'Leave them the hell alone'

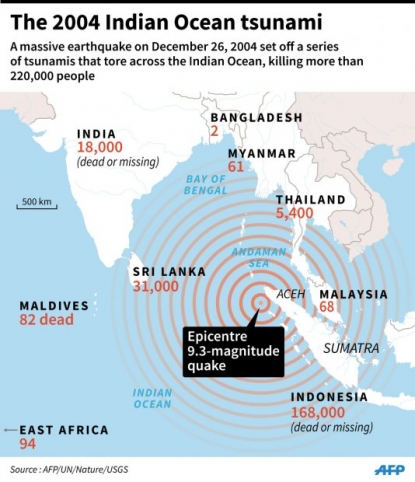

PARIS, December 23, 2014 – It all begins with a glance at the AFP wire, over breakfast, on a cool morning in Hanoi. A tsunami has struck in the Indian Ocean. Indonesia, Thailand and Sri Lanka have all been hit. More than 100,000 people are dead or missing, and the toll is surging by the hour.

It is the day after Christmas, everyone is on leave and this is what we – in our clinical jargon – call a top world story. In other words, there’s a fair chance Hong Kong, our Asia headquarters, will call to ask me for help. Do I want to go? Travel to the heart of a terrible story, and fight to get the news out to the world?

No, I don’t. I know the enduring myth of the hero-journalist. But the truth is we don’t necessarily, at all times, under all circumstances, feel up to it. Right now I am tired, and could do with a break.

A tsunami wave comes crashing ashore on December 26, 2004 at Koh Raya in the Andaman islands, 23 kilometres from Phuket (AFP Photo / John Russell)

A tsunami wave comes crashing ashore on December 26, 2004 at Koh Raya in the Andaman islands, 23 kilometres from Phuket (AFP Photo / John Russell)My objections don’t stand up for long. “We have no one in the region. Seriously, I need you there,” I am told. So I am off to India. Half an hour later, that changes to Aceh, Indonesia. No, hang on: “Go to Bangkok, we’ll see when you get there. I think you’ll take another flight to Phuket. There are lots of foreign tourists caught up in this.”

I’m now reading the AFP news wire in a whole new way – scanning for hard facts: what is the situation on the ground? What exactly happened in Phuket? What state is the town in? Will planes be able to land? Will there be electricity?

I know a colleague is leaving for Sri Lanka, another for Aceh, that reinforcements are coming to Bangkok, that photographers are coming in from all over. At times like this, AFP’s global machinery sets into motion with an efficiency like no other.

My head is filling with a haze of images, along with a sense of gravity at what awaits me. There will be bodies, suffering, hard times. I may not have anywhere to sleep. I’ll have to find ways to send my stories. Do I want to go, now? The question is irrelevant. I am going.

I can feel the adrenalin rising a little, and the apprehension too. And I have one certainty. A feeling I struggle to explain but have felt before in extreme situations: I am going to see terrible things, but I wouldn’t switch places with anyone, not for the world. My wife understands my decision to go, but I’m not sure what she is thinking. I am already far away, and she can tell I am.

At the airport in Phuket, I wait at the carousel for my suitcase. I shared the flight with NGO workers, cameramen and a few tourists – oblivious to what they are heading into. I call Bangkok where my colleague Philippe Agret, who happened to be holidaying in the Gulf of Thailand, has been called in to oversee the coverage. I am pleased to hear it: we know each other well. We like and respect one another, and that is sure to help.

A street in Phuket a few hours after the tsunami on December 26, 2004 (AFP)

A street in Phuket a few hours after the tsunami on December 26, 2004 (AFP)“I need a good story, well written, a scene piece – can you give me a line?” he asks.

“Sure, but I’m at the airport right now. Not sure what I’m going to find. When do you need to know?”

“Well, ideally now. But just do your best. »

'Washing machine'

Ninety minutes of traffic jam later, I’m trekking around central Phuket looking for a hotel room. Everything is full. The sea is three kilometres away and in the busy afternoon atmosphere it is as if nothing has happened. A hotel landlady ends up offering me a room at her own home.

A few minutes later at reception I run into a young Australian man. Dan has a broken shoulder, several dozen stitches on his face and bruises all over his body. He has been going back and forth between the hotel and the hospital to get his dressings changed.

I base my first story on him. He tells me about the wave, the fear, the water that picked him up and tossed him in all directions. I write about the “washing machine” feeling he describes. I still have no idea. I have seen nothing . Hell is three kilometres away.

