The slippery slope to a banana republic

BRASILIA -- There was a moment at the height of Brazil’s titanic impeachment crisis when the whole thing boiled down to one tiny detail -- what to do with those portraits?

The little-loved elected leftist president Dilma Rousseff had left her presidential palace to start a six-month suspension. Her little-loved, conservative vice-president, political nemesis and replacement was about to move in.

One of the portraits. (AFP / Presidencia / Roberto Stuckert Filho)

One of the portraits. (AFP / Presidencia / Roberto Stuckert Filho)But there was the issue of all those Rousseff portraits dotting the palace.

Suddenly Brazil’s new leadership, which had so ruthlessly and efficiently pushed Rousseff from office halfway through her second term -- sparking accusations of a coup d’etat -- looked hesitant and confused.

And no wonder. The problem was that officially, Rousseff was only temporarily suspended. Until a Senate trial definitively removed her from office, Temer was only an acting president.

So what to do: celebrate victory by ditching her smiling pictures or leave them up in case, however unlikely it seems, she ended up returning?

At first, the portraits did start coming down. In one of those made-for-the-movies regime change moments, a handyman was seen struggling to remove a particularly big version of the picture, featuring Rousseff in her presidential sash.

But then Temer himself intervened, ordering the pictures to be left up.

To me the controversy summed up nicely the surreal nature of Brazil's slide from global economic and political star just a few years ago toward a banana republic-style slapstick comedy.

A market in Manaus, Brazil. November, 2013.

(AFP / Yasuyoshi Chiba)

A market in Manaus, Brazil. November, 2013.

(AFP / Yasuyoshi Chiba)And althouth the portraits may have been a detail, there's nothing tiny about the power struggle in the country.

At stake is leadership of Latin America’s biggest nation, one of the world’s biggest economies, home to the world’s biggest rainforest and a lot of the world’s raw materials, oh, and host of the Rio Olympics in less than three months. Some would go further and say that Latin American democracy itself – a shaky issue over the years – is in play.

To find out just exactly what was going on with the portraits, I headed to the press office on the first floor of the presidential palace, a magnificent building of sharp angles, sexy curves, glass and marble from Oscar Niemeyer's breathtaking 1950s design.

But up there, I got the run-around from a charming and smooth-spoken media relations expert -- what you might call a flack -- who claimed erroneously that there'd never been any plot against the portraits.

So I made my way down to the bowels of the administration building, where civil servants work in warrens of tiny offices. Here the atmosphere was decidedly less-polished and very nervous: the country they served hung at the edge of the unknown, just like those pictures.

Dilma Rousseff supporters in Sao Paulo follow Congressional debate on impeachment on April 17.

(AFP / Miguel Schincariol)

Dilma Rousseff supporters in Sao Paulo follow Congressional debate on impeachment on April 17.

(AFP / Miguel Schincariol)"What we've heard is that someone could come to collect them, but that they'll be put in a safe place until it's known if she's coming back," one functionary told me, speaking in a hushed voice about how she agreed with Rousseff’s claim to be the victim of a coup.

"For me the portrait should stay there -- right until 2018 when she finishes her mandate," another office worker said, referring to Rousseff’s second term.

“Don’t put our names,” she joked. “They’ll send us to the guillotine.”

I've seen plenty of banana republic tragi-comedy during the years that I spent covering the ex-Soviet Union.

There were those magically predictable elections of Nursultan Nazarbayev in Kazakhstan, where the father of the nation’s vote tally has risen steadily over the decades to the high 90 percentile. No wonder he can get away with building a tower in his own honour with a golden imprint of his right hand at the top.

Then there was Ukraine, where despite the extraordinary courage of pro-democracy protesters, the country remains riddled with government corruption, incompetence and thieving oligarchs. Indeed, the Kremlin’s English-language mouthpiece Russia Todaypithily summed up Ukraine on its website as “a Banana Republic, without bananas.”

But of course, Russian state media should know: Vladimir Putin has used his seemingly endless rule to perfect the cocktail of faked elections, crony capitalism, police brutality and cult of personality that goes a long way toward the definition of banana republics.

Brazil, though, was a more hopeful country -- or so I'd thought.

Guards at the presidential palace in Brasilia.

(AFP / Vanderlei Almeida)

Guards at the presidential palace in Brasilia.

(AFP / Vanderlei Almeida)But now I found myself observing an all-night Senate session in the capital Brasilia, which was about to throw Brazil into circus-like turmoil.

