The promised land, at last

Jerusalem -- I had waited 25 years to get to Jerusalem. My grandfather used to go there every Friday. He would pray and then go visit friends and family in towns and cities in Israel and the West Bank. But that was in another time, in another world. Before the first intifada.

I am a Palestinian who lives in Gaza, which means that to go to Israel and the West Bank, I need permission from the Israeli authorities, a permit that’s called “tasreeh.” A “tasreeh” is hard to come by. It’s not something that’s given out just like that. You have to have a good reason for wanting to visit. You have to apply. You have to wait. You can’t just say “because I’d like to pray in Jerusalem on Friday like my grandfather used to.” After years of violence and conflict, Israel is very selective about whom it lets in, especially from Gaza.

My first coveted “tasreeh” came in December 2015, after 18 years of waiting and years of applying in vain. Working for AFP had helped. The agency had organized a hostile environment training course in the West Bank and Israel allowed me to attend. To get the permit, I was interviewed at the Erez border crossing for two hours and got the papers three months later. On the day I left, I was detained at the crossing for five hours before finally being allowed to cross. There are no VIPs at Erez -- everyone is questioned and searched the same way.

A Palestinian priest from the Gaza Strip walks through the Erez crossing towards Israel, December 22, 2011. (AFP / Mahmud Hams)

A Palestinian priest from the Gaza Strip walks through the Erez crossing towards Israel, December 22, 2011. (AFP / Mahmud Hams)In the end, the training course was called off at the last minute, so I ended up having a free week. I visited Ramallah, Nablus, Tulkarem and Bethlehem. It was Christmas time, so I ended up having nice pictures from there.

The following year, AFP asked for another pass for me, so that I could participate in a training course in Paris, but I wasn’t allowed to go.

Finally this year I got permission to visit Jerusalem for a week for another training course. I had a few free days afterward, so I wandered around a bit.

I was very excited -- it would be the first time that I would visit Jerusalem in 25 years. The last time I was there was as a 13-year-old boy.

You have to understand, Jerusalem is a mystical place for Muslims. I remember during my visit to the West Bank a few years ago, I could glimpse the dome of Al-Aqsa mosque from the hills of Bethlehem. I really wanted to go there, since I couldn’t remember much from when I was a kid. So when I went now, I made sure to take my camera so that I could take pictures and have a tangible souvenir of the journey. Both to remind myself and to show my family. I was able to pray there and even went for dawn prayers.

Women pray in the shrine under the Dome of the Rock at the Al-Aqsa compound in Jerusalem's Old City, April, 2017.

(AFP / Mahmud Hams)

Women pray in the shrine under the Dome of the Rock at the Al-Aqsa compound in Jerusalem's Old City, April, 2017.

(AFP / Mahmud Hams)The old city was much as I remembered it -- the stalls selling everything from carpets to spices, the constant flow of people through the narrow streets. Al-Aqsa was much as I remembered as well. I made sure to take my camera, as I didn’t know when I'd be able to visit next.

The one thing that was different from 25 years ago was the security. There seemed to be soldiers everywhere, stopping people and checking ID cards. I was stopped five times at the Damascus Gate entrance to the Old City, and was patted down once.

Living in Gaza is a bit like living in a prison, so of course I snatched the opportunity to be able to leave for a bit. But I so wish that my family had been able to join me -- my wife Shaymaa, and my boys -- Ibrahim, 11, Youssef, 9, Mohammad, 7 and Ali, 3. That’s the reason why I took so many pictures -- so they would be able to enjoy the trip virtually. It’s not as good as being there, but it’s better than nothing.

The bustling market streets of Jerusalem's Old City, April, 2017. (AFP / Mahmud Hams)

The bustling market streets of Jerusalem's Old City, April, 2017. (AFP / Mahmud Hams)During my stay I spoke to Israelis in English -- I don’t speak Hebrew and they don’t speak much Arabic. I didn’t advertise the fact that I came from Gaza because I wanted to be treated with respect and wanted to avoid any issues and detentions.

