Watching a world come tumbling down

(AFP Photo / Patrick Hertzog)

BERLIN, Nov. 7, 2014 - If you climb onto a chair and twist over a bit, you can almost see, from the window of AFP's Germany office, the place where it stood -- in between two futuristic buildings that have since shot up on Berlin's Potsdamer Platz.

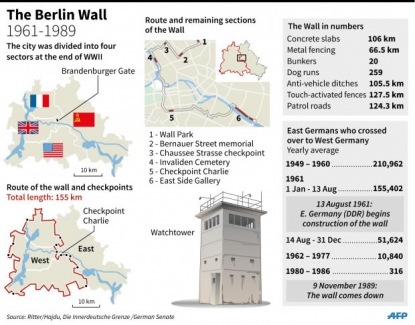

Every day on the way to work we cycle, walk or drive across the phantom line, etched out by two rows of paving stones and the words "Berliner Mauer, 1961-1989."

Twenty five years ago, on November 9, 1989, the Berlin Wall came crumbling down in a rush of euphoria. Torn down in the space of a few hours by tens of thousands of Berliners come to claim back the freedom stolen from them 28 years earlier, on the night of August 13, 1961, when the Wall of Shame went up.

That night an ecstatic crowd chanted "Open the door!" (Tor Auf! Tor Auf!) before the amazed eyes of AFP reporters who knew they were witnessing history in the making.

"It's the only time in my life I cried while covering a story. It was so powerful I can still remember it exactly," said Luc de Barochez, head of AFP's Bonn bureau at the time, sent to report from East Berlin.

East German border guards demolish a section of the Berlin Wall early November 11, 1989 (AFP Photo / Gerard Malie)

East German border guards demolish a section of the Berlin Wall early November 11, 1989 (AFP Photo / Gerard Malie)"Sometimes, if I'm feeling down -- which I rarely do -- I think back to that day. It's like a yardstick for beautiful things," recalls Richard Ingham, who watched the wall come down from both sides.

"I felt that I was on a story that was going to change the world, and it was a privilege."

"We saw a world come tumbling down before our eyes, it was mind-blowing," said Yacine Le Forestier, who covered the story as a young reporter in the West German capital.

But he also remembers the "stress and the sweaty palms on both sides as people struggled to understand what was gong on. Everyone was just stunned."

For before the first pickaxes sunk into the concrete, sending sparkling wine corks flying into the icy night, reporters covering the momentous event were carried away on a rollercoaster sparked by two words: "Sofort, unverzueglich". "With immediate effect."

The words were those of Guenter Schabowski, spokesman for the Communist East German government, addressing the world's media at a press conference in East Berlin earlier that evening. They were to change the course of the 20th century.

'With immediate effect'

The East German protest movement had been snowballing for weeks, clamouring under the windows of a Stalinist regime that was clinging on even as the wind of perestroika blew threw the Soviet Union.

Tens of thousands of East Germans had already fled to the West via Hungary or Czechoslovakia.

It was 6:53 pm on Thursday, November 9. At a press briefing on the communist party's latest decisions, Schabowski pulled a piece of paper from his pocket.

Click here to watch this video from a mobile device.

Before a room packed with international media, he announced that East Germany's leaders had decided to grant its citizens full rights to travel abroad.

"When will that come into force?" asked a journalist. Schabowski did not have a ready-made answer -- his bosses had not given him the details.

So he improvised: "As far as I know, with immediate effect."

If East Germans were now free to come and go, the Berlin Wall had lost its raison d'etre. But none of the journalists present could contemplate such an earthquake. No one took the full measure of what the grey-suited official had just said -- barring the correspondent for Italian agency ANSA, who rushed out of the room and telegraphed his editor in Rome. "The wall has fallen", he wrote (it took some time for the editor to believe him and file the story).

Checkpoint Charlie, in 1968 (AFP Photo)

Checkpoint Charlie, in 1968 (AFP Photo)"We didn't hit the button right away," said Le Forestier who was following the press conference on television from Bonn.

