In the depths of the Amazon

Waiapi Amazon tribal territory, Brazil -- There’s a point, whatever corner of the world you’re traveling in, when you may have that urgent question: where’s the toilet? But at the start of a rare visit to Waiapi tribal territory deep in the Amazon, the question we had was more nuanced: what even was the toilet?

The Waiapi tribe only came into contact with the outside world in the 1970s and they’ve worked hard to preserve their way of life. Dressed in red loincloths and covered in red urucum and black jenipapo dyes, they still subsist entirely on hunting, fishing and small-scale slash-and-burn farming in Brazil’s teeming rainforest.

Brazilian Waiapi walk on the road of the Waiapi indigenous reserve, at Pinoty village in Amapa state in Brazil on October 12, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)

Brazilian Waiapi walk on the road of the Waiapi indigenous reserve, at Pinoty village in Amapa state in Brazil on October 12, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)An AFP team of three, we arrived in a big white 4x4 after driving most of a day on increasingly rough roads. Unloading our massive collection of cameras, computers, insect repellent, waterproofs and other gear under the eye of a half dozen shy village children wearing almost nothing, it was clear we had a little adjusting to do.

Then came that urgent question and a Waiapi leader, resplendent in beads and body paint, pointed us down a mud track through the jungle to a shallow river, where he left us.

We surveyed these Waiapi "toilets" in considerable puzzlement.

In one part of the river, children wearing small versions of the ubiquitous red cloth splashed about in knee deep water. A short distance away in the middle of the stream rose a table-sized wooden platform.

The mysterious platform. (AFP / Marie Hospital)

The mysterious platform. (AFP / Marie Hospital)Were you meant to squat on the platform? Go in the woods at the edge? Do it all in front of an audience?

Baffled and too embarrassed to get the bottom of that particular story we retreated.

Adjusting was going to take a bit longer perhaps.

Geographically speaking, the Waiapi are not as isolated as it might seem.

A small Brazilian town called Pedra Branca is just two hours away by bumpy, unpaved road. The Amapa state capital Macapa, which we reached by flying much of the night on two planes from Rio de Janeiro, is only three or four hours’ drive further.

But the tribe has campaigned hard to prevent outsiders from crossing those short distances – and with good reason.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)

(AFP / Apu Gomes)Their first contact with whites in the 1970s introduced diseases like measles that almost wiped out the Waiapi, who lacked immunity, let alone vaccines. Today, they’re back up to 1,200 people but face a new threat: industry friendly President Michel Temer’s bid to open the surrounding nature reserve to foreign gold and other mineral mining companies.

Temer’s plan, which he later suspended under pressure from environmentalists, was the reason AFP planned this trip. We wanted to give a voice to the indigenous people who have been living here since long before the first Europeans landed in South America.

As pressure from loggers, miners and industrial farmers mounts every year against the Amazon, tribes like the Waiapi are popularly portrayed as guardians over the “lungs of the planet.” Yet the outside world rarely hears directly from them.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)

(AFP / Apu Gomes)At our AFP office about 1,800 miles (2,900 km) away in Rio de Janeiro, obviously the first thing we did was check out Google maps. All the map showed was a road snaking north through solid green, before stopping abruptly and intriguingly in the middle of the jungle under the word “Waiapi.”

Next, we began calling around to ask how to arrange the trip, querying environmental activists, state bodies dealing with forestry protection and indigenous rights, adventurous friends…

The good thing for journalists in Brazil is that contacts, including bureaucrats, are generally very friendly. What’s not so helpful is that they also have a tendency – in the most friendly way possible – to promise the world, then disappear without delivering.

For several weeks, we hacked through this forest of officialdom. We were trying to get permission to visit a people who live without electricity, much less cellphones and computers, but our tools were modern: email, Whatsapp, phone, Skype, Facebook.

The final negotiations were made with Apina, a council set up by the Waiapi in the 90s to organize the demarcation of their territory (a vital step in keeping out unwanted visitors). They used a VHF radio to clear our request with village chiefs scattered in the forests and finally the green light – in the form of an impressively formal letter from Apina – came through.

Even after traveling up to Pedra Branca, there was a nerve-wracking moment when it seemed we might not make it.

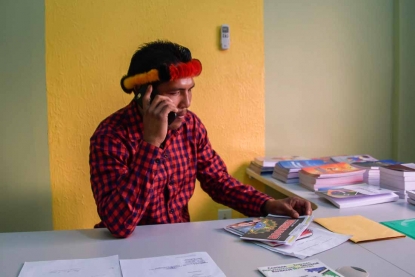

Our contact in the town was a remarkable Waiapi tribesman Jawaruwa. Last year, Jawaruwa joined the Pedra Branca city council, becoming the first member of his people to win a Brazilian electoral post, and he was keen to help.

