Tunis, February 21, 2015. (AFP / Fethi Belaid)But on January 14, 2018, as I took a coffee break at a cafe on Bourguiba Avenue, I took stock of everything that the country had been through and my optimism remained. I was about to leave for a posting in the United States. So I thought about everything that I had witnessed over the past seven years. Yes, the country was unstable. Yes, the ills unleashed by the revolution were still there -- a demonstrator had died just a few days earlier in unclear circumstances.

Few things irritate me more than when people tell me to be happy because Egypt and Libya are in a much worse situation. But as I left Tunisia, I was at peace and my heart was still full of hope. Because we still have a chance. Despite all that has happened, we still have a chance.

Tunisian youths attend the closing of the second edition of Comic Con Tunisia on July 9, 2017.

(AFP / Fethi Belaid)

Tunisian youths attend the closing of the second edition of Comic Con Tunisia on July 9, 2017.

(AFP / Fethi Belaid)