I avoided getting into political conversations as they would probably lead to a dead end.

I did speak to the AFP bureau driver, Mano, who regularly drives to the West Bank and visits with my Palestinian colleagues and has deep roots in the Holy Land -- his family lived for eight generations in Jerusalem’s Old City before 1948.

The Damascus gate leading into the Muslim quarter of Jerusalem's Old City, April, 2017.

(AFP / Mahmud Hams)

The Damascus gate leading into the Muslim quarter of Jerusalem's Old City, April, 2017.

(AFP / Mahmud Hams)We talked about what any two working men and fathers around the world would talk about -- the cost of living and bringing up a family, the price of food, housing, the cost of gas, the size of our homes and what we pay for water and electricity. Every-day normal stuff.

He was surprised at how little electricity we get in Gaza, which has been plagued by supply problems for years. At the moment, Gaza gets two and half hours of electricity per day and each neighborhood gets its turn on a rota. We use car batteries to run a lightbulb at night. Mano was very surprised and asked how we managed. I said we made do.

A Palestinian woman helps her son study by candlelight because of electricity shortages at their makeshift home in the Khan Yunis refugee camp in the southern Gaza Strip, April, 2017.

(AFP / Mahmud Hams)

A Palestinian woman helps her son study by candlelight because of electricity shortages at their makeshift home in the Khan Yunis refugee camp in the southern Gaza Strip, April, 2017.

(AFP / Mahmud Hams)I saw Jerusalem’s light rail line with its sleek trams gliding past and thought how nice it would be to have something similar in Gaza. There used to be a rail line stretching from Jaffa to Cairo. It passed by my ancestral village of Yibna, which my family left along with the rest of the residents during the Arab-Israeli war in 1948, when my father was 11. They eventually settled in a refugee camp in Gaza that was called Yibna because of all the families from the village who settled there.

I remember going to this place with my father and grandfather when I was little, when we could still freely travel through Israel. I remember lots of fields and small houses and gardens, lots of gardens. My grandfather once showed me where our home used to be -- all that was left was a garden wall and part of a room.

The older generation in Gaza remembers that old rail line well. It’s a shame that there are no longer remains of the old stations in cities in Gaza. Imagine that, being able to get on a train and get off in Cairo? No checkpoints, no permits. That would be nice.

The alleys of Jerusalem's Old City, April, 2017.

(AFP / Mahmud Hams)

The alleys of Jerusalem's Old City, April, 2017.

(AFP / Mahmud Hams)Overall, I was more happy than sad on this trip. I hope there is a solution to this never-ending conflict. Gaza has suffered so many wars, so many times, enough is enough. There has to be a solution, why shouldn’t there be? Why can’t people of all religions be able to pray in Jerusalem in their mosque, church and synagogue? It’s their right. Religion should not have anything to do with politics, it should not be mixed into it like it is now.

I hope the next time that I leave Gaza I'll be able to travel with my wife and children, so that I can show them all the lovely places there are to see -- Acre, Jerusalem, Tel Aviv. I hope my children will be able to study in the West Bank, or elsewhere in the world, or Israel, if there is a final peace solution.

This blog was written with Janine Haidar and Yana Dlugy in Paris.

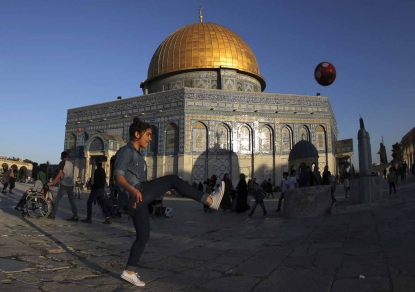

Playing football at the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound, April, 2017.

(AFP / Mahmud Hams)

Playing football at the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound, April, 2017.

(AFP / Mahmud Hams) Playing football at the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound, with the Dome of the Rock in the background, April, 2017.

(AFP / Mahmud Hams)

Playing football at the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound, with the Dome of the Rock in the background, April, 2017.

(AFP / Mahmud Hams)