Jawaruwa Waiapi, city councilman of Pedra Branca do Amapari city, works at his office, in Amapa state in Brazil, on October 12, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)

Jawaruwa Waiapi, city councilman of Pedra Branca do Amapari city, works at his office, in Amapa state in Brazil, on October 12, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)But we were just about to set off in our 4x4 with Jawaruwa when a text message came in that someone had been shot in one of the villages.

There had been terrible stories in recent months of illegal gold prospectors murdering indigenous people, as well as gunmen linked to big landowners slaying poor, non-indigenous farmers who got in their way.

So we feared the worst. If this was an attack by outsiders, there’d be huge tension and our journey would be cancelled.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)

(AFP / Apu Gomes)Luckily, we’d established a good rapport with Jawaruwa and he listened to our pleas for not abandoning the assignment. The worry on his face was impossible to hide (he explained that the death of one Waiapi feels like losing a family member for the whole tribe), but we reassured him that we were used to working in sensitive situations.

“We can try to drive in and see,” he said, “but if people are too upset they won’t let you enter and we’ll have to turn around.”

That was as much as we could ask for.

We headed off in our big 4x4 down a road that seemed to part an ocean of soaring trees, wondering at every corner what we’d find.

Tribal chieftain Tzako Waiapi.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)

Tribal chieftain Tzako Waiapi.

(AFP / Apu Gomes) Tribal chieftain Tzako Waiapi plays the flute in the morning at the Manilha village in Waiapi indigenous reserve in Amapa state in Brazil on October 14, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)

Tribal chieftain Tzako Waiapi plays the flute in the morning at the Manilha village in Waiapi indigenous reserve in Amapa state in Brazil on October 14, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)

At a small wooden bridge, a sign appeared reading “Protected land.”

“Stop here,” said Jawaruwa, still in his city clothes of jeans and neat shirt, but wearing a beautiful feather headdress.

The silence after we got out of the car was overwhelming. Gradually it gave way to hoots of birds and the mechanical-sounding, rhythmic mass buzz of insects.

It was then that we saw them: about 20 Waiapis, naked except for loin cloths, emerging from the trees.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)

(AFP / Apu Gomes)These days, journalism is increasingly managed by the people journalists try to report on.

Great, original reporting still happens of course: AFP’s global network, for example, is regularly able to explore corners of the world that others fail to reach. But in general, the public relations people, communications specialists, information officers, minders, goons – different descriptions for different settings, but all folk basically sharing the same goal of controlling the media – are on the ascendant.

So this meeting in the jungle was stunning for reasons beyond the aesthetics of those bright red cloths appearing from a wall of green.

The three of us looked at each other, eyes wide, all thinking the same thing: “This is real.” Jawaruwa told us to walk on forward.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)

(AFP / Apu Gomes)By now, it had been clarified that the shooting was just a hunting accident. The victim would survive, frayed nerves had settled, and we were going to be able to stay.

We were excited. While a handful of other journalists had managed to visit the Waiapi before us, we got something that our colleagues hadn’t been so lucky with: time. Previous visits had been fleeting, but the tribe said we could now stay four days.

Of course, even four days still meant basically scratching at the surface.

We were never going to get more than a passing understanding of the Waiapi spiritual system, in which a host of rather volatile sounding spirits inhabit trees and animals. We never had time to follow them hunting, although we did enjoy fish and rather tasty, if horrific looking smoked monkey brought in from the forest. And our Waiapi language skills didn’t get much beyond “thank you.”

But we were incredibly fortunate all the same.

Simply by hanging out, watching daily life, sleeping in hammocks under the thick stars of an unpolluted sky, and drinking the Waiapis’ oddly wonderful cassava beer potion “caxiri,” we'd manage to catch a glimpse of completely alternative world.

Sky above the Amazon.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)

Sky above the Amazon.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)Sometimes news reporting, even on hugely consequential stories, may pivot on getting no more than a single key quote. The dedicated journalist will do anything – stay up all night outside someone’s door; harass a spokesman for hours; beg, cajole and charm sources – to get it.

A trip like this, however, requires a different skillset.

From the moment we arrived in the village we were bombarded with novelties: every painted face, every group of people sitting around a fire, every child running barefoot was a picture, video or potential text interview. We were in a journalist’s version of the candy store.

Jawaruwa Waiapi and his family walk amidst fog, early in the morning, at the Manilha village in the Waiapi indigenous reserve in Amapa state in Brazil on October 13, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)

Jawaruwa Waiapi and his family walk amidst fog, early in the morning, at the Manilha village in the Waiapi indigenous reserve in Amapa state in Brazil on October 13, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)The challenge wasn’t eking out that one quote, but coming up with a plan to sort this cornucopia into distinct stories – and, given our ignorance about the Waiapi, being ready to change that plan.

