The end of the world

Santa Olga, Chili -- When we got to Santa Olga, a landscape of utter devastation greeted us. The town had been ravaged by the flames and no longer existed. It had been literally carbonized. We had covered plenty of wildfires before in Chile, but nothing compares to this.

These wildfires started in mid-January, in the center of the country. It was a toxic mix -- temperatures of around 38 degrees Celsius, violent winds, a few malicious acts and the forests were quickly engulfed in flames.

Santa Olga, January 27. (AFP / Martin Bernetti)

Santa Olga, January 27. (AFP / Martin Bernetti)We set off prepared -- a big 4x4, helmets, gas masks, plenty of water and thousands of kilometers stretching out ahead of us. The thick smoke hanging over the road quickly made us realize just how big these fires were.

After leaving Santiago in the morning, our first stop was the small town of Hualane, where residents were dousing their houses as they waited for the flames to arrive. The sky was yellow and ash was flying through the air.

San Ramon, January 26, 2017.

(AFP / Pablo Vera Lisperguer)

San Ramon, January 26, 2017.

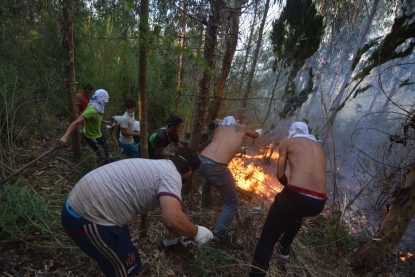

(AFP / Pablo Vera Lisperguer)Next stop -- Llico, where firefighters and villagers armed with buckets of water tried to extinguish the flames threatening homes, as a helicopter made round trips between the inferno and a nearby lake. Then San Ramon, where the sawmill was in flames. And then, finally Santa Olga, the end of the world, smoke still coming from the charred ground. By sunset, we had reached Constitucion; the sky was red and orange smoke covered the destroyed forests and houses on the horizon. It was a scene out of Armageddon.

We had planned the route we would take in Santiago, but changed directions in accordance with the fires’ progress. A colleague who remained behind in the bureau kept us updated of how they were progressing. There were also social networks, but these weren’t always reliable. More often than not it were the firefighters fighting the flames who pointed us in the right direction.

Chile has a national firefighting force, but it’s not part of any ministry and is mostly financed by donations. All firefighters in the country are volunteers, organized on a local level. Most of them are well equipped but they do not receive any compensation for the work they do. Whether they are available depends on whether their places of employment give them time off.

Pumanque, January 21, 2017.

(AFP / Martin Bernetti)

Pumanque, January 21, 2017.

(AFP / Martin Bernetti)One night, we accompanied two firefighters in a mutual exchange of favors -- we gave them a lift to the city of Constitucion and because we were giving them a lift, we were allowed to pass through a roadblock. We were going to spend the night in the city, while they were hoping to catch a bus back to Santiago -- they were afraid to stay away from work for too long.

Chile has a very strong culture of volunteers. Maybe to compensate for the weak presence of government in many areas of daily life. Covering these wildfires we met volunteers from all over the country, including the big cities. Their role was crucial in everything from cleaning up affected areas to helping protect homes.

Hualqui, January 27, 2017.

(AFP / Guillermo Salgado)

Hualqui, January 27, 2017.

(AFP / Guillermo Salgado)Access to these fires was fairly lax. Normally, when there is a major wildfire, police set up roadblocks. But this time around, there were relatively few. The area affected by the fire was huge and impossible to control completely. Locals often helped us, suggesting places where we could get a better look at the flames.

Some of the wildfires were caused by arson. On the ground, everyone talked about this. President Michelle Bachelet spoke of more than 40 people who had been detained in connection with the fires. But there was little agreement on the reasons for setting the flames. We heard everything from illegal land clearing, to land grabs and insurance scams. At the end of the day, noone knew for sure.

Santa Olga, January 27, 2017. (AFP / Martin Bernetti)

Santa Olga, January 27, 2017. (AFP / Martin Bernetti)Natural catastrophes are often difficult to cover, but wildfires are among the most dangerous because the fire is so unpredictable. In a few seconds, it can change direction and entrap you. We work with a mask and protective glasses and are always aware of the danger. So if we go down a trail into the forest to film the flames, better to leave the car pointing in the right direction (out) so that you could make a quick getaway.

There were times when we found ourselves driving along a highway at night, with fires on either side of us. We joked that a zombie could appear from the flames at any moment. But we weren’t very comfortable -- the fires were merciless in their destruction and the heavy smoke was everywhere. That was probably the image that will remain with us -- the infernos, stretching for kilometers in the darkness.

Santa Olga, January 25, 2017. (AFP / Pablo Vera Lisperguer)

Santa Olga, January 25, 2017. (AFP / Pablo Vera Lisperguer)Wildfires can be frequent in Chile. Often they break out near the second city of Valparaiso, partly because it is surrounded by hills, and has lots of wildcat houses to accommodate an ever-growing population. We covered a huge wildfire there in 2014 and another one a year later. We were there earlier this year. But these wildfires were at an edge of a city.

This time around, we found ourselves in the middle of countryside, with a huge surface for the flames to devour.

Llico, January 27, 2017.

(AFP / Martin Bernetti)

Llico, January 27, 2017.

(AFP / Martin Bernetti)First estimates, on January 22, said that 90,000 hectares of forest had been affected. Less than a week later that area had grown to half a million hectares and 11 dead and the government had declared a state of emergency.

One of the most striking things was the resilience of the locals. They were used to hard knocks from life. They rarely get angry, but just get on with it. The locals always greeted us warmly, often asking us to pass on thank you messages or to ask for help.

Santa Olga, January 26, 2017.

(AFP / Pablo Vera Lisperguer)

Santa Olga, January 26, 2017.

(AFP / Pablo Vera Lisperguer)Out of all that we saw, one of the most striking images will be that of Santa Olga, that town of several thousand that was left completely devastated. We went there two times during the fires.

The first night, we had a sense that we had reached the end of the world. Everything had been burned. There were only a few residents in the middle of the ashes and the smoke. “It’s like an atomic bomb,” they told us. Many of them had already lost homes in the earthquake that struck the country in 2010.

Concepcion, January 28, 2017.

(AFP / Guillermo Salgado Sanchez)

Concepcion, January 28, 2017.

(AFP / Guillermo Salgado Sanchez)Santa Olga was a small, poor town. And now its residents lost the little that they had. It’s never the houses of the rich that disappear, it’s always those of the poor.

This blog was written with Pierre Celerier and translated by Yana Dlugy in Paris.

The view in Santiago, January 20, 2017. (AFP / Martin Bernetti)

The view in Santiago, January 20, 2017. (AFP / Martin Bernetti)