The mosquito from hell

Salvador de Bahia, Brazil, February 5, 2016 -- Infernal heat fills the waiting room of the pediatric neurology department, a heat against which the few fans buzzing away on the wall seem powerless. Seated on the chairs are mothers and couples. The babies that they cradle with such love will probably not be able to speak, or walk, or develop normal intellectual abilities.

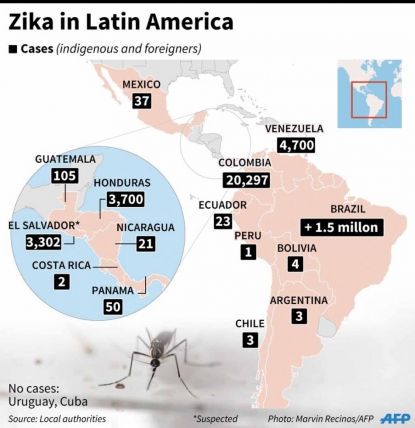

I and the rest of the AFP team are in Salvador de Bahia, in Brazil’s northeast. It’s one of the Latin American regions most affected by the Zika virus, which is spread by mosquitoes and when caught by a pregnant woman is suspected of causing microcephaly, a congenital condition where the head is smaller than normal and the brain under-developed.

The virus has so far spread to 26 countries in South and Central America and the Caribbean and health authorities have warned it could affect up to four million people on the continent and spread worldwide, with first cases already reported in Europe.

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)It breaks my heart to see these children and their parents at the Sister Dulce, a Catholic hospital in Salvador, where a non-governmental organization provides care for the poor. Each case of microcephaly is unique and the degree of the damage depends on the zone of the brain that is affected. But it’s not an exaggeration to say that each of these babies will become a handicapped child and then adult, in families that have very few resources to take care of them.

A couple agrees to talk to us. “When he was born, it dropped on us like a bomb,” says Mateus, the father. “I had so many dreams for him. I wanted him to do sports, to play, to be healthy and strong…” In his arms is little Pietro, their first child.

“I caught Zika in my fifth month of pregnancy,” says Kleisse, the mother. The symptoms seemed benign -- fever, headache, pain in the joints. “I went to the doctor and was told that there was no risk, neither for the baby or me. But when he was born on November 22, we were told he has microcephaly and we understood that he would never be normal.”

As they speak to us, the two parents tenderly caress their little boy.

Matheus and Kleisse with Pietro. January, 2016. (AFP / Christophe Simon)

Matheus and Kleisse with Pietro. January, 2016. (AFP / Christophe Simon)The next day, we go to their house. They live in a favela, one of Brazil’s myriad of poor neighborhoods. Although theirs has electricity and basic public services, it’s still a favela, with houses piled up on top of each other, dogs in the street, small bars and shops. There are no parks, no libraries, no public transport. And no medical facilities.

'Democratic' virus?

Their house is narrow and warm, devoid of any decorations except for a few family photos. In the main room there is a television and a fan. Kleisse explains to me that running water is often cut here, so people stock up. In such a tropical climate, stagnant water is a favorite habitat for the mosquitoes that carry Zika.

That’s one of the cruelties of this virus -- the speed with which it has spread in Brazil is partly due to the lack of basic public services and the high number of people living in poverty. Later, an official with the Bahia health authorities would tell us that it’s a “democratic” virus that can afflict anyone, no matter their social class. But even he will admit that there are more chances of contracting it by people who live in non air-conditioned houses, in winding streets infested by mosquitoes, where water is stocked up because of incessant cuts.

A graveyard is fumigated in Peru in an effort to prevent the spread of the Zika virus. January, 2016. (AFP / Ernesto Benavides)

A graveyard is fumigated in Peru in an effort to prevent the spread of the Zika virus. January, 2016. (AFP / Ernesto Benavides)“If I had known, I would have paid more attention, I would have protected myself with anti-mosquito spray,” says Kleisse. “Mosquitoes have always been a problem here, and now this.”

“They are mosquitoes from hell,” cries out her husband.

Aedes Aegypti mosquitoes in a lab in San Salvador. February, 2016. (AFP / Marvin Recinos)

Aedes Aegypti mosquitoes in a lab in San Salvador. February, 2016. (AFP / Marvin Recinos)Kleisse, Mateus and their baby live in Mateus’s mother’s house. She has been unemployed for quite some time and Kleisse is on maternity leave from her job as a sales clerk. She thought she would return to work after having the baby. But the more likely scenario now is that she will have to take care of her handicapped child full-time. She is not sure she will qualify to receive welfare benefits. According to information that she has been able to gather so far, that type of government aid is reserved for families that are even poorer than hers.

Another couple that we met lives three hours away from the hospital. Who will pay for their trips? For the moment, they can carry their baby in their arms. But what will they do when he becomes bigger? They are a young couple of modest means. They couldn’t talk to me for too long because they had to catch the next bus to return home.

A physical therapist with a microcephalia-afflicted infant in Salvador, Brazil. January, 2016. (AFP / Christophe Simon)

A physical therapist with a microcephalia-afflicted infant in Salvador, Brazil. January, 2016. (AFP / Christophe Simon)When you’re covering a story like this, the most difficult thing is to make people talk. I am never at ease heaping questions of victims of any type of tragedy. Each question seems invasive to me. One of families that I approach refuses to have their photo taken or to answer any questions. They tell me bitterly that because of us, they’re going to have to wait longer to see the doctor, as we spent time interviewing him. I don’t know what to reply.

Click here to view on a mobile device

One of the delicate issues raised by this virus is the question of abortion. In Brazil, abortion is only allowed in extreme cases -- if the mother’s life is in danger, if the pregnancy is a result of rape, or if the fetus is afflicted with anencephaly. Microcephaly is not on the list of accepted conditions. Women afflicted with Zika cannot, for the moment, decide for themselves whether they’ll continue the pregnancy or not. At least in theory.

Because, as for a lot of things, it all depends on your social class. “Abortion is already free in Brazil,” a celebrated doctor said recently. “It’s just a matter of money to have it performed in reasonable conditions. The rest are lies and hypocrisy.”

Countries advise to put off pregnancies

Brazil is a country with a huge Catholic population and its conservative parliament is looking to tighten the already strict anti-abortion legislation. Those attempts sparked massive demonstrations by women last year. But to be honest, many Brazilian women would not choose to abort even if they knew that their baby will be born handicapped. Some at the Salvador hospital told me so themselves.

The virus -- which at the moment has no treatment -- has sparked a lot of panic in Brazil and neighboring countries, as it has spread with alarming speed. Some Latin American countries are advising couples to avoid getting pregnant altogether for the moment.

A classroom is fumigated against mosquitoes in Honduras. February, 2016. (AFP / Orlando Sierra)

A classroom is fumigated against mosquitoes in Honduras. February, 2016. (AFP / Orlando Sierra)I will remember the microcephalic children that I saw for a long time. During my reporting trip to Bahia, I received numerous messages from my friends. Like me, they don’t plan to have kids until they have established a career and they are worried by what they are reading in my stories.

“Am I never going to be able to become a mother?” asked one.

Natalia Ramos is an AFP journalist based in Sao Paulo. This blog was translated by Roland de Courson into French and by Yana Dlugy into English.

Kleisse with Pietro at home. January, 2016. (AFP / Christophe Simon)

Kleisse with Pietro at home. January, 2016. (AFP / Christophe Simon)