Welcome (back) to Hell: war in Ukraine reopens Sarajevo’s scars

The invasion of Ukraine has brought back painful memories for those who lived through the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina, the bloodiest in Europe since World War II. Thirty years on, the trauma is still raw, writes Sonia Bakaric, who covered the conflict for AFP

PARIS – Thirty years have passed since the start of the war in Bosnia, but I can never forget its brutality. The memories have come alive again with the war in Ukraine, where civilians are suffering in the same ways they did back then in the most murderous of the conflicts that followed the collapse of the former Yugoslavia.

Kyiv is not much more than an hour’s flight from Sarajevo, which suffered the longest siege in modern history.

Columns of refugees have returned to Europe, as scared and exhausted faces again flee shelling and air strikes that spare neither schools nor hospitals. The same desperate cries for help from people sheltering in their basements are being heard. The hell that was visited on Bosnia is now being inflicted on civilians in besieged Ukrainian cities like Mariupol.

Sarajevo town hall lit up in the colours of the Ukrainian flag on February 24, 2022, the day Russia invaded the country (AFP / Elvis Barukcic)

Sarajevo town hall lit up in the colours of the Ukrainian flag on February 24, 2022, the day Russia invaded the country (AFP / Elvis Barukcic)

Memories of the spring of 1992 when Bosnia-Herzegovina decided to break away from what was left of Yugoslavia keep coming back.

At the time, everyone was gripped by fear that if war came to Bosnia, it would be even worse than it had been in Croatia which had broken away the previous year. With the Yugoslav National Army (JNA) supporting Bosnian Serbs, the nightmare of large-scale massacres in this multiethnic land where Muslims made up 43 percent of the population, Orthodox Serbs 33 percent and Catholic Croats some 17 percent, was all too real.

The overwhelming majority of Bosnian Serbs did not want Bosnia to become independent. But Muslims and Croats would no longer be ruled from the Serbian capital Belgrade. With many people in mixed marriages, families would be ripped apart.

Serb artillerymen on the frontline during the battle for Vukovar in Croatia on October 5, 1991 (AFP / Marja Illic)

Serb artillerymen on the frontline during the battle for Vukovar in Croatia on October 5, 1991 (AFP / Marja Illic)

Serb troops only 40 kilometres (25 miles) from the Croatian capital Zagreb on July 4, 1991 (AFP / Joel Robine)

Serb troops only 40 kilometres (25 miles) from the Croatian capital Zagreb on July 4, 1991 (AFP / Joel Robine)

I had just graduated in international and European law from the Sorbonne in Paris. Brought up in France in a family which came from Croatia on one side and Bosnia on the other, I decided to move to the Croatian capital Zagreb to work as a freelance journalist. I joined AFP there in 1993, working in what effectively became its hub for the former Yugoslavia for seven years.

I reported from many bombed and battered towns and cities, from Petrinja, Osijek and Nustar in Croatia to Mostar, Bihac and Sarajevo in Bosnia-Herzegovina. I can still see my mother’s family and my friends in Bosnia repeating over and over that the war would be worse there, even as they clung to the hope they would be spared.

I knew they were right to worry and I was afraid for them. The luminous beauty of the Bosnian valleys of my childhood ablaze with plum blossoms was no comfort. We held our breath. The news coming out of the old wooden radios across Bosnia that spring was more and more worrying. The television newsreaders looked graver by the day as the world’s media began sending “special correspondents” to Bosnia.

Serb forces near Knin in southern Croatia in February 1993 (AFP / Gabriel Bouys)

Serb forces near Knin in southern Croatia in February 1993 (AFP / Gabriel Bouys)

The war started on April 5, 1992, the day the people of Sarajevo took to the streets to plead for peace. That day I was with my family close to Tuzla in northeastern Bosnia, around 100 kilometres away. Lots of their Serb neighbours had already left. The same had happened in Croatia, and it was not a good sign. I remember taking medicine to my sick grandmother just in case war did break out.

