Groping for truth of a murder in Istanbul

Istanbul -- When Jamal Khashoggi entered the Saudi consulate in Istanbul on October 2, I was neither watching or could have had any inkling this would turn into an event of any importance.

Yet his entry through its doors set off one of the most horrific and grotesque news stories I have handled in my nearly two decades as a journalist. And also one of the most delicate to handle.

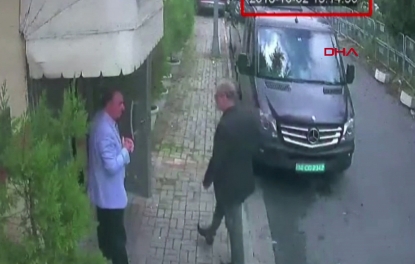

A video grab from CCTV footage obtained from Turkish news agency DHA shows Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi (R) arriving at the Saudi Arabian consulate in Istanbul on October 2, 2018.

(AFP / -)

A video grab from CCTV footage obtained from Turkish news agency DHA shows Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi (R) arriving at the Saudi Arabian consulate in Istanbul on October 2, 2018.

(AFP / -)The Khashoggi case has been unique in so many ways -- first and foremost because of the heart-wrenching tragedy of a man who walked into the consulate in the middle of a big city for routine paperwork and then never came out.

The details of the case -- a man strangled in a chokehold, his body dismembered with a saw and then reportedly dissolved in acid to leave no trace by a hit team flown in from Saudi Arabia allegedly on the orders of the country’s crown prince -- turned the stomach. And challenged us to use the most neutral and objective language to describe what had happened.

The events of that autumn afternoon sent shockwaves across the world, with consequences felt inside the White House, the presidential complex in Ankara and the royal palace in Riyadh.

Having worked the last 12 years in Iran, Russia and Turkey, I have covered a number of assassinations, each one with its own singular human tragedy and political consequences, such as the killing of Russian rights activist Natalya Estimirova in the northern Caucasus in 2009, the Turkish lawyer Tahir Elci in 2015 or the Russian ambassador to Ankara Andrei Karlov in 2016.

Yet the sheer, barely-imaginable horror of what happened to Khashoggi behind the doors of the consulate made this killing like no other I have covered. The alleged involvement of senior Saudi officials also added a colossal geopolitical dimension which could yet reshape the Middle East.

This image obtained December 11, 2018 courtesy of Time magazine shows one of four covers for Time magazine Person of the Year, with Jamal Khashoggi on the cover.

(AFP / Moises Saman)

This image obtained December 11, 2018 courtesy of Time magazine shows one of four covers for Time magazine Person of the Year, with Jamal Khashoggi on the cover.

(AFP / Moises Saman)But I also found this a uniquely disturbing news story to cover in that the truth has been elusive and exceedingly slow to emerge, sometimes obscured with false leads thrown up by the Saudi side.

The tortoise pace at which information emerged kept the story lodged at the top of the global headlines for weeks as the public eagerly awaited the actual truth. This meant that relatively small developments in Turkey -- a search of a car park or a Saudi-owned villa -- were propelled into the top news in the absence of concrete facts.

Even the tragic truth that Khashoggi lost his life inside the consulate was only confirmed days after his murder, with some still hoping a week after October 2 that he could still be alive.

In the beginning, I was deeply cautious, with the case of journalist Arkady Babchenko in Ukraine -- he was reported murdered only for him to emerge alive and well later in the day as part of a police sting operation -- still fresh in my mind. I tell myself always -- never make assumptions. But here, the worst-case scenario was the grim reality.

Perhaps I should not have been surprised by the slowness with which the truth over the Khashoggi case emerged, given this was a crime perpetrated by Saudi officials in a consulate inside Turkey.

An official stands at the door of Saudi Arabia's consulate in Istanbul, on October 23, 2018, during ongoing investigations into the killing of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi. (AFP / Yasin Akgul)

An official stands at the door of Saudi Arabia's consulate in Istanbul, on October 23, 2018, during ongoing investigations into the killing of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi. (AFP / Yasin Akgul)Saudi Arabia, one of the world’s most closed societies, initially covered up the crime with a host of false trails, notably that Khashoggi had left the consulate alive and well. It later turned out that this part had been played out by a body double who donned the victim’s own clothes.

But in the four and a half years that I have worked in Istanbul, I have also witnessed a tightening of the Turkish government’s control over the media under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Journalists have been arrested and many colleagues harassed on social media. The increased control has come largely not from direct state censorship but ownership changes that placed big media firms in the hands of pro-government holding companies.

