Name to a number

Chicago, USA -- The project took a bit of time to ripen into what it eventually became -- putting a name to the hundreds of people who are murdered in Chicago every year. But the idea first took hold from the shock that I got when I first arrived in the Windy City six years ago.

When I first landed, I began to follow the shootings and the murders, like any news photographer would. One day I heard that 20 people had been shot, so I called my editor to see if he wanted me to cover it somehow. “20 shot? That’s not news. If 20 killed, yes, but shot? No,” he said. I was blown away. Some of the locals had become so complacent about the violence that it was accepted as just part of life here.

When I talked to people about it, the reaction I got was, “oh, another day in Chicago.” The apathy was shocking to me. It was like they were talking about the weather.

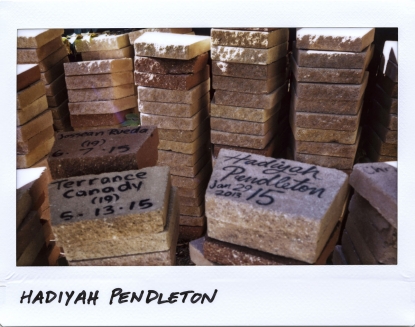

A brick with the name of Hadiyah Pendleton, 15-year-old, is seen stacked up with the bricks for other victims of violence at the Kids Off the Block Memorial in the 11600 block of South Michigan Avenue in Chicago, Illinois on October 9, 2017.

Pendleton, a majorette, who performed at U.S. President Barack Obama's second inauguration, was shot in the back in the 4500 block of South Oakenwald Avenue on January 29, 2013. Two alleged gang member have been arrested and charged with her murder.

(AFP / Jim Young)

A brick with the name of Hadiyah Pendleton, 15-year-old, is seen stacked up with the bricks for other victims of violence at the Kids Off the Block Memorial in the 11600 block of South Michigan Avenue in Chicago, Illinois on October 9, 2017.

Pendleton, a majorette, who performed at U.S. President Barack Obama's second inauguration, was shot in the back in the 4500 block of South Oakenwald Avenue on January 29, 2013. Two alleged gang member have been arrested and charged with her murder.

(AFP / Jim Young)Of course I knew before I got here that there was crime and violence in the city -- crime in Chicago has been going on since there has been a Chicago. But I wasn’t prepared for the complacency that I encountered at times.

And that lay in the heart of the project for me -- to shake up the complacency, to give the victims of the violence a name and to leave a trace of what had happened to them.

Chicago at the moment has the undistinguished reputation of being America’s deadliest city. This year, more than 620 have been murdered, according to stats compiled by the Chicago Tribune newspaper. That’s nearly twice as many people killed in the city of 2.7 million than in New York City and Los Angeles (the two largest cities in the US), combined.

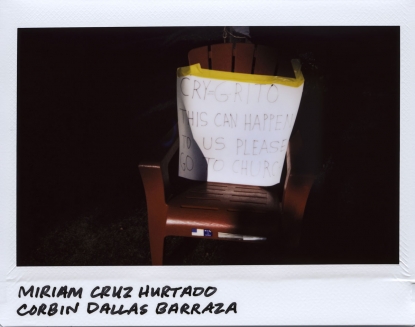

A sign is placed on a chair for the memory of Miriam Cruz Hurtado, 31-years-old, and her son Corbin Dallas Barraza, 4-years-old, in the 1700 block of North Mannheim in Stone Park, Illinois on September 24, 2017.

Hurtado and Barraza were both strangled and stabbed to death at their home on September 21, 2017. Daniel Barraza, 32-year-old, has been charged with two counts of first-degree murder. (AFP / Jim Young)

A sign is placed on a chair for the memory of Miriam Cruz Hurtado, 31-years-old, and her son Corbin Dallas Barraza, 4-years-old, in the 1700 block of North Mannheim in Stone Park, Illinois on September 24, 2017.

