From AFP Beirut to First Lady of Afghanistan

KABUL, November 7, 2014 - She is one of the key personalities of the new Afghanistan. First lady since September, the former journalist of Lebanese Christian heritage has already broken some taboos.

After several weeks of talks with her office, we are able to arrange a meeting. Mrs Ghani would like to speak of her exposure to French culture – from her homeland, to time as a student in Paris in the late 1960s…and to AFP, where she briefly worked during her youth.

Rula Ghani is the wife of new Afghan President Ashraf Ghani. He has bestowed upon her the name “Bibi Gul” to signify his respect toward her. ‘Bibi’ is a respectful term for an older woman, and a name given to pious and pure women. ‘Gul’, which means flower, is a suffix added on to many names in Afghanistan.

During the election campaign, she appeared alongside her husband and made at least one public speech. The president for his part thanked her in his inauguration address – a significant event in Afghanistan that had conservatives gritting their teeth.

Afghan then president-elect Ashraf Ghani and his wife at their residence in Kabul on April 14, 2014 (AFP Photo / Wakil Kohsar)

Afghan then president-elect Ashraf Ghani and his wife at their residence in Kabul on April 14, 2014 (AFP Photo / Wakil Kohsar)According to the local press, it is the first time the spouse of an Afghan leader has been so visibile since Queen Soraya, wife of King Amanullah in the 1920s.

Before our visit, “Bibi Gul” had already received some media, but the interview with us is different in one way: it was the first she would give in French, in a country where along with the local languages Pashto and Dari, English reigns supreme.

The departure of Hamid Karzai, who had been president since fall of the Taliban in 2001, had begun a new chapter in Afghan history. Rula Ghani wanted to make use of the opportunity. Not only by appearing in public, but by participating in the debate on women’s rights in Afghanistan.

Supporters of Afghan presidential candidate Ashraf Ghani gather in Kunduz on March 19, 2014 (AFP Photo / Shah Marai)

Supporters of Afghan presidential candidate Ashraf Ghani gather in Kunduz on March 19, 2014 (AFP Photo / Shah Marai)It is no easy task in this conservative Muslim country where her Christian heritage is often highlighted, especially by critics of her husband. She is careful to state therefore that she won’t involve herself directly in politics and that Afghan women themselves are already leading the charge for rights.

Banned pens in the presidential palace

We were invited to the presidential palace on October 30, as a team of four: video reporter Clotilde Gourlet, English speaking journalist Issam Ahmed, photographer Shah Marai and myself.

The huge fortress with ultra-high security and tall castellated walls opens its doors to us after three consecutive security checks and a few thorough body searches. The guards takes our mobile phones and has a dog sniffs our cameras.

I did not take a pen with me. They are systematically seized, for fear that they could contain some dangerous or explosive product, and the presidency provides its own pencils to visiting journalists.

AFP reporters Clotilde Gourlet, Issam Ahmed and Emmanuel Parisse interview Mrs Ghani on October 30, 2014

(AFP Photo / Shah Marai)

Our recording devices have to be switched on in the presence of the security officers to show them that they really work and that no explosives are hidden in them. Finally, we are taken in a car to the office of Mrs Ghani: a separate building within the premises of the palace, surrounded by a pretty rose garden.

As we enter her office huge body guards closely follow us. The first lady is sitting, and gets up to greet us in flawless French. The interview will last half an hour, much more time than she had initially agreed to give us.

“ Bibi Gul “ is an intellectual. She does not want to repeat what she has already discussed with our English speaking colleagues. She wants first of all to talk in French about the years she spent studying in Paris, of May 1968 protests in France, and of her experience in the city’s intellectual circles, of her stint at AFP in Beirut in the beginning of the 70s.

Sitting on a large armchair, close to an Afghan flag, this 66 year old lady with a friendly smile welcomes us her head covered with the Hermes scarf that she was using at the end of the 60s in Paris. She found it in one of her drawers and makes a point to wear it today.

Students and riot police clash in Paris on May 6, 1968 (AFP Photo)

Students and riot police clash in Paris on May 6, 1968 (AFP Photo)“ I remember very clearly that all the girls who were studying at Science Po were carrying a little Hermès scarf and would cover their heads with it when they would come out of school. All of us had our own way to hang it to our bag, “ she says with a touch of nostalgia in her voice.

She also recalls the three years spent around ‘Boulevard Saint-Germain’, a hub of intellectual activity. “These were very important formative years, these were years when you read a lot, when you read all kinds of books, novels, philosophical essays. I acquired this as part of my education in French. And when I went back to Lebanon and joined the American University I had trouble speaking English “

Politics and empty bottles

In one anecdote, she tells us about her attachment to the French world view which she held on to. “I often went to dinners in the United States where I said things that were very French in their outlook.

“I thought back to one of my professors at Sciences Po, Pierre Georges who taught on political parties. He used to say ‘Political parties in the US are a bit like two empty bottles with different labels.’ And I said this once at a dinner in the United States and of course the Americans weren’t happy. I said it once and I did not repeat it. But it’s just to illustrate how I had taken on board the French way of thinking.”

She observed with great interest the student uprisings of May 1968, which Sciences Po played a major role in, though admitted “I wasn’t politically mature at the time.”

In the summer of 1969 she graduate from Sciences Po and joined the AFP bureau in Beirut, where her family lived.

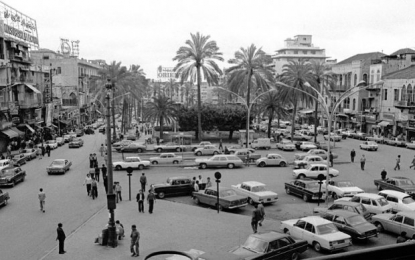

Downtown Beirut in the early 1970s (AFP Photo)

Downtown Beirut in the early 1970s (AFP Photo)“ I was given the task at first to do the press review. Which meant I was in the early shift – which started at 6 o'clock in the morning and finished at 1 o'clock, early afternoon.”

She said her time at the agency taught her the values of speed and accuracy. Between 6am and 8am, she had to read newspapers from Lebanon, Syria, Egypt and Iraq. There was no time to waste – it was up to her to catch any news that her organization had missed.

“At the same time I was part of the team that was doing the listening of radios,” she said, recalling with amusement the giant tape recorders used in that era. The journalists had to juggle between different stations and not miss a thing. – “And that was very important at the time because there were a lot of coups d'etats happening,” she said.

“It was a wire service so it was a great training for a journalist because it taught you to be quick but at the same time you had to be accurate,” she added. She later left journalism to join her husband in Afghanistan for three years, whom she met the American University in Beirut. They left Kabul for the United States shortly before the invasion by the Soviet Union and remained there until the early 2000s

But “Bibi Gul” has never forgotten her pride in her first career.

Emmanuel Parisse is an AFP correspondent in Kabul

(AFP Photo / Shah Marai)

(AFP Photo / Shah Marai)