Injured tourists wait at Phuket International Hospital on December 26, 2004 (AFP / Saeed Khan)

Injured tourists wait at Phuket International Hospital on December 26, 2004 (AFP / Saeed Khan)Day two. More AFP colleagues have arrived. A Thai reporter is covering the local villages swept away by the wave. An English-speaking writer heads north, to a beach that was completely devastated. Corpses strung up in the trees. I focus on the rescue coordination centre. It is based inside the town hall, a white building set in a huge garden with well-clipped shrubs.

This is where the travel operators, diplomats and foreign rescue organisations are headquartered. And it is where the survivors come searching for help, haggard with shock and grief. One lady is looking for her mother. A couple has lost its children. They squint at the vast billboards where people have pinned photographs, notes, phone numbers, calls for help.

A man is looking for his wife and son, who both carry the same name as mine. I linger over their picture for a little longer...

A Buddhist monk looks at missing person notices at Phuket hospital on January 5, 2005 (AFP Photo / Pornchai Kittiwongsakul)

A Buddhist monk looks at missing person notices at Phuket hospital on January 5, 2005 (AFP Photo / Pornchai Kittiwongsakul)Travel agent employees try to trace their missing customers, do the rounds of the hotels, count bodies from a distance. I go by the hospital, meet the staff there. Inside the eight refrigerators are full. All contain two bodies instead of one. A dozen more bodies lie in the corridor, covered with a simple sheet, at the mercy of the heat and humidity.

Corridor of death

It is starting to get to me. And I have barely seen a single body. Which is odd, for a journalist sent to cover a natural disaster. If I let myself, I could almost feel guilty at the thought my colleagues are out there doing the dirty work. The old journalist-hero myth again…

I leave for Khao Lak, a beach two to three hours’ drive north, home to the French-owned Sofitel Blue Lagoon. A hotel laid out in a U-shape opposite the ocean. At one end is the reception which sounded the alert. Too late. The deadly wave surged in and out of the corridor. Left behind are a few bodies, teddy bears, suitcases, the watermark 2.5-metres high, and an abominable stench.

A woman searches for loved ones at a temple in Takuapa, December 28, 2004 (AFP Photo / Saeed Khan )

A woman searches for loved ones at a temple in Takuapa, December 28, 2004 (AFP Photo / Saeed Khan )The sea is turquoise, birds are singing. Hell made only the briefest of appearances here. I try to talk with the hotel staff, but I can tell many journalists have been here before me. The words aren’t coming out any more.

The right thing?

I file my report with a satellite phone and hitch a ride back to Phuket. I ask to be dropped at the airport. People of all ages are milling around in a daze, beyond exhausted. Young women in tears. Backpackers in flip-flops, staring into the middle distance. Broken, middle-aged men. There will be empty seats on the flight home.

I have to go and talk to them. It’s my job, it’s what I am paid to do. Two cameramen turn up, virtually running to get their soundbites. “How do you feel? Can you tell us?” I am ashamed of them, my belly twists in pain, and I end up leaving without talking to anyone.

Did I do the right thing? Ten years later I know there is no right answer. I did what my gut feeling commanded. Leave them the hell alone –you can see they’re suffering.

A Thai woman cries after identifying her husband's body at Patong morgue on December 27, 2004 (AFP Photo / Saeed Khan)

A Thai woman cries after identifying her husband's body at Patong morgue on December 27, 2004 (AFP Photo / Saeed Khan)Every morning I talk with my friend Philippe, filling in as bureau chief in Bangkok. “Are you OK?” he asks. “Yes, yes, I’m fine.” “You sure?” “Yes.” It’s the truth. But I’m still grateful for the question. I head back to the crisis centre, where it is proving increasingly tricky to sort the dead from the missing, the missing feared dead, the missing probably still alive but not yet located, and the people who have already gone home.

Tug of war over rotting bodies

The authorities have opened a website to post more photos online. But this time the pictures are of dead bodies. It’s the only hope left for the living to find their loved ones. The faces are swollen, often beyond recognition, ready to burst under the effect of the heat. Truth be told, the survivors look pretty awful themselves.

Whatever you do, don’t cry. I try to remember I am not the one in pain here. Listen, watch and work. Each time I sit down at my laptop I am seized by this indescribable feeling: I love this job, even if – because? – it sometimes pushes me beyond my limits.

The unidentified body of a foreigner at Patong morgue on December 29, 2004 (AFP Photo / Romeo Gacad)

The unidentified body of a foreigner at Patong morgue on December 29, 2004 (AFP Photo / Romeo Gacad)The morgues are overflowing and there aren’t the means to keep the bodies cold. The French gendarmes charged with identifying them have arrived, but they don’t have the authorization to start working. For a battle is playing out behind the scenes. Western countries want to keep the bodies intact for as long as possible to have a chance of identifying them using dental records, skeletal analysis, even DNA. But there is a huge risk of contamination in the tropical heat and Thai culture demands that they be incinerated.