Hurtado and Barraza were both strangled and stabbed to death at their home on September 21, 2017. Daniel Barraza, 32-year-old, has been charged with two counts of first-degree murder. (AFP / Jim Young)I began to first think about this project one day when I heard a news story about the 100th homicide in the city this year. And it hit me that in Chicago, a homicide often wasn’t about the person, it was about the number. The 100th person killed. The 200th person killed.

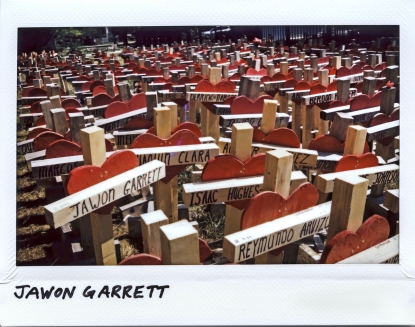

A cross for Jawon Garrett sits among dozens of other crosses at a make-shift memorial for the victims of violence in the 5500 block of South Bishop Street in Chicago, Illinois on September 25, 2017.

Garrett, 40-year-old, died from multiple gunshots to the body in 2300 block of West Madison Street on September 13, 2017. (AFP / Jim Young)

A cross for Jawon Garrett sits among dozens of other crosses at a make-shift memorial for the victims of violence in the 5500 block of South Bishop Street in Chicago, Illinois on September 25, 2017.

Garrett, 40-year-old, died from multiple gunshots to the body in 2300 block of West Madison Street on September 13, 2017. (AFP / Jim Young)So I started visiting the sites where people were killed. I wanted to learn about these people. At first, I wasn’t sure what it was going to turn into. I was going around to the scenes of the murders, but I still hadn’t formed a concrete idea for the project. I didn’t even know if it was going to turn into anything. I was exploring the possibilities.

I started photographing the places visited -- or vigils or funerals if there was nothing to mark the actual place of the killing -- to give a name to the number. I was shooting it all on digital. And then one day I went to the house of a little girl who was reported missing and who was found a few days later underneath the sofa inside the home, dead from asphyxiation.

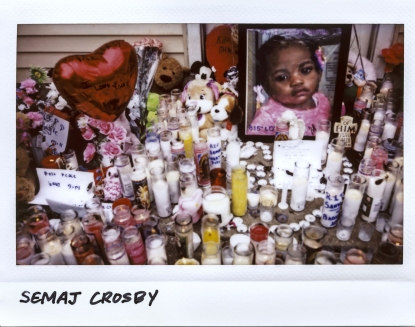

A vigil for Semaj Crosby, 17-month-old, outside her home in the 300 block of Louis Road in Joliet, Illinois on April 28, 2017.

Crosby was reported missing on April 25, but was later found under a couch in her home on April 27. Her death is being ruled as a homicide by asphyxia. No one has been charged in her death. (AFP / Jim Young)

A vigil for Semaj Crosby, 17-month-old, outside her home in the 300 block of Louis Road in Joliet, Illinois on April 28, 2017.

Crosby was reported missing on April 25, but was later found under a couch in her home on April 27. Her death is being ruled as a homicide by asphyxia. No one has been charged in her death. (AFP / Jim Young)Several months later, the police said they were treating the case as a homicide. But when I went there, it wasn’t classified as such yet. I had an instant camera in my backpack, because I had been taking pictures of my daughter with it the day before. So I was shooting the vigil -- people were coming and laying candles -- and I just reached into my bag and took a few with the polaroid. And a person came up to me, curious about the camera and what I was doing. I gave her a picture that I had just taken and she watched it develop.

And as I watched her, something just clicked. A digital picture would end up being stored inside a computer somewhere. A polaroid would be an actual physical memory of the person killed. It was tangible. And then I just knew that this was what I wanted to do. The final touch came when I wrote the victims’ names on the photographs.

That’s when I knew how I wanted to go about the story. Each image represented a person and that person had a name. And the photograph was an actual physical memory of the person.

