India through a lens

NEW DELHI, December 19, 2014 - When the 20-year-old Rajeev Goswami set himself on fire at a student protest in 1990, R. Raveendran captured the desperate act on camera -- a shot that triggered a surging wave of demonstrations, and indirectly brought down the Indian government.

Ravee -- as he is universally known -- has finally hung up his camera after a four-decade career covering a staggering range of subjects, from an outbreak of plague to cricket World Cup triumph.

An institution at AFP's Delhi's office, the veteran photographer looked back on his journey in a chat with his long-time colleague Indranil Mukherjee, reminiscing about some of his biggest scoops and the technological changes he has been witness to.

"I joined the agency in 1973 as one of two teleprinter operators. Apart from us, the only other staff were the bureau chief, the Indian reporter Dilip Ganguly and a librarian," he said.

In those days, Ravee used to cycle every story round to the government-run Overseas Communication Service (OCS). A particularly thankless task during the Indian Emergency from June 1975 to March 1977 when prime minister Indira Gandhi suspended elections, locked up opponents and curtailed basic rights.

Young Indian women show off their palms decorated with a paste known as 'Mehndi' during a contest in New Delhi (AFP Photo / Raveendran)

"Back then, the reporters would type up stories on a typewriter, maybe three or four a day, and I would cycle round to the home affairs ministry where censors would have to give their approval.

"They would read the story, and cross out anything they didn't approve of. Basically, if you wrote about Indira or something that they felt was supportive of the opposition they would reject it.

"Once they were satisfied, they would give it their stamp of approval and then I would go round to the OCS and punch in each story, letter by letter with a code, on a teleprinter.

"It would take about 20 minutes for each story but if the line was bad, you might have to start all over again. You would send to London and then it got sent on to Paris."

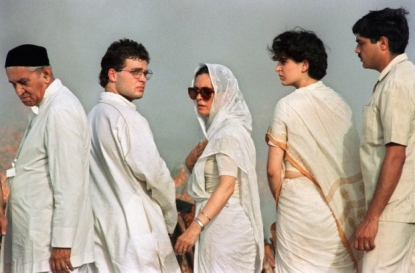

India's Premier Rajiv Gandhi, his wife Sonia and daughter Priyanka at the cremation of Indira Gandhi. (AFP Photo / Gabriel Duval)

India's Premier Rajiv Gandhi, his wife Sonia and daughter Priyanka at the cremation of Indira Gandhi. (AFP Photo / Gabriel Duval)"Back in the 1970s, Delhi only filed text and the first photo production from the bureau only came in October 1984 when Indira Gandhi was assassinated by her Sikh bodyguards. The first pictures were black and white images of the massive crowds lining the streets as her body was taken for cremation. They had to be sent via Tokyo where the photo editor would then decide which ones he wanted in colour.

"It was a fairly mundane morning when the news of the assassination broke and then suddenly I was plunged head first into one of the biggest stories in India's history since independence.

"Not only did I have to type up and transmit the alerts and copy about the assassination but I was also entrusted with the task of picking up photographs from freelancers.

"In a way that one incident changed my life. It was my initiation into the world of photojournalism."

Indian victims of the 1984 Bhopal gas tragedy at a protest in New Delhi on July 25, 2005 (AFP Photo / Raveendran)

Indian victims of the 1984 Bhopal gas tragedy at a protest in New Delhi on July 25, 2005 (AFP Photo / Raveendran)Weeks later, India was again at the centre of world news with the Bhopal gas tragedy, hastening AFP's decision to establish a full-time photo service in Delhi. The first chief photographer was Douglas Curran who took Ravee under his wing and taught him the tricks of the trade.

"In those days we had to send our photos through a high resolution drum scanner to Tokyo. If it was coloured, we had to do three individual transmissions for each image.

"My first color photograph was a demonstration by India's Communist party, which got me my first front cover of Newsweek."

It was the first of many. One week Ravee made the front page of Time and Newsweek and Paris Match all in one go for his coverage of a plague outbreak in the western state of Gujarat in 1994.