One thing we quickly had to accept was that not everything was as it first seemed.

So the initial image of bare chested warriors with six-foot long bows and arrows was not false. The Waiapi are truly skilled hunters and masters of finding everything needed to survive – from housing to medicine and weapons – in the forest.

But we became aware of surprisingly modern elements seeded into this ancient lifestyle.

For example, one or two villagers had mobile phones, using them to take pictures, since there is no signal.

The elder son of the chief had a rickety old TV set and a satellite dish by the thatched roof where he slept, although we never saw it functioning. The younger son, a big guy who proudly paraded about with a wooden club, had what was apparently pretty much the only Waiapi car – even if it had no gasoline at the time and the nearest gas station was away in Pedra Branca.

Waiapi children watch a video of a traditional Waiapi dance in a mobile phone at the Manilha village at the indigenous reserve Waiapi in Amapa state in Brazil on October 12, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)

Waiapi children watch a video of a traditional Waiapi dance in a mobile phone at the Manilha village at the indigenous reserve Waiapi in Amapa state in Brazil on October 12, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)And yes, even if Waiapi elders are strict in enforcing their culture, tribal members do visit Pedra Branca. They are experts at navigating between what can resemble two alternate realities.

When we gave a ride to town to one young man, we paused on the outskirts of the town so that he could switch from loincloth to jeans, polo shirt and leather shoes by the side of the road. We watched Jarawawa undergo this metamorphosis in reverse, shedding his city clothes when he arrived in the rainforest to reemerge almost naked, covered in red dye – and rather more relaxed.

Talking of cars, it must be said that while the Waiapi generally get about on foot, happily walking long distances between villages or hunting grounds, they were delighted at the availability of our 4x4 which turned into an informal jungle taxi service. Sometimes almost a dozen would find a way to cram in.

(AFP / Marie Hospital)

(AFP / Marie Hospital)But perhaps the most surprising aspect was the ease that the tribe's members felt in front of our cameras and notebooks. We’d worried they would be hesitant to talk, yet they seemed to grasp immediately what we wanted in terms of getting each story –- something you tend to see in media veterans who can practically spoon feed journalists.

At one settlement, a dozen inhabitants made a beeline for Marie’s video camera, shaking arrows and yelling in a mini anti-Temer demonstration that wouldn’t have looked out of place in front of a government building, but instead was being performed just for us in the depths of the Amazon.

Jarawawa, who obviously has extra experience as an elected local politician, even had the media savviness to pick up on the fact that we were noticing the amount of work left to women in the main village where we slept.

Actually, it was impossible for us not to notice: women tended the fires; women hiked to harvest the cassava, then labored for hours to turn it into beer; and women, or often young girls, cared for the numerous babies.

One of these tough women was disarmingly frank. “No,” she said when Marie asked her if she was happy.

This combination of pictures shows portraits of (L to R up) Suwerika Waiapi, Eriana Aromaii and Sykyry Waiapi; (L to R down) Kurija Waiapi, Ruwana Waiapi and Siurima Waiapi at the Waiapi indigenous reserve in Amapa state, Brazil on October 14, 2017. (AFP / Apu Gomes)

This combination of pictures shows portraits of (L to R up) Suwerika Waiapi, Eriana Aromaii and Sykyry Waiapi; (L to R down) Kurija Waiapi, Ruwana Waiapi and Siurima Waiapi at the Waiapi indigenous reserve in Amapa state, Brazil on October 14, 2017. (AFP / Apu Gomes)But Jarawawa came on his own initiative later to point out that men do the hunting and the clearing of trees for the slash-and-burn plots. On cue, a group of men marched off with axes to do some tree chopping – and we were invited to tag along.

More than anything this flexibility showed that the Waiapi are great survivors.

They absorb just enough modern developments – including inviting in media like us – to defuse the pressure from the outside world, while actively working to guard nearly all their other traditional ways.

It’s a far more sophisticated approach than just hiding in the forest, as some of the few remaining uncontacted tribes do.

The Waiapi left us free to wander around as we liked. They don’t seem to have much structure to their day, other than getting up with the sun and getting into their hammocks at dark.

Waiapi men enjoy the Feliz river in the Waiapi indigenous reserve in Amapa state in Brazil on October 14, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)

Waiapi men enjoy the Feliz river in the Waiapi indigenous reserve in Amapa state in Brazil on October 14, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)We rarely stopped interviewing or getting images, but when the three of us sat down at an open fire to eat or to brew the instant coffee and powdered milk we’d brought from town, we’d fall to discussing our more personal feelings about this unusual trip.