This control has allowed the Turkish government -- with considerable skill -- to shape the media narrative in a case that has given Ankara considerable leverage over its Sunni Muslim rival Riyadh. And keen to keep the story moving with fresh details, we as journalists become to some extent willing players in this stage-managed operation.

In the first days, even weeks after the killing, regular, on-the-record statements from Turkish ministers and prosecutors were conspicuous by their absence. These usually come quite rapidly in Turkey in the case of a major criminal case such as a terror attack.

The unique circumstance that the killing had happened behind the closed doors of a diplomatic mission -- technically Saudi territory -- also meant there were no neutral witnesses.

Police members are pictured through a window inside the residence of the Saudi consul to Istanbul on October 17, 2018, as they investigate into the disappearance of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi at the kingdom's consulate in the city. (AFP / Ozan Kose)

Police members are pictured through a window inside the residence of the Saudi consul to Istanbul on October 17, 2018, as they investigate into the disappearance of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi at the kingdom's consulate in the city. (AFP / Ozan Kose)Instead, we have been forced to rely on our own sources, comments by lower-ranking officials and, above all, the pro-government Turkish media.

Most critical information about the case -- that Khashoggi was murdered by a team sent from Riyadh, that there is audio tape evidence, that his body was dismembered -- emerged first in the most staunchly Erdogan-cheering dailies Sabah and Yeni Safak.

This left us automatically reaching for the front pages of these newspapers first thing in the morning as the prime source of information.

There was more than a hint of irony about this, given that these papers have for the last years happily denounced foreign media, and even individual reporters, as agents of imperial Western plots against Turkey. Often, we had taken their front page stories with a hefty pinch of salt.

Yet here, often in the absence of other material to build a story around, we were often writing our daily wraps based on material in these newspapers.

Jamal Khashoggi at a press conference in the Bahraini capital Manama on December 15, 2014. (AFP / Mohammed Al-shaikh)

Jamal Khashoggi at a press conference in the Bahraini capital Manama on December 15, 2014. (AFP / Mohammed Al-shaikh)“Here is the Saudi execution team,” screamed the headline in Sabah on October 10, sensationally giving the identities and even photographs of 15 Saudis who it said had entered Turkey on a private plane specifically to murder Khashoggi.

Yeni Safak, which can be particularly needled by foreign media reports on Turkey, even printed a story on its front page crowing about how often it had been cited by international media including AFP.

The media tactics were evidently approved by Erdogan, who could now boast of being a champion of justice for a foreign journalist critical of authorities in his home country, despite being slated by rights organisations as a leading jailer of Turkish journalists critical of his rule.

The lack of regular information meant that official statements, when they came, had a massive impact. A speech by the president on October 23 finally giving detailed information generated more international interest than any other address by him that I can remember. Aware of this, the presidency even offered simultaneous translation into English and Arabic.

The head of the Saudi investigation into the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, Attorney General Sheikh Saud al-Mojeb (L) leaves the Saudi-Arabian consulate by car in Istanbul on October 30, 2018. (AFP / Bulent Kilic)

The head of the Saudi investigation into the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, Attorney General Sheikh Saud al-Mojeb (L) leaves the Saudi-Arabian consulate by car in Istanbul on October 30, 2018. (AFP / Bulent Kilic)Another major drop of details came on October 31 when Turkish prosecutors issued a written statement saying Khashoggi was strangled to death in a premeditated murder. The statement, almost a month after the killing, was issued after a visit by the Saudi prosecutor proved a fiasco.

It was a drip-drip of details occasionally interrupted by a sudden deluges of news. The flow of information has been deliberately and carefully choreographed with military precision by the Turkish authorities so only the information they want in the public domain gets there.

With no other witnesses and documentation, Turkey has been able to play the role of the neutral policeman and become the single credible source in news reports.

It has been an unwinnable struggle to cover this case and shed light on the truth of exactly what happened. For a truth there is, and this truth is known to people within the elite in Riyadh and maybe beyond. Even now, a full two months after the killing a frustrating list of questions remain. Who ordered the killing? How was the body disposed of? Was there a local middleman who assisted the Saudis? And will that audio tape ever see the light of day? Someone, somewhere, knows the full truth. Whether we will is another matter.

A protest sign reading Khashoggi way is seen across the street from the White House in Washington, DC, on December 23, 2018. (AFP / Andrew Caballero-reynolds)

A protest sign reading Khashoggi way is seen across the street from the White House in Washington, DC, on December 23, 2018. (AFP / Andrew Caballero-reynolds)