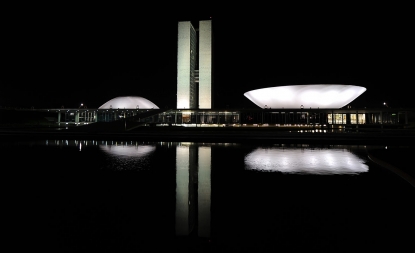

It must be said that the capital is already a very odd place. Built from scratch in a barren region at the end of the 1950s, this was meant to be Brazil's city of the future.

The Cathedral in Brasilia, June, 2014. (AFP / Odd Andersen)

The Cathedral in Brasilia, June, 2014. (AFP / Odd Andersen)Remarkably, the Niemeyer buildings -- for example, a museum and cathedral resembling spaceships -- still look futuristic. Sadly, the rest of the center -- a depressing, scraggly and characterless place bereft of shops, cafes, restaurants or other signs of life -- failed tomatch those ambitions.

The result is a city that looks not so much like the future as a shiny but mysterious and now useless object from the past.

Consisting of two skinny towers and two bowls (one turned upside down and one the right way up), the Congress building is one of the more arresting sights.

(AFP / Vanderlei Almeida)

(AFP / Vanderlei Almeida)What happens inside is crazier still.

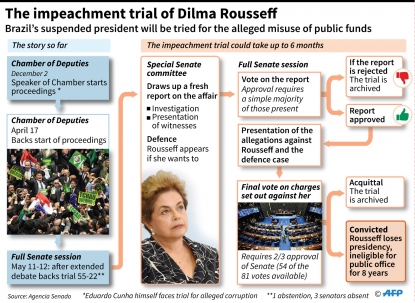

That night, I watched senators bulldoze their way toward a vote suspending Rousseff to face trial on charges that she took unauthorized loans to patch holes in the state budget. She doesn't deny this but says it was an accounting sleight of hand that has always been common practice and doesn’t amount to an impeachable crime.

Outwardly, the scene in the Senate chamber was much as I'd expected from the country's senior legislative body.

The Senate during the impeachment debate. May 11, 2016. (AFP / Evaristo Sa)

The Senate during the impeachment debate. May 11, 2016. (AFP / Evaristo Sa)Decorum was observed. The halls were lined with stirring references to Brazil’s history and the national flag and its rather awkward motto of “Order and Progress” hung in places of honor. Journalists and other visitors had to wear a jacket and tie just to enter. My usual Rio de Janeiro flipflops had no place.

For sure this wasn't Congress's lower house. There, a few weeks earlier, deputies had punched each other, sung, waved flags, jeered and grinned for selfies with their wives while making histrionic speeches condemning Rousseff.

(AFP / Evaristo Sa)

(AFP / Evaristo Sa)The Senate was better behaved.

But under the polished surface was another extraordinary scandal: as many as 60 percent of those well-dressed, carefully coiffed senators had current or past brushes with the law, in some cases serious cases involving massive bribe taking and embezzlement. And they had their share of weird moments.

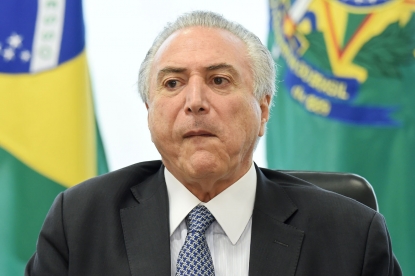

Temer, the president in waiting, fell asleep before the vote, according to local media, only to be woken by the sound of firecrackers ignited by celebrating anti-Rousseff activists, people who are always in carnival mode however serious the moment.

Michel Temer (AFP / Evaristo Sa)

Michel Temer (AFP / Evaristo Sa)Then there was Senate President Renan Calheiros, a genial looking man but a big name on that list of corruption suspects.

He was giving a television interview during the all-night marathon when something quite large and white flew from his mouth. He kept talking as if nothing had happened.

Chewing gum? A tooth? The video went viral but the truth remained unknown.

The truth about Rousseff’s impeachment was not much clearer.

Even if the budget manipulations were illegal, it’s not sure that’s really why she faces being ejected from office.

(AFP / Vanderlei Almeida)

(AFP / Vanderlei Almeida)Many Brazilians see Rousseff being removed for purely political, not legal reasons. They see her being removed because she was incompetent, because she presided over economic decline and didn’t know how to negotiate with Congress. And for a majority of Brazilians that’s enough.

