Letters from a mass murderer

OSLO, Sept 10, 2014 - The letter in itself is an anomaly. In the digital era, not many people send snail mail to AFP’s office in Oslo any longer. And a quick glance at the envelope is enough to identify the sender. The neat, clean handwriting in block letters is impossible to mistake for anyone else’s. It makes my blood freeze.

Over the course of one year, I have received three letters from Anders Behring Breivik, the right-wing extremist who killed 77 people in Norway on July 22, 2011. On that black day, he detonated a bomb near the government headquarters in Oslo and then went on to open fire on members of the youth wing of the Labour Party on the now infamous island of Utoeya.

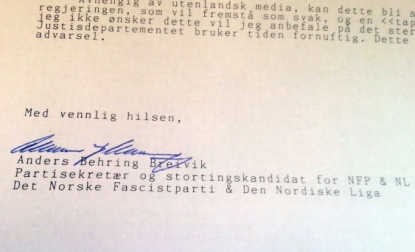

The letters are all typed. Only the address and the signature at the bottom are written by hand. They are long: The last of the three I received takes up seventeen A4 pages. I don’t reply. It’s a one-sided correspondence which prompts sympathetic colleagues to call me “pen pal” with one of the worst criminals in history.

(AFP Photo / Pierre-Henry Deshayes)

(AFP Photo / Pierre-Henry Deshayes)The first letter, received last year, is an endless tirade that I just skim through, choose not to process any further and quickly evacuate from my mind.

The second letter, in February, is rather more interesting. AFP is, apparently, the first to receive it (which, as I learn later, enrages the competition). Breivik lists a dozen demands, threatening that if they aren’t met, he will go on a hunger strike. One of the requests stands out: He wants a better game console than the one he has been given in prison.

Having covered the Breivik case since day 1 – that is, since the carnage on July 22, 2011 – I have always been struck by his skewed sense of proportions and his inability to distinguish the important from the truly trivial. When he was arrested on Utoeya after having just massacred 69 people, mostly teenagers, and physically and mentally traumatising hundreds of others, he asked the police to dress his aching index finger.

Video of truck bombing carried out by Breivik in Oslo on July 22, 2011. If you are unable to view it, click here.

In his letter, he demands a Playstation 3 to replace his PS2. He also raises other questions that are apparently slightly less deranged. He wants his prolonged isolation to end, and he wants officials to stop what he has referred to as “humiliating” near-daily body searches, which take place even though he is barred from pretty much any contact with the outside world. (Around the same time the police rejected his complaint against what he called "serious torture" in prison.)

I write a story that implicitly ridicules the Playstation request, believing that from now on I will receive no more "private" letters – until this new thick envelope with the same rigid and cold writing arrives at my office on September 5.

Rescuers look for bodies around the island of Utoeya July 23, 2011, the day after the massacre (AFP / Odd Andersen)

Rescuers look for bodies around the island of Utoeya July 23, 2011, the day after the massacre (AFP / Odd Andersen)Breivik is allowed to send letters from his prison cell, where he serves a maximum 21-year sentence that seems likely to be extended until the end of his life. But his letters are scrutinised by the prison authorities who censor anything that could be interpreted as incitement to crime. He is further constrained because he must pay for stamps and photo copies from the 300-kroner (36 euros) financial allowance he receives every week.

So, given these limits on his ability to communicate, why send these letters to AFP?

The trial of Anders Behring Breivik in Oslo City Court in August 2012 (AFP / Pool / Cornelius Poppe)

The trial of Anders Behring Breivik in Oslo City Court in August 2012 (AFP / Pool / Cornelius Poppe)Is it because his morbid attention to detail has prompted him to contact the media in alphabetical order? His meticulous approach was reflected in the fantasy world he described in great detail in his ideological manifesto sent just before the massacre and, most tragically, in the methodical way he killed his victims that day.

Is it because in addressing a large international agency, he knows that his words could potentially have a huge impact? In the pre-massacre manifesto, he writes that "90% of the world's news comes from just three agencies: Associated Press (USA), Reuters (UK) and Agence France Presse (France),” which, he laments, are “all supporting globalism and multiculturalism."

Or is it because he knows who I am? After all, he must have noticed me, sitting in the same seat in the front row just a few meters (yards) away from him during his ten-week trial in 2012.

Breivik at the opening of his trial, April 16, 2012 (AFP / Pool / Heiko Junge)

Breivik at the opening of his trial, April 16, 2012 (AFP / Pool / Heiko Junge)"I haven’t asked him," says his lawyer when I inquire by email. "I guess it is an overall assessment of how familiar the recipients (of his letters) are with the case and how able they are to understand and convey what he writes, combined of course with which readers (and how many of them) the individual journalist is able to reach.”

However that may be, the contents of the third letter are trickier. Unlike the previous one, it doesn’t deal with his conditions in jail, but focuses on politics. Over 34 pages, he explains that he wants to set up a "fascist" party, which is to carry on his fight by democratic means rather than through violence.

This raises a fundamental question: Should journalists disseminate the contents or not? AFP has chosen to do so, but with numerous precautions. The number of direct quotes from his letter is kept at a minimum, and the contents are contextualised. And I make a point of reminding the readers of the debate around his mental health which was central during the trial (the judges eventually found him criminally sane).

Obviously, in this type of situation journalists run the risk of being used and abused. Giving him a platform could help spread a message that remains as full of hatred as it was three years ago, when he cut dozens of young lives short. It could save him from the black hole of oblivion which many, especially in Norway, would like to see him consigned to for the rest of his life. Finally, and most importantly, it could reopen the still-recent wounds suffered by the victims’ families.

Self-portrayals: Breivik in various guises, posted on Facebook (right) and YouTube (the other four)

(AFP / Facebook / Youtube)

This is the view adopted by most Norwegian media. Breivik’s third letter has passed almost entirely unnoticed. The second letter did get some limited attention in Norway, mostly because of the bizarre request for a Playstation, but nothing like the interest it attracted abroad.

On the other hand, Breivik has undeniably left a mark on Norway. As a mass murderer who has consciously placed himself beyond the pales of civilised society, he has triggered a desire not to forgive but to understand. People want to know how peaceful Norway could give rise to such a monster. They want to know what that monster is made of.

Although what he calls his “conversion” to the rules of the democratic game comes far too late and his promises to renounce violence are probably worth less than the paper they are written on, the questions remain: Can a journalist really look away from this? Should Breivik’s “politics” be ignored, even though those precise ideas were the driving force behind his heinous acts?

Judging from the reactions I have received from readers, most opinions on this are set in stone one way or the other. I personally to this day do not know the answer.

Flowers on the shores of Utoeya Island on July 22, 2012 during an event to mark the first anniversary of the attacks by Anders Behring Breivik (AFP Photo / Daniel Sannum Lauten)

Flowers on the shores of Utoeya Island on July 22, 2012 during an event to mark the first anniversary of the attacks by Anders Behring Breivik (AFP Photo / Daniel Sannum Lauten)Pierre-Henry Deshayes is an AFP reporter based in Oslo.