"He didn't say they were opening up the Wall. The announcement was something far more administrative. We all understood it would come into force quickly -- but not that very night!" de Barochez, who was at the news conference.

At 7:04 pm, the official East German news agency ADN published its account of "Schabo's" announcement, along with "pages and pages filled with the bureaucratic details of the new measures relaxing travel rules," said Le Forestier.

A few minutes later, AFP sent its first news alert.

"There was a moment of silence in the newsroom, where we all just looked at each other," said Le Forestier.

This was AFP's first story:

Berliners demolish a section of the wall in order to open a new crossing point on 11 November 1989

(AFP Photo / Gerard Malie)

"East Germany decided on Thursday to fully open its borders with immediate effect to those of its citizens who wish to permanently emigrate, Guenter Schabowski of the SED communist party politburo announced in East Berlin."

It was followed by another urgent announcing that the decision also applied to those who wanted to travel to West Germany.

Then came a torrent of news stories, "all evening and all through the night," said Le Forestier.

'Madness! Delirium!'

By that point West German media had latched on to what was happening. The main evening news on ARD public television opened with the headline: "The GDR is opening up its borders". The newsreader added: "Superlatives should always be handled with care... But tonight we can risk saying that November 9 is a historic day."

At 8:22 pm in Bonn, West German lawmakers adjourned their session of parliament, rose to their feet and began singing the national anthem.

Berliners party in front of the Wall at the Brandenburg Gate on November 15, 1989 (AFP Photo / Gerard Malie)

Berliners party in front of the Wall at the Brandenburg Gate on November 15, 1989 (AFP Photo / Gerard Malie)The former chancellor Willy Brandt, who had engineered a rapprochement with the Communist bloc in the 1970s, was in tears.

"News of the GDR's decision to open the inter-German border was greeted with a thunder of applause in the Bundestag," reported Frederic Bichon, AFP's Bonn correspondent who left the next day for East Berlin.

By then de Barochez had made it back from the press conference to AFP's tiny East Berlin office where the team was bursting with excitement.

They had seen nothing yet.

"We heard there was something going on by the Wall, so we headed to Checkpoint Charlie, the only place where foreigners could cross between East and West Berlin," said de Barochez.

Berliners crowd atop the Berlin Wall near the Brandenburg Gate on 11 November 1989 (AFP Photo / Gerard Malie)

Berliners crowd atop the Berlin Wall near the Brandenburg Gate on 11 November 1989 (AFP Photo / Gerard Malie)On the other side, Richard Ingham was there, notebook in hand.

"It was bitterly cold, and I was pretty much the only person standing there," said Ingham, who had sent out his urgent series in English from the East Berlin office before heading over to the West side.

But as evening drew on, and word of mouth spread, huge crowds headed spontaneously to the Wall, plastered with graffiti on the West side, spotless on the East.

On the West, "they started chanting, 'We want to drink a coffee on the Alex'," short for Alexanderplatz, the main square in East Berlin, recalled Ingham.

"From the other side you could hear the East Berliners whistling and shouting," he said. "A shiver ran through the crowd" -- aware amid the excitement that things could easily take a sinister turn.

"It was barely five months since the Tiananmen Square massacre," Ingham said.

And then suddenly, at 11:30 pm, the border guards who no longer knew how to contain the crowd -- acting without orders from above -- opened up a crossing point. Then another one.

Young West Berliners, perched on top of the Berlin Wall, remove a piece of it, on November 16, 1989

(AFP Photo / Patrick Hertzog)

"And then it was just madness! Madness! Delirium!" said Ingham. "We grabbed bottles of bubbly and showered it over cars -- it was just the most utter joy."

De Barochez recalls the same ecstatic scenes.

"It was like pulling the plug on an overflowing sink. People were jumping onto the Wall, gripping on, climbing over. The border guards were there but they weren't moving."

'One letter at a time'

Back then, of course, there was no Internet, no real-time transmission. Reporting on such a historic event was pretty much mission impossible.