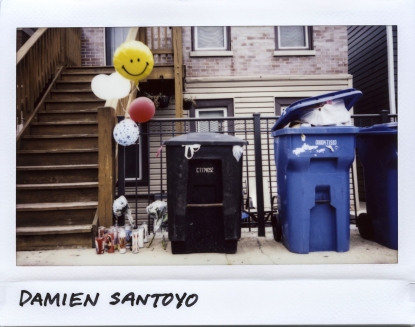

A vigil for Damien Santoyo, 14-year-old, who died on August 6, 2017 on the steps after being shot in the head during a drive-by shooting in the 1700 block of South Newberry Avenue in Chicago, Illinois on August 7, 2017.

(AFP / Jim Young)

A vigil for Damien Santoyo, 14-year-old, who died on August 6, 2017 on the steps after being shot in the head during a drive-by shooting in the 1700 block of South Newberry Avenue in Chicago, Illinois on August 7, 2017.

(AFP / Jim Young)As I went along, I discovered another upside -- the joy that the photos were giving to the victims’ loved ones. I ended up giving out so many pictures during the project. That became a large part of it. The process of watching this tangible memory of the victim appear as a photo was something quite special.

I worked on the project for six months. It involved a constant monitoring of the reports of violence (which in a city as violent as Chicago is a major undertaking in and of itself), researching where the places were, going there, looking for vigils and memorials. I didn’t know when I would stop.

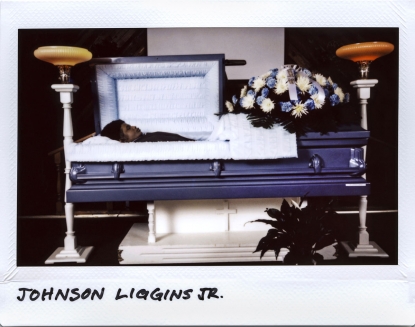

And then one day I shot the wake of Johnson Liggins Jr, a high school senior who was shot to death in the middle of an afternoon in late October as he walked to an after-school job. As I walked to my car afterward, I knew that I was done. Something just clicked again and it became this culmination. I don’t know why. Maybe it’s because it’s the only one where I actually had the victim in the picture. Maybe because by that point I had visited the places of more than 100 homicides.

Johnson John John Liggins Jr.,17-year-old, at the Gatlings Funeral Home in Chicago, Illinois on November 3, 2017.

Higgins died from gunshots to his head and chest in the 8000 block of South Coles Avenue on October 23, 2017. (AFP / Jim Young)

Johnson John John Liggins Jr.,17-year-old, at the Gatlings Funeral Home in Chicago, Illinois on November 3, 2017.

Higgins died from gunshots to his head and chest in the 8000 block of South Coles Avenue on October 23, 2017. (AFP / Jim Young)I’ll of course keep doing projects on violence in Chicago. It’s something that really interests me. I’m originally from Canada, which has less homicides in the entire country in a year than the city of Chicago. I come from a place where if somebody was murdered, it was huge.

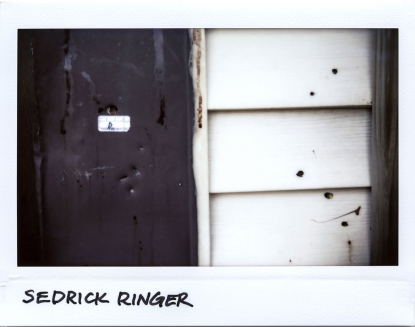

Bullet holes are seen around the front porch where Sedrick Ringer, 50-year-old, was killed in the 5700 block of South Wells Street in Chicago, Illinois on July 3, 2017.

Ringer was shot 9 times and died at the scene June 30, 2017. (AFP / Jim Young)

Bullet holes are seen around the front porch where Sedrick Ringer, 50-year-old, was killed in the 5700 block of South Wells Street in Chicago, Illinois on July 3, 2017.

