Namaste Nepal

KATHMANDU -- I didn't expect to cover so much tragedy when I began my posting in Nepal.

My three-year tenure was punctuated by natural disasters, deadly protests and a months-long blockade along the Nepal-India border that choked off essential supplies to a country already reeling from its worst earthquake in 80 years.

Along the way, I travelled to some of the world's most inaccessible and stunning spots -- often on foot -- and met some extraordinary people.

Initially, I could scarcely believe that I was being paid to spend my days walking in the Himalayas, where gods dwell and men die. A world more magical and moving than any place I had ever known.

(AFP / Roberto Schmidt)

(AFP / Roberto Schmidt)It felt like the best job in the world.

And then an earthquake hit Nepal.

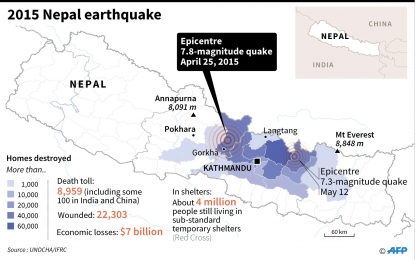

((AFP Graphics))

((AFP Graphics))Avalanches tore down mountain slopes, centuries-old temples collapsed, more than half a million people were left homeless and nearly 9,000 died as a result of the earthquake and its aftershocks.

Clearing rubble at Kathmandu's Narayan temple, May 2015.

(AFP / Nicolas Asfouri)

Clearing rubble at Kathmandu's Narayan temple, May 2015.

(AFP / Nicolas Asfouri)I was on assignment at Everest base camp with AFP's South Asia photo chief, Roberto Schmidt, when the quake struck, triggering an avalanche that buried us alive.

An avalanche rushes towards Everest base camp, April 25, 2015. (AFP / Roberto Schmidt)

An avalanche rushes towards Everest base camp, April 25, 2015. (AFP / Roberto Schmidt)Our Nepali trekking guide, Pasang Sherpa, dug us out of the snow. He saved our lives.

Over the next several months, I travelled to many of the worst-affected areas to report on the aftermath of the disaster.

A village in the Dhading district, some 60 kilometres northwest of Kathmandu, May, 2015.

(AFP / Prakash Mathema)

A village in the Dhading district, some 60 kilometres northwest of Kathmandu, May, 2015.

(AFP / Prakash Mathema)And about a year later, Pasang, AFP photographer, Prakash Mathema, and I trekked to Langtang -- a village that was obliterated by a monster avalanche triggered by the earthquake.

Few tourists have returned to Nepal since the quake and the hike to Langtang was unusually quiet except for the sight of villagers working to repair parts of the trail.

Nepali workers restore a trail in Langtang valley, April, 2016.

(AFP / Prakash Mathema)

Nepali workers restore a trail in Langtang valley, April, 2016.

(AFP / Prakash Mathema)The village itself looked like a lunar landscape.

The avalanche, travelling at high speed, blasted across the Langtang valley floor with a force equivalent to more than half the strength of the nuclear bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

It stripped the bark from trees and flung them across the valley, plastering the surrounding hills with flattened trunks.

No one there stood a chance -- more than 300 locals and tourists died and only a handful of villagers, trapped under the rubble, survived the catastrophe.

Nepalese porters carry rebuilding supplies to the village of Langtang, April, 2016.

(AFP / Prakash Mathema)

Nepalese porters carry rebuilding supplies to the village of Langtang, April, 2016.

(AFP / Prakash Mathema)A year on, the place felt heavy with grief.

And yet, each morning, I awoke to the sounds of villagers working hard to rebuild homes in the shadow of the mountain that wrecked their lives.

We stayed in the village's only guesthouse -- its tin and plywood walls were put up weeks before our arrival.

Like thousands of quake victims across the country, people in Langtang have received little help from the government, apart from an initial payout of around $150.

It's the same story in other disaster-hit areas. Nepal has seen three prime ministers in three years but politicians appear to do little beyond mouthing platitudes about the “resilience” of Nepalis who are expected to recover from tragedies just like that.

They are expected to be brave enough to fight wars for foreign governments, as Gurkha soldiers have done for the British and Indian armies, or climb the world's highest mountains again and again, or work on construction sites abroad until they drop dead from exhaustion.

It's a grim picture and it's given me plenty to write about -- journalism is rarely about success stories and happy endings.

A man stands amid the rubble of his house, two days after it was destroyed in an earthquake, 13, 2015.

(AFP / Roberto Schmidt)

A man stands amid the rubble of his house, two days after it was destroyed in an earthquake, 13, 2015.

(AFP / Roberto Schmidt)At its best, the business of reporting bad news can shine a light on injustice and spark change.

At its worst, it can feel exploitative and self-serving, as it did occasionally in the months following the earthquake.

Each time I would head out to interview an earthquake victim, I would brace myself as I prepared to ask people barely hanging on to life about the loved ones they had lost, the dreams they had relinquished, their fears for the future.

Clearing rubble at the Narayan temple in Kathmandu, May, 2015.

(AFP / Menahem Kahana)

Clearing rubble at the Narayan temple in Kathmandu, May, 2015.

(AFP / Menahem Kahana)Each time I would walk away, I would tell myself that the stories would remind readers overseas to donate to aid efforts in Nepal. Sometimes they did.

An earthquake survivor in a village in the Gorkha district, May, 2015.

(AFP / Philippe Lopez)

An earthquake survivor in a village in the Gorkha district, May, 2015.

(AFP / Philippe Lopez)But back in Kathmandu, it often seemed as though every bleak headline only helped to bolster the cynics so they could shrug their shoulders and intone: "nothing will ever change in Nepal".

Faith and fatalism come up a lot during conversations in Nepal -- a buffer against nature's cruelty and human indifference.

I have struggled to understand it -- this acceptance of the unacceptable, exemplified by the popular Nepali phrase, "ke garne" or "what can one do?"

As I prepare to say goodbye to Nepal, it's hard not to be dismayed at the slow pace of recovery.

It's difficult not to feel overwhelmed by the scale of the task that lies ahead for the millions still living in shelters or in damaged, unsafe homes.

And yet, I cannot be cynical about a place and people who have come to mean so much to me.

The fact is, however much Nepalis may like to say "ke garne" to every calamity that strikes them, they are doing plenty to improve their lives and the lives of others.

Author (right) with Pasang Sherpa on their arrival to Kathmandu from Everest Base Camp on April 29, 2015.

(AFP / Prakash Singh)

Author (right) with Pasang Sherpa on their arrival to Kathmandu from Everest Base Camp on April 29, 2015.

(AFP / Prakash Singh)I have met a homeless quake survivor working as a porter to deliver aid, a nurse who swapped her comfortable digs in Kathmandu to travel to far-flung villages, a surgeon who has devoted his life to helping disabled children walk again.

And I have met a trekking guide whose humour, courage and generosity will always remind me that there is a brighter world inside us than we realise. It may not always be reflected in the world outside, but it's there.

It's why I remain hopeful about Nepal's prospects -- not because its people are resilient, but because so many of them are as exceptional, as inspiring as the mountains surrounding them.

(AFP / Roberto Schmidt)

(AFP / Roberto Schmidt)