A Serb airstrike on Sarajevo, on June 5,1992 (AFP / Georges Gobet)

A Serb airstrike on Sarajevo, on June 5,1992 (AFP / Georges Gobet)

The march for peace in Sarajevo – the city where the spark that started World War I was lit – began to grow both in size and emotion as the day wore on, and the Yugoslav flag was trampled underfoot. Groups of hooded Serb men were already putting up barricades, and the spectre of what was to come became clearer.

The first two victims of the war died that afternoon – two women, Suada Dilberovic a Muslim and Olga Sucic a Croat. They were cut down by snipers, for which Sarajevo would soon become notorious, raining down death from the hillsides around the city.

Bosnian special forces respond to Serb snipers who fired on peace marchers in Sarajevo in early April 1992 (AFP / Mike Persson)

Bosnian special forces respond to Serb snipers who fired on peace marchers in Sarajevo in early April 1992 (AFP / Mike Persson)

A world collapsed. Panic and fear. Then came the shelling from the encircling Bosnian Serb forces. Those who refused to take sides tried to get out. “We don’t know where we are going to go,” my Serb friends, with whom we passed the summer on Croatia’s Adriatic coast, told me. I never saw them again. They were the last telephone calls of our life before.

The siege of Sarajevo began less than a month later on May 2. It would last 1,425 days – the longest in modern history. Sarajevans were caught like mice in a trap and began taking to the shelters. That day local TV broadcast their first dramatic live telephone interview with Bosnia president Alija Izetbegovic, who was being held in a barracks of the Serb-controlled Yugoslav army, the JNA. The next day its soldiers tried to take the presidential building in their first major push to take the city, which was beaten back.

Sarajevo's Twin Towers on fire in on June 8, 1992 (AFP / Georges Gobet)

Sarajevo's Twin Towers on fire in on June 8, 1992 (AFP / Georges Gobet)

Sarajevo’s mix of Muslims, Croats, Serbs and Jews had always muddled along together peacefully, and their city was adored for its Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian architecture and the generosity of its people. But its 350,000 inhabitants were now cowering under a deluge of shrapnel and steel. The siege would last three times longer than that of Stalingrad.

The Bosnian Serb forces were led militarily by Ratko Mladic and politically by Radovan Karadzic, a psychiatrist whose poems had fantasised about a “Sarajevo in flames”, describing its destruction as almost a religious experience. “The town burns like a piece of incense,” he wrote.

Ratko Mladic (left) and Radovan Karadzic on August 5, 1993 in Pale, the Serb town from which the siege of Sarajevo was directed (AFP / Michael Evstafiev)

Ratko Mladic (left) and Radovan Karadzic on August 5, 1993 in Pale, the Serb town from which the siege of Sarajevo was directed (AFP / Michael Evstafiev)

Just like Mariupol in Ukraine, the city was deprived of water, food, electricity and medical supplies while the Serb forces rained down shells and mortars from the surrounding hills. When I hear Ukrainians now talk about what they are suffering, they feel like distant cousins, their experience is so close to what the victims of the wars in the former Yugoslavia suffered.

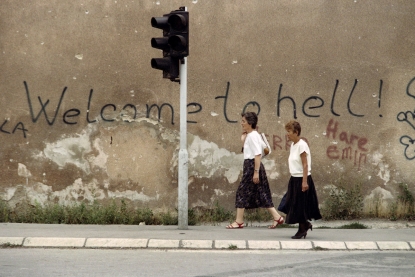

“Welcome to hell!” someone wrote on a wall in Sarajevo a year into the siege, and it said everything about the nightmare in which 11,514 people lost their lives and another 60,000 were wounded.

