Pot luck in Uruguay

MONTEVIDEO - As a journalist you have to get out and experience the news on the ground, so it was purely for professional reasons that I went to my local post office in Montevideo to sign up to buy cannabis.

The woman working at the counter was in a flap. The electronic fingerprinting gizmo had scanned my thumb and index finger, but stopped working at my middle finger. As she fiddled with it, I stared at the poster behind her.

It listed the things you're not allowed to send by post. There was a picture of a marijuana leaf. In Uruguay, like most countries, you're not allowed to traffick in marijuana. But unlike most countries, you will soon be able to buy in at the chemist here.

(AFP / Pablo Porciuncula)

(AFP / Pablo Porciuncula)I was one of the first people in the world to become a buyer of legal state-vetted pot, by signing up to the national cannabis register.

Completing the paperwork to get permanent residency in Uruguay -- a necessary step to become a pot buyer -- can take years. But signing onto the cannabis register took minutes. It was easy as buying a stamp.

A woman registers as a marijuana buyer at a state post office in Montevideo on May 2, 2017.

(AFP / Miguel Rojo)

A woman registers as a marijuana buyer at a state post office in Montevideo on May 2, 2017.

(AFP / Miguel Rojo)The register was launched on May 2 -- the last phase of implementation of the most liberal drugs law in the world, in a country of 3.4 million people nestled deep in South America.

From July cannabis, grown in secret state-regulated plantations, is scheduled to go on sale in pharmacies. Buyers will identify themselves by their fingerprints and be allowed to buy 10 grams a week at $1.30 a gram.

The cannabis law made headlines worldwide when it was launched in 2013 by Uruguay's then president, Jose Mujica. A leftist former guerrilla, now 81, he became a liberal idol worldwide for his plain lifestyle and progressive reforms authorizing abortion, gay marriage and cannabis use.

Cannabis for personal use has been tolerated in Uruguay since 1970. Now step by step the new law has given Uruguayans the legal right to grow it in their homes and to form smokers' clubs.

"Grow shops" have sprouted all over the capital Montevideo. But talking the chemists into stocking it took longer.

Many have refused. If they don't sell tobacco or alcohol, they argue, why would they stock weed? So far, only 16 across the country have agreed to sell it, though officials hope that by the end of July the number will have gone up to 30.

A sign indicates that marijuana is not for sale at a shop on the main avenue in Montevideo, May, 2017.

(AFP / Pablo Porciuncula)

A sign indicates that marijuana is not for sale at a shop on the main avenue in Montevideo, May, 2017.

(AFP / Pablo Porciuncula)A poll at the time the law was passed indicated that two thirds of Uruguayans were opposed to the reform.

But this laid-back country, with its hundreds of miles of beaches, seemed open to it when I arrived in July 2014.

One of the first things I noticed in the street was that herby smell in the air.

Markets sell cannabis-scented soap. And makers of the other national herb, mate -- a leaf-based infusion -- have announced plans to release a version containing cannabis.

One of the two brands, Abuelita, has a smiling grandmother on the label. "Stop thinking about life," reads the slogan, "and start living."

Montevideo's first shop dedicated to cannabis, April, 2014.

(AFP / Miguel Rojo)

Montevideo's first shop dedicated to cannabis, April, 2014.

(AFP / Miguel Rojo)Once my fingerprinting was completed, the sales assistant gave me a receipt on post office letterhead, confirming that I was now on the cannabis register. I photographed it and shared it with friends on Facebook. There were two types of reactions. Some assumed I already had the gear on me. Others called into question my professional motives.

To them it was extraordinary. What they didn't grasp, at a distance, was how ordinary cannabis has become here.

Invited to a Uruguayan friend's birthday party, along with teenagers, parents and grandparents, I found, next to the stock of beer, a box of marijuana for guests to share.

All the generations were smoking it.

(AFP / Pablo Porciuncula)

(AFP / Pablo Porciuncula)At another party I was offered marijuana "to take away" like a doggie bag. I'm only an occasional, social, evening smoker. I took it home, found a little box, and like a guilty teenager hid the drug -- from my own kids.

A few weeks later, my daughter lost a baby tooth. Once the tooth fairy had retrieved it at night, I searched for something to keep it in. I thought I had found the perfect little box. But once I'd opened it, the reek told me it was wrong to store a child's tooth in there. It was full of weed.

I was one of 568 people who signed up on the first day, according to the Cannabis Control and Regulation Institute. By June 4, there were 3, 853 of us. That is on top of the 6,811 already registered as home-growers, and the 59 official smokers' clubs.

In downtown Montevideo, my colleague Mauricio Rabuffetti, AFP's local Uruguay beat reporter, interviewed some of the first Uruguayans to sign up to the buyers' register.

"It's better, more efficient and safer," said shop worker Yamila, 26, who has been buying it on the black market until now. That "is very expensive and you don't know what you're taking."

Smoking away during a pro-marijuana rally in Montevideo, May, 2014.

(AFP / Miguel Rojo)

Smoking away during a pro-marijuana rally in Montevideo, May, 2014.

(AFP / Miguel Rojo)Another, 63-year-old retiree Beatriz, said she was first offered marijuana by her son 20 years ago. "Do you want to kill me?" she said at the time. She eventually tried it four years ago. Now she smokes it with her grandchildren. "It's good for the asthma," she says.

Aiming to undermine the illegal drugs trade, Uruguay is the first country to legalize consumption of the drug all the way from production to sale. But it is wary of becoming a destination for drug tourists.

The "grow shops" have signs in their windows explaining that only Uruguayans or permanent residents are allowed to take advantage of the cannabis law.

Luckily, after two years of waiting, I got my residency papers a few months ago. So now I will be able to experience this story, and bring it to my readers, first-hand. The sacrifices one makes for one’s profession….

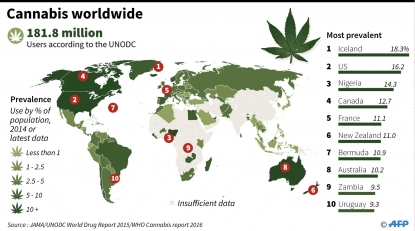

(AFP / Graphics)

(AFP / Graphics)