Catalonia passions

Barcelona, Spain -- Catalonia... A difficult crisis to cover. Totally unpredictable, at times hair-tearingly infuriating and so full of passion it's alarming.

When I was sent to Barcelona a week before an independence referendum on October 1, I thought there may be a few days of tumult after the banned vote -- if it actually took place -- but nothing too major.

I even told my dad to come visit me in Madrid on October 5th. He ended up spending much of his holiday in Barcelona.

The story didn't die down for another six weeks, dominating world headlines... and it's still far from over.

(AFP / Javier Soriano)

(AFP / Javier Soriano) (AFP / Pierre-philippe Marcou)

(AFP / Pierre-philippe Marcou)

Never would I have predicted police would try to stop people from voting in the referendum in such a brutal way, even if it had been ruled illegal by the Constitutional Court.

Spanish Guardia Civil guards drag a man outside a polling station in Sant Julia de Ramis, where Catalan president was supposed to vote, on October 1, 2017, on the day of a referendum on independence for Catalonia banned by Madrid.

(AFP / Raymond Roig)

Spanish Guardia Civil guards drag a man outside a polling station in Sant Julia de Ramis, where Catalan president was supposed to vote, on October 1, 2017, on the day of a referendum on independence for Catalonia banned by Madrid.

(AFP / Raymond Roig)I did not expect society would become so polarised, that once-shunned Spanish flags would come back in fashion, that my Madrid friends would get so upset, that anti-independence Catalans would fear speaking out.

Covering this story has been a roller-coaster, an exercise in juggling truths and untruths, with many "I'm sorry, what?" moments thrown in for good measure.

Like that student protest in Barcelona pre-referendum, where between 16,000 and 80,000 people took part according to the police and organisers respectively, in the jovial, peaceful manner that marks all independence rallies.

After it ended, I spoke to a student who was eating her packed lunch with friends.

Why had she protested, I asked. Madrid was repressing them, she responded -- a common allegation as judicial authorities implemented measure after measure to try and stop the upcoming referendum from taking place.

How, I asked? Among the reasons she cited was that central authorities didn't let them protest. Hang on a minute, what have you just done? Oh she was referring to another time.

Three girls walk as they sport Esteladas (Pro-independence Catalan flags) during a pro-referendum demonstration on September 28, 2017 in Barcelona.

(AFP / Pau Barrena)

Three girls walk as they sport Esteladas (Pro-independence Catalan flags) during a pro-referendum demonstration on September 28, 2017 in Barcelona.

(AFP / Pau Barrena) Young girls wrapped in Spanish flags gather during a demonstration against independence of Catalonia called by DENAES foundation for the Spanish Nation Defence at Colon square in Madrid on October 07, 2017.

(AFP / Javier Soriano)

Young girls wrapped in Spanish flags gather during a demonstration against independence of Catalonia called by DENAES foundation for the Spanish Nation Defence at Colon square in Madrid on October 07, 2017.

(AFP / Javier Soriano)

Many Catalans who support independence genuinely feel they have been repressed, especially now that Madrid has imposed direct rule on the once semi-autonomous region to try and stem secessionism, at least until elections next month.

But it's difficult to grasp when you see hundreds of thousands protesting in the streets, or Catalans going about their daily lives just like before.

That may be because I worked in authoritarian China.

When I freely spoke to protesters in the countless rallies I attended in Barcelona, I remembered the "protest park" set up in 2008 in Beijing pre-Olympics to try and allay criticism over China's rights record.

No one ever protested there, save one man whom I interviewed and who was hounded by police afterwards.

Or travelling to Tibetan regions, watching over my back when I spoke to someone to make sure I was not being watched, knowing that person could be detained just for speaking to a reporter.

I guess my experience of repression is pretty severe.

People take part in a demonstration in Barcelona on November 11, 2017 calling for the release of jailed separatist leaders.