'Welcome to Hell!': Grafitti on 'Sniper Alley' Sarajevo on August 24, 1993 that later became iconic of the siege (AFP / Gabriel Bouys)

'Welcome to Hell!': Grafitti on 'Sniper Alley' Sarajevo on August 24, 1993 that later became iconic of the siege (AFP / Gabriel Bouys)

Piled-up carcasses of bullet-riddled cars became fragile ramparts to cower behind for those who had to venture out to get food or fuel. Sheets were strung across Marshal Tito Street to hide people darting from one side to the other from the eyes of the snipers.

First summer of the siege: Sarajevo June 24,1992 (AFP / Christophe Simon)

First summer of the siege: Sarajevo June 24,1992 (AFP / Christophe Simon)

Humanitarian aid was erratic despite an air bridge being opened up to the city. It became an umbilical cord linking Sarajevo with the rest of the world. But the flights would often be blocked by the Serbs. Meanwhile in the besieged city, women exhausted themselves inventing recipes that contained fewer and fewer ingredients.

I remember the “pita” (bread) confected from potatoes and pies made from a rice porridge dotted with wild herbs picked from the city’s parks and gardens. And then there were the “meatballs” that consisted of breadcrumbs mixed with onion and water, or the fake coffee made from roasted roots. These were great humiliations for a population that had prided itself on laying on groaning tables of local specialities for guests.

Children, who should have been playing, had a hard look in their eyes, nor is it easy to forget the anguish of their grandparents deprived of the medicine they needed to treat chronic illnesses.

A child hunkering behind a car playing with water in a puddle in Sarajevo on August 23, 1993 (AFP / Gabriel Bouys)

A child hunkering behind a car playing with water in a puddle in Sarajevo on August 23, 1993 (AFP / Gabriel Bouys)

Many people were killed by snipers going to get water from the standpipes or tankers, their bodies hastily dragged into the backs of cars and rushed at breakneck speed to hospital morgues.

A woman struggles through a Sarajevo snowstorm on March 26,1993 (AFP / Vincent Amalvy)

A woman struggles through a Sarajevo snowstorm on March 26,1993 (AFP / Vincent Amalvy) Men dragging wood through a dangerous part of 'Sniper Alley' in Sarajevo on August 31, 1993. (AFP / Gabriel Bouys)

Men dragging wood through a dangerous part of 'Sniper Alley' in Sarajevo on August 31, 1993. (AFP / Gabriel Bouys)

Sarajevo’s glacial winters – it hosted the Winter Olympics in 1984 – added further to the suffering, with people forced to burn their books when they ran out of wood. The shortages got so bad some of the dead had to be buried in wardrobes, sometimes under Serb shelling, many in an old Olympic site where the graves seemed to sprout as far as the eye could see.

The siege of Sarajevo snuffed out the lives of the poor and the rich alike, intellectuals, workers, teachers, women and children. With Bosnia hit by an arms embargo, men who had become soldiers to fight what was then one of the most powerful armies in Europe, died in their droves.

All the while Sarajevans appealed for international help, and could not believe the “civilised” world was not able to put an end to the massacre.

A United Nations helicopter and tank vehicle close to Tuzla airport in Bosnia (AFP / Pascal Guyot)

A United Nations helicopter and tank vehicle close to Tuzla airport in Bosnia (AFP / Pascal Guyot)

Every day could be your last, and for many staying alive was an act of absolute resistance. Trying somehow to remain a little chic despite everything was also an act of defiance for many women.

Keeping up appearances: Two young women make a dash across a Sarajevo street notorious for snipers (AFP / Pierre Verdy)

Keeping up appearances: Two young women make a dash across a Sarajevo street notorious for snipers (AFP / Pierre Verdy)

With no beauty products, they used fish oil and anti-burns ointments to make face creams or would dab on their last drops of olive oil. A lucky few used old eyeliner pencils for a bit of shadow. Mint leaves were boiled with baking soda to make deodorant.

Bosnia was not spared on any front. The Serbs launched an horrific campaign of ethnic cleansing — men shot on their doorsteps in front of their families, village after village burned, massacre after massacre.