It soon turns into a political tug-of-war, with thousands of puffy, rotting corpses the prize. They are all anyone is talking about at this stage– although they are kept hidden from view. I go back to the wall full of pictures of the missing. But I am finding it harder and harder to look at them for any length of time. With every passing day, there is less chance any of them will turn up alive.

Medics carry an unidentified tsunami victim in Thailand's Phang Nga province, January 9, 2005 (AFP Photo / Peter Parks)

Medics carry an unidentified tsunami victim in Thailand's Phang Nga province, January 9, 2005 (AFP Photo / Peter Parks)One photo has the word “Found!” written joyously beside it. At least there is some good news out there. We hear of a boat with its seven-man crew, who were diving in the Andaman Sea and miraculously escaped the carnage. It feels good to share a happy story.

The first wave takes his son, the second his wife

But we soon fall back to reality. To the story of this man, who was holding his wife and son by the hand. The first wave took his child, the second his wife. And he was left there, petrified with impotence and guilt that he couldn’t hold them safe.

And the terrible questions gnawing at everyone. What name, what life, what story lies behind this body? And this one? Where is my wife, my sister, my niece, my father? Where are they rotting away?

“It’s another trauma for the survivors to endure,” a rescue worker tells me. “They have no coffin, no burial, no way of making the death seem real. People are unable to leave. As long as they haven’t seen a body, they can’t accept it.”

A Canadian volunteer helps people searching for missing relatives in Patong on December 28, 2004 (AFP Photo / Romeo Gacad)

A Canadian volunteer helps people searching for missing relatives in Patong on December 28, 2004 (AFP Photo / Romeo Gacad)In the lobby of a five-star hotel, on New Year’s Eve, the pianist tinkles away like any other night. We have come for drink with a colleague from Le Figaro, to try to clear our heads for an hour or two. I spend my days talking about dead bodies, but I am haunted by the living.

On a sofa opposite the entrance, a man has placed a hand on his wife’s shoulder. She looks devastated. He says nothing, he’s said it all already and it wasn’t enough. How many children did they lose? One? Two? I watch them from afar, a knot in my stomach. I keep my distance, almost bothered by their presence. They make my own discomfort seem futile. I down one beer, then a second, and that’s it.

A stench you cannot escape

The gendarmes tell us about their work back in Paris, the forensic investigations, the disaster operations. They have little to do with the suffering of the living. They spend their time opening plastic bags. Pull on the zipper, with scented cotton wool stuffed in your nostrils to keep out the stench of death. Because it is a smell you cannot get rid of. I wish I had known that before going up to Khao Lak.

More than 600 bodies waiting to be identified in a temple in Khao Lak on December 29, 2004 (AFP Photo / Saeed Khan)

More than 600 bodies waiting to be identified in a temple in Khao Lak on December 29, 2004 (AFP Photo / Saeed Khan)The gendarmes are still not allowed to do any work. The political quarrel goes on. So they dabble in gallows humour: “And in the meantime, they’re getting puffier…” Together we cackle at the thought. We all need the distraction of a joke – however tasteless.

Nine days have gone by. Fresh AFP reinforcements have arrived and a colleague is coming to take over from me in the field. I asked for it not to go on much longer. It’s not ideal for the agency. Sending in another reporter costs money. But they understand – and no one complains.

I hear that a photographer colleague in Asia switched off his mobile phone for 48 hours. Really? So others found it hard too, then?

I fly back to Hanoi and go home. My 18-month-old son is waiting for me at the door, and runs to greet me. I take him in my arms, and squeeze him all over telling myself the wave didn’t take him, at least. I cry, for a long time. His mother forbids me from watching television. I mustn’t see any more of these pictures. I mustn’t see any more bodies. It’s time for me to return to the land of the living. My work in the field has eaten away at me. It’s time to claim back my freedom.

Didier Lauras was sent to Thailand to cover the aftermath of the Indian Ocean tsunami on December 26, 2004. He is now AFP chief editor for France.

A ceremony for tsunami victims on board a Thai aircraft-carrier, January 28, 2005 (AFP Photo / Pornchai Kittiwongsakul)

A ceremony for tsunami victims on board a Thai aircraft-carrier, January 28, 2005 (AFP Photo / Pornchai Kittiwongsakul)