(AFP / Josep Lago)

People take part in a demonstration in Barcelona on November 11, 2017 calling for the release of jailed separatist leaders.

(AFP / Josep Lago)The only thing I feel came close to repression was police brutality during the referendum.

I was at a polling station in Barcelona at 5 in the morning, standing in the driving rain along with dozens of others who had showed up to protect the school against a possible police intervention.

After chatting to enthusiastic supporters of independence, I reluctantly left the friendly -- if wet -- atmosphere just before eight and called back to the office.

Shortly after, riot police turned up and brutally dislodged everyone.

I thought of that couple who had turned up to keep an eye on their teenage son. Or the elderly lady waiting patiently under a ledge on a fold-out chair, reading her book. I wonder what happened to them.

People wait under the rain outside the Concepcio School in Barcelona on October 1, 2017 to vote in a referendum on independence for Catalonia banned by Madrid. (AFP / Pau Barrena)

People wait under the rain outside the Concepcio School in Barcelona on October 1, 2017 to vote in a referendum on independence for Catalonia banned by Madrid. (AFP / Pau Barrena)Dozens were injured in police charges in Catalonia, and one man at another polling station lost the sight in his eye when they fired rubber bullets.

After that emotionally-charged day, the crisis escalated, never predictable, and sometimes plain incomprehensible as both Madrid and the separatists played for time.

Take Catalan leader Carles Puigdemont's speech on October 10. Everyone was convinced this was it, that he would declare independence.

And... he wasn't clear. He sort of declared it in a roundabout way, then suspended that kind-of declaration. I would come to dread any of his speeches.

Spain's Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy attends a session of the Lower House of Parliament in Madrid on October 25, 2017.

(AFP / Pierre-philippe Marcou)

Spain's Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy attends a session of the Lower House of Parliament in Madrid on October 25, 2017.

(AFP / Pierre-philippe Marcou) Catalan president Carles Puigdemont attends a session of the Catalan parliament in Barcelona on October 27, 2017.

(AFP / Josep Lago)

Catalan president Carles Puigdemont attends a session of the Catalan parliament in Barcelona on October 27, 2017.

(AFP / Josep Lago)

Coverage aside, one aspect of the crisis that has marked me is the polarisation in Spain.

It was perhaps best illustrated when I came back to Madrid after close to two weeks in Barcelona.

The red and yellow Spanish flag, until then largely shunned because it was often associated with the 1939-1975 dictatorship of Francisco Franco, was suddenly hanging from countless balconies in the Spanish capital.

(AFP / Javier Soriano)

(AFP / Javier Soriano)Three of my neighbours have them hanging from their balconies, though one of them keeps removing and hanging it again -- internal dissent perhaps?

Upon my return, my friends from Madrid were saddened and angry. It was really affecting them.

One of my friends travelled to Hong Kong for work, happy to clear her head.

But even there, as she chatted to colleagues in a bar on October 27, a man who heard her Spanish accent came up to her to inform her the Catalan parliament had just declared independence.

He proceeded to ask why Spain was being so repressive against Catalans -- that allegation again.

And even if she has never supported Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy, blaming him for letting the crisis get out of hand, she felt compelled to defend Spain's decentralised system, which gives a lot of power to its regions.

People wave Spanish flags from the Casa Batllo during a pro-unity demonstration in Barcelona on October 29, 2017.

(AFP / Pierre-philippe Marcou)

People wave Spanish flags from the Casa Batllo during a pro-unity demonstration in Barcelona on October 29, 2017.

(AFP / Pierre-philippe Marcou)Catalans felt the polarisation too.

On the streets of Barcelona, those against independence were either cagey or desperate to talk. But at the end, they rarely wanted to give their surname.

One freelance translator told me her work had dried up after the referendum as companies held back due to the uncertainty.

She said the issue had divided a couple she knew, that she had been called a "fascist" for not supporting independence -- she who had always voted to the left...