Apu told us how his great grandmother was from an indigenous tribe and had been stolen as a child from a village, then eventually married into a white family. He considers himself as Brazilian as the next person, but has roots in people who maybe once lived much like the Waiapi.

The connection added a bitter sweet element for Apu and got us all thinking about Brazil’s tragic history of dealing with its indigenous peoples – and the Waiapis’ odds for survival in the longer term.

We even questioned whether our own visit – ostensibly doing good by providing information about a people that Brazil’s powerful pretty much ignore – wouldn’t end up contributing to the tribe’s demise.

Portrait of a Waiapi child in the Waiapi indigenous reserve in Amapa state in Brazil on October 12, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)

Portrait of a Waiapi child in the Waiapi indigenous reserve in Amapa state in Brazil on October 12, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)Here’s just one example.

We were constantly admiring how the Waiapi live with almost zero waste, keeping disconnected from our industrial, consumerist world. So they use calabash gourds and thin pieces of cane as natural cups and straws. They use tapioca pancakes to put food on – plates you can eat.

But when it came time to leave, the women eagerly took our empty, big plastic bottles. Same thing with our little collection of plastic plates and forks.

We felt guilty. The ugly bottles and plates didn’t look right in that setting, but can you really deny people something as practical as plastic when it becomes available?

Around the campfire, our talk also inevitably turned to more down-to-earth – even if equally hard-to-answer – questions.

Chieftain Japarupi Waiapi shows a roasted monkey -part of Waiapi's diet, also based in Manioc and fruits- at the reserve in Amapa state in Brazil on October 13, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)

Chieftain Japarupi Waiapi shows a roasted monkey -part of Waiapi's diet, also based in Manioc and fruits- at the reserve in Amapa state in Brazil on October 13, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)Like that whole Waiapi toilets mystery.

So the good news is that after some dogged investigating we did figure out how the river worked.

There were actually two rivers running near the village. The shallow one with the wooden platform was for answering the call of nature, while a second, much deeper one was for swimming and bathing, which the Waiapi take very seriously.

The wooden platform, however, was not for what we imagined – it was for clothes washing. Imagine the scandal we dodged there. And the fact that small kids splashed around in that same water was also normal, because the toilet part was actually reserved for about 20 meters downstream.

Simple, really.

“You go in the middle of the river, do your business and clean yourself with the water,” Jawaruwa explained. No toilet paper needed – another plus for the Waiapis’ green lifestyle.

Waiapi men dance and play flute during the Anaconda's party -during which they make flutes to play and dance, and at the end leave all flutes on the river for the Anaconda snake to protect their village- in the Waiapi indigenous reserve in Amapa state in Brazil on October 14, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)

Waiapi men dance and play flute during the Anaconda's party -during which they make flutes to play and dance, and at the end leave all flutes on the river for the Anaconda snake to protect their village- in the Waiapi indigenous reserve in Amapa state in Brazil on October 14, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)OK, but there was still the puzzle of how you were meant to do this in any kind of privacy, what with the splashing children, potential clothes washing activity, and the chance that someone else, or even several others, might feel a need to come down to the river toilet at the same time.

On sharing his concerns with the village chief, Sebastian was given a guard detail of two young tribesmen in red loincloths to cordon off the river access, as if he were some kind of rainforest celeb. But having two grinning kids standing watch wasn’t any better, a downcast Sebastian reported back, and the mission was aborted.

From then, we reserved these delicate moments for the starry night hours or furtive daytime dashes into the bushes, wondering if there were dangerous animals about and feeling every bit like the clumsy gringos that we were.

A Waiapi toddler at the Manila village at Waiapi indigenous reserve in Amapa state in Brazil on October 14, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)

A Waiapi toddler at the Manila village at Waiapi indigenous reserve in Amapa state in Brazil on October 14, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)There was much we’d never understand about the Waiapis – and vice versa.

Still, the day we all said goodbye, surrounded by those wonderful trees and the din of birds and insects, there was genuine affection between us and our hosts.

We came from two very different worlds, but we'd managed to understand one important thing at least: we share the same planet and need each other.

(For more information on the Waiapi, read the stories from this reporting trip: For Amazon tribe, Amazon is a whole world; Beer o'clock in the Amazon; Tribe sharpens arrows against Amazon invaders.)

A Waiapi man uses his bow and arrow at the Pinoty village at the Waiapi indigenous reserve on Amapa state, in Brazil, on October 12, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)

A Waiapi man uses his bow and arrow at the Pinoty village at the Waiapi indigenous reserve on Amapa state, in Brazil, on October 12, 2017.

(AFP / Apu Gomes)