But in a serious democracy can you impeach a president basically because you don't like her?

'Bye darling,' reads the sign. (AFP / Tasso Marcelo)

'Bye darling,' reads the sign. (AFP / Tasso Marcelo)After the Senate vote finally came through at 6:34 am, overwhelmingly in favor of Rousseff's impeachment, I went into the government square to get reactions from ordinary people. However, the square, flanked by the legislative, executive and Supreme Court buildings, had been blocked off by police and was eerily deserted, as if life had been sucked out of Brazilian politics itself.

Soon the inhospitable Brasilia sun was so hot that the tarmac started to shimmer, accentuating the emptiness of the place. I went to sit in a bus stop not because there were any buses -- there were no vehicles at all -- but because there was shade.

Here, I ran into a group of policemen. They were arguing. I eavesdropped.

"Tell me one thing she's done, tell me that," an officer said.

"She did the accounting tricks," a comrade replied.

"But what were they -- can you even explain?" the first one shot back.

I was strangely comforted to realize I wasn't the only one bewildered.

((AFP Graphics))

((AFP Graphics))That morning, Rousseff walked out of her presidential palace, officially to start her suspension, but in reality quite possibly never to return again.

And just as Temer would have his headache over the portraits a short while later, she had her own symbolism dilemma: which door to use?

The back door promised minimal drama but looked sneaky. A central exit which opens onto a long ramp would maximize the theater, but might seem too final. So a regular front door was chosen – she would walk out as if going for a stroll.

Staff and supporters cried as the country’s first female president took that long, slow walk to her waiting motorcade.

Rousseff, who was tortured by Brazil’s military leaders in the 1970s, kept her eyes dry. But she looked reluctant to get into the black car.

Just before she did, she turned around and blew a kiss to the crowd, her final act.

Dilma Rousseff leaves the presidential palace. (AFP / Andressa Anholete)

Dilma Rousseff leaves the presidential palace. (AFP / Andressa Anholete)Now it is was Temer’s time.

(AFP / Brazilian Vice Presidency / Marcos Correa)

(AFP / Brazilian Vice Presidency / Marcos Correa)And after a sleepless, foodless night it was time for this reporter to make a dash to the presidential palace cafeteria. Serving a square meal at heavily subsidized prices, the cafeteria was a rare oasis from the culinary wastelands of the capital’s center. Besides, the joke was already going around that Temer, a markets-orientated centrist, would soon ditch such an unprofitable relic of Rousseff’s leftist rule.

As for Brazilians, they’d already got what they wanted that night. They’d pushed their unpopular president aside.

The bizarre thing, though, was that now they were waking up to life under a man they hated just as much. Polls show that two percent would vote for Temer, who had only been vice president because his center-right party and Rousseff's Workers' Party were in a coalition.

Here he was, though, striding into the presidential palace, a 75-year-old backroom dealer at the pinnacle of power without a single ballot being cast.

(AFP / Andressa Anholete)

(AFP / Andressa Anholete)Temer's opening act was to announce radical alterations to the leftist policies which got Rousseff elected in 2014 with 54 million votes. To prove his point, he immediately picked a cabinet of exclusively white men.

This throwback to the mid-20th century was shocking in a country which had just had a woman president and where more than half the population is non-white. His reaction to the uproar, promising to enrol “members of the feminine world,” only made things worse.

Covering Temer and his lookalike elderly, rich, white male colleagues in those initial hours made me suspect I'd been transported into some alternate reality. And there was something niggling me about Temer, with his high forehead, his hollow cheeks and thin smile.

Whom did he look like?

(AFP / Evaristo Sa)

(AFP / Evaristo Sa)An opponent once likened Temer to a "butler in a horror movie." But there was another cinema reference making the rounds of Brazilian social media which made even better sense: Count Dracula -- specifically the version played by Bela Lugosi in 1931. Brazil's acting president is a dead ringer.

Anyone who knows this amazing country and its humorous, warm people will hope the impeachment story doesn't end up as a horror film.

It's possible that Temer might turn out to be the architect of "national salvation" that he promises to be. It's possible that Rousseff will survive her Senate trial and come back to power. Brazil might get a happy ending.

But from what I saw in Brasilia, not too many Brazilians would dare predict the future. There's nothing more slippery than the path to becoming a banana republic.

The presidential palace at night. (AFP / Vanderlei Almeida)

The presidential palace at night. (AFP / Vanderlei Almeida)