Mobile phones? "They were the size of a suitcase. You've got to imagine these things that weighed a ton, that you had to lug around," said de Barochez. "Fixed line networks were very weak -- all it took was three people phoning at the same time for it all to stop working."

East German Trabants flow towards West Berlin on November 21, 1989 (AFP Photo / Gerard Malie)

East German Trabants flow towards West Berlin on November 21, 1989 (AFP Photo / Gerard Malie)On the western side, the nearest phone booth was several hundred metres from the Wall. "It was exhausting -- we spent our time running back and forth," said Bichon.

As for written transmission, it was all by telex.

"You hit the keys and that punched holes into the paper tape -- which you fed into a machine and it came out the other end in Paris," explains a reporter.

When you were out in the field, remembered Le Forestier, "you had to find a hotel, you would unscrew part of the phone and hook up the machine."

"Transmitting could take forever -- it was virtually one letter at a time, and sometimes it would fail and you'd have to start all over again."

"We produced nothing like as much coverage as we do these days, because technically it was so difficult," said Bichon.

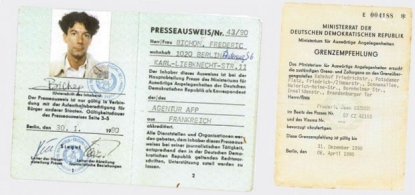

AFP East-Berlin correspondent Frédéric Bichon's GDR press card (left) and his special permit for using border crossings other than Checkpoint Charlie, normally the only one open to foreigners in Berlin. The permit would have expired three months after the German Democratic Republic ceased to exist (courtesy Frédéric Bichon)

"If you managed to write a story and send it on the same day, it was like travelling to the end of the world and back," said Bichon, who would criss-cross East Germany's rocky roads on countless reporting assignments in the months that followed.

AFP immediately sent in reinforcements, from Bonn and Paris.

Jean-Louis de la Vaissiere was with the first East Germans to discover the capitalist West during the weekend of euphoria that followed.

"The underground train was so packed that it couldn't pull out of the station."

On the Ku'damm -- West Berlin's answer to the Champs Elysees -- he described East Berliners pushing up in awe against the windows of luxury stores.

De la Vaissiere wrote back then of "monster queues 250 to 300 metres long stretching outside banks", which were offering a bonus to new customers from the East.

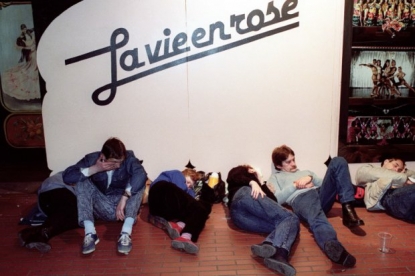

AFP covered all aspects of the peaceful revolution, including the discovery of the West German sex trade.

Tired East Germans rest in front of the cabaret 'La vie en rose' on Kurfurstendamm, on November 12, 1989

(AFP Photo / Gilles Leimdorfer)

In one piece, de la Vaissiere wrote of "a note in the window of the Sexyland peep-show, warning that 'Today we'll open at 2 pm instead of 10 am. The show's stars -- Nora and Charly -- are resting after a tough Sunday."

The memory of those tumultuous weeks stayed keenly alive with the reporters lucky enough to witness them.

"When the Wall was breached for the first time at the Brandenburg Gate, I was watching from an observation platform with an American colleague," said Bichon, the current head of AFP's Berlin bureau.

"This was a guy who had been through it all as a war reporter. But he started crying his eyes out."

These days when the AFP team head to grab a sandwich on the Potsdamer Platz, they'll often slow to ponder how -- 25 years ago -- two thick concrete walls, a tangle of barbed wire, watchtowers and a No Man's Land would have stood in their path.

Yannick Pasquet is an AFP reporter based in Berlin.

A stamp to cross the Wall eastwards, a stamp to cross west: passport pages were quick to fill up for a foreign correspondent reporting from Berlin in 1989 ! (courtesy Frédéric Bichon)