Indian women burn rubbish in an area affected by pneumonic plague in Surat,

some 240 miles north of Mumbai on September 26, 1994(AFP Photo / Raveendran)

"The plague down in Surat was probably my biggest major assignment. Back in those days, we hadn't even heard of protective gear and safety suits.

"Not many photographers wanted to go down there for obvious reasons. There were bodies everywhere and the place was teeming with rats."

Proud as he is of the Surat coverage, perhaps his most memorable -- and momentous -- picture came four years earlier when he was covering demonstrations by upper caste students against planned job reservations in the public sector for members of India's lower castes.

A policeman directs traffic during an outbreak of pneumonic plague in the west Indian city of Surat, on September 30, 1994 (AFP Photo / Raveendran)

A policeman directs traffic during an outbreak of pneumonic plague in the west Indian city of Surat, on September 30, 1994 (AFP Photo / Raveendran)"Protests had erupted all over the country and I was covering them on a daily basis. On the morning of September 19, I and a few other photographers got news that some student groups in the Deshbandhu College at Kalkaji (a northern suburb of Delhi) were preparing for some sort of a violent agitation.

"We were waiting outside the main gates when suddenly, a student was in flames right in front of us.

"I jumped over the fence and ran towards the burning Goswami and started taking photos. I knew I had canned it but was a bit anxious until I processed the film. Once Doug saw the negative he gave a wink and raised an invisible toast to me.

"My picture was on the front pages of all the Indian newspapers the next day and seemed to serve as the spark for a whole series of similar protests that engulfed India in the next days and weeks."

Those protests were seen as instrumental in the downfall of prime minister VP Singh's government and Ravee was later summoned to an official commission of inquiry to give his version of events. Goswami survived the incident, but suffered from serious ill health as a result, dying at the age of 33.

A youth removing a campaign poster of assassinated former Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi from his residence n Delhi on May 22, 1991 (AFP Photo / Raveendran)

A youth removing a campaign poster of assassinated former Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi from his residence n Delhi on May 22, 1991 (AFP Photo / Raveendran)

Sonia Gandhi, the widow of late Indian Premier Rajiv Gandhi, her daughter Priyanka (R) and son Rahul (2nd-L), in New Delhi

at the murdered leader's funeral on May 24, 1991 (AFP Photo / Raveendran)

The list of stories he covered reads like a potted history of India in the last 30 years, including the 1991 assassination of Rajiv Gandhi and the 2004 tsunami which left a trail of death and destruction in parts of India and neighbouring Sri Lanka -- one of Ravee's regular assignment destinations.

Sri Lankan girls mourn their parents killed in the Indian Ocean tsunami. December 28, 2004 (AFP Photo / Raveendran)

Sri Lankan girls mourn their parents killed in the Indian Ocean tsunami. December 28, 2004 (AFP Photo / Raveendran)He can well remember the deadly communal violence in Gujarat in 2002 in which more than a thousand people -- mainly Muslims -- died.

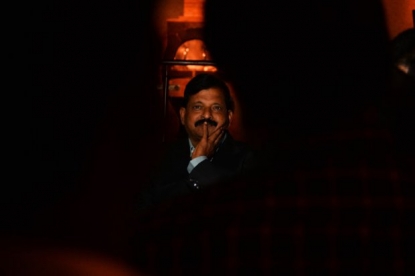

The chief minister at the time was called Narendra Modi, and Ravee was on hand 12 years later when the same man romped to victory in India's general election of May 2014.

Supporters celebrate the election victory of Narendra Modi's Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party on May 16, 2014

(AFP Photo / Raveendran)

Amid the unrest and political upheaval, he was also a witness to some of the most uplifting moments in India's recent history, including the outpouring of joy when it won the cricket World Cup on home soil in 2011.

"It's been a fascinating last four decades," he said. "I wouldn't change it for anything and I wouldn't have wanted it any different."

Raveendran at his AFP farewell party on Oct 31, 2014 (AFP Photo / Chandan Khanna)

Raveendran at his AFP farewell party on Oct 31, 2014 (AFP Photo / Chandan Khanna)