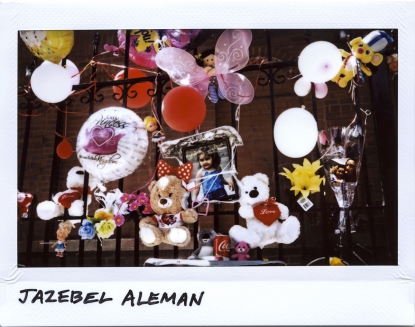

Ringer was shot 9 times and died at the scene June 30, 2017. (AFP / Jim Young)Some of the victims and their stories will stay with me for a long time. Like Jazebel Aleman, a three-year-old girl who was beaten to death with a belt by her father because she wouldn’t eat. Maybe it’s because I have a daughter, but that one just floored me.

Or Cynthia Trevillion, a 64-year-old teacher, who was shot to death in the cross fire of a drive-by shooting while walking to dinner with her husband, about two miles from where I live on the north side. Or Elizabeth Kennedy, a 36-year-old mother stabbed to death in front of her daughter by her ex-boyfriend as she tried to break up an argument between him and another man.

This project is not your classical photo essay. That really came through when I was choosing the photos to include in the final product. Normally in a project like this you choose the best photos. But with these, I didn’t only see the pictures, I saw the stories behind them. Maybe it wasn’t the most interesting picture, but the story behind it affected me in such a way that I couldn’t exclude it. Like little Jazebel beaten to death. I couldn’t have the final product without her.

A memorial for Jazebel Aleman, 3-year-old, near her home in the 2500 block of South Homan Avenue in Chicago, Illinois on June 21, 2017.

Aleman died of multiple injuries resulting from an assault on June 18, 2017. Prosecutors have charged Eduardo Aleman, 26-year-old, with the beating death of his daughter. (AFP / Jim Young)

A memorial for Jazebel Aleman, 3-year-old, near her home in the 2500 block of South Homan Avenue in Chicago, Illinois on June 21, 2017.

Aleman died of multiple injuries resulting from an assault on June 18, 2017. Prosecutors have charged Eduardo Aleman, 26-year-old, with the beating death of his daughter. (AFP / Jim Young)So the project works only if you have both the photos and the words, the story of the person who was killed. But the message, I hope, is still the same. I wanted to take a photograph in a compassionate way that would become a tangible memory from such tragic stories, connecting the victims as a person and not as a statistic.

The bicycles of 5-year-old twins Addison and Makayla Henning are seen on their front lawn in the 400 block of North Reed Street in suburban Joliet, Illinois on August 31, 2017.

The girls died from multiple gun shots to the head and their mother Celisa Henning, 41-year-old, died from a single gunshot on August 28, 2017 in what police are investigating as a murder-suicide. (AFP / Jim Young)

The bicycles of 5-year-old twins Addison and Makayla Henning are seen on their front lawn in the 400 block of North Reed Street in suburban Joliet, Illinois on August 31, 2017.

The girls died from multiple gun shots to the head and their mother Celisa Henning, 41-year-old, died from a single gunshot on August 28, 2017 in what police are investigating as a murder-suicide. (AFP / Jim Young)These are some of the victims of violence. Each photograph represents their murder in Chicagoland. A life lost. Though most of these vigils are gone, their photographs will remain.

This blog was written with Yana Dlugy in Paris.

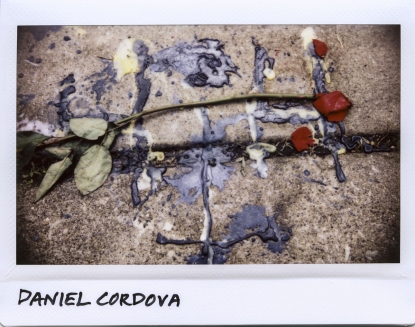

A rose and melted wax from candles used at a vigil for Daniel Cordova, 26-year-old, in the 2500 block of West 46th Place in Chicago, Ilinois on May 8, 2017.

Cordova, was found dead at the scene on May 7, 2017, and died of multiple gunshot wounds. (AFP / Jim Young)

A rose and melted wax from candles used at a vigil for Daniel Cordova, 26-year-old, in the 2500 block of West 46th Place in Chicago, Ilinois on May 8, 2017.

Cordova, was found dead at the scene on May 7, 2017, and died of multiple gunshot wounds. (AFP / Jim Young)