She felt "furious," "vulnerable."

An avalanche of worries, echoed among others, that appeared not to register among independence supporters and was ignored by separatist leaders.

That fear of openly speaking out in the deeply divided region -- justified or not -- shocked me.

I even had one independence supporter refuse to give me his name, saying he was worried the police would come after him.

I've never before had to write that so-and-so refused to give their surname for fear of repercussion in Spain. I had to do that a lot in China.

People gather outside the Catalan parliament in Barcelona on October 27, 2017, during a plenary session to debate a motion on declaring independence from Spain.

(AFP / Pau Barrena)

People gather outside the Catalan parliament in Barcelona on October 27, 2017, during a plenary session to debate a motion on declaring independence from Spain.

(AFP / Pau Barrena)Hardest of all for me, though, has been trying to give a succinct explanation as to why some Catalans want independence -- roughly half of the region, it is estimated.

It's a complex, diverse mix of economic, societal, historical reasons, a social malaise aggravated by Spain's devastating crisis.

Essentially though, what I'm starting to realise is that it's pointless trying to find a quick, rational answer to an issue that in many cases comes from the heart.

Like that elderly lady whom I met at a protest. She refused to speak Spanish and would only talk Catalan, the first time that had happened to me.

She described how she had had to pay a coin for every word of Catalan spoken at school under the dictatorship of Franco, who banned official use of the language.

Obviously that is now long gone, but the feeling remains.

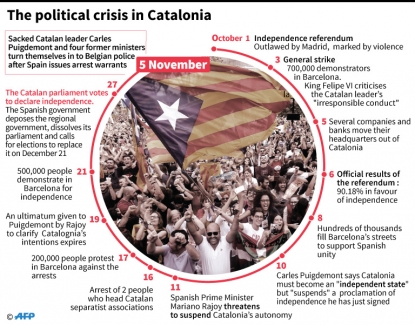

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)

Or the repeated assertions by independence supporters that they feel "humiliated" by the way they have been treated by the central government. One man told me he couldn't sleep for the anger and worry he felt, nor could his father.

They feel Rajoy and his government merely brandished the law -- the referendum was illegal, so were several Catalan laws voted by the majority-separatist parliament -- and made little attempt to win hearts and minds.

Meanwhile, Puigdemont and his ministers have been accused of taking advantage of these feelings to advance their cause, to the expense of other regional issues they should focus on like health, education.

The ruling conservatives have for their part been accused of stoking Spanish nationalism.

Protesters hold Spanish flags during a demonstration called by Societat Civil Catalana (Catalan Civil Society) to support the unity of Spain on October 8, 2017 in Barcelona.

(AFP / Pau Barrena)

Protesters hold Spanish flags during a demonstration called by Societat Civil Catalana (Catalan Civil Society) to support the unity of Spain on October 8, 2017 in Barcelona.

(AFP / Pau Barrena)And as the whole country has its eyes riveted on the crisis, corruption cases involving the PP and Catalan politicians are conveniently forgotten...

Now though, as regional elections approach, independence feels like a far-flung dream.

Puigdemont went to Belgium shortly after the Catalan parliament declared independence along with a couple of former ministers, saying he couldn't get a fair trial here.

A judge jailed other separatist leaders pending a probe into charges of rebellion and sedition -- charges some feel are disproportionate for people who may have broken the law, but were never violent.

But whatever the results of the elections on December 21, I wonder how much the resentment, passions -- and at times plain hysteria -- generated by the crisis has harmed Catalonia, and whether they are here to stay…

A child runs by a Catalonia's independence flag made of 82000 candles in Llivia, in the Spanish Pyrenees near the French and Andorran borders on September 23, 2017. (AFP / Raymond Roig)

A child runs by a Catalonia's independence flag made of 82000 candles in Llivia, in the Spanish Pyrenees near the French and Andorran borders on September 23, 2017. (AFP / Raymond Roig)