A man tends to a woman injured in a Serb mortar attack in the back of a car in Sarajevo on June 27, 1992 (AFP / Christophe Simon)

A man tends to a woman injured in a Serb mortar attack in the back of a car in Sarajevo on June 27, 1992 (AFP / Christophe Simon)

The land grab was meant to create a “Greater Serbia” with all the territory they had taken in Bosnia and Croatia to be also ruled from Belgrade. But it never happened and the fevered nationalist dream was left in tatters.

The Serbs in these “cleansed” areas ended up living like 19th-century peasants without running water or electricity, utterly dependent on international aid, and without their old friends and neighbours from other ethnicities who had been killed or forced to flee.

Another “war within a war” broke out between Bosnian Croat forces, backed by Zagreb, and the majority-Muslim Bosnian government army in 1993. Civilians were again the victims of terrible atrocities with Mostar’s old Stari Most bridge, a jewel of Ottoman architecture, destroyed by Croat shells.

A temporary bridge in Mostar, Bosnia, over the spectacular span previously bridged by the destroyed Stari Most on December 17, 1995 (AFP / Pascal Guyot)

A temporary bridge in Mostar, Bosnia, over the spectacular span previously bridged by the destroyed Stari Most on December 17, 1995 (AFP / Pascal Guyot)

Bosnia continued to be dismembered. I can still see the rural population fleeing for their lives or the images of skeletal prisoners from the Serb detention camps like the one in Omarska, that made front pages around the world.

The fighting went on until the genocide at Srebrenica, where more than 8,000 Muslim men and boys were killed when the Serbs took the town, which was supposed to be under United Nations protection. It was Bosnia’s bloodiest chapter.

The war to me was like a never ending visit to the cemetery. I lost family and friends, and some I knew disappeared without trace. Like the friends who were badly wounded near Sarajevo were evacuated to God knows where. Others went into exile in Canada or Australia to avoid being ordered to kill a neighbour or childhood friend. My paternal family in Croatia also lost people.

A Croat soldier comforts an old woman whose house had been destroyed in a Serb air raid in Croatia on September 26, 1991 (AFP / David Brauchli)

A Croat soldier comforts an old woman whose house had been destroyed in a Serb air raid in Croatia on September 26, 1991 (AFP / David Brauchli)

At the time, journalists would just jump on a plane to cover a conflict without any training about how to work in a war zone. Some freelancers took out all their savings so they could cover the first major conflict in Europe since World War II.

As in Ukraine, AFP covered the wars from start to finish, constantly relieving its teams. However, we almost had no helmets or bulletproof jackets. And those that had often refused to wear them because at the time they were too heavy to run in. Reporters were also ill at ease wearing bulletproof vests to interview civilians who had no protection at all.

We would write out TV or Press with white tape on our cars. As protection goes, it was pretty illusory, like shouting “Don’t shoot!” There were no mobile phones then, so we sometimes had to go long distances to dictate our reports down the phone from a hotel or a post office. The internet did not exist either, and rolling news channels were rare, with most reports going out on the evening news.

TV crew running for cover in Sarajevo, on May 31, 1992 (AFP / Georges Gobet)

TV crew running for cover in Sarajevo, on May 31, 1992 (AFP / Georges Gobet)

I remember radio journalists constantly on the air trying to wake the world up to the horrors of what was happening in Bosnia. But nothing improved on the ground.

Very quickly the ethnic origin of local journalists like me became a real danger. I could no longer pass “enemy checkpoints”. I was no longer a journalist doing my job. Instead I was reduced to an ethnicity by armed men twisted by hate.

We also had to deal with the propaganda from the Serb, Croat and Muslim sides. Needing sources beyond them to confirm information, I would spend entire days calling international sources in besieged areas or trying to talk to witnesses.

It was an important time for a lot of women journalists who were finally coming out of the shadows (like the two reporters featured in this Canadian documentary).

Covering war was no longer a man’s world, as had been with a few notable exceptions in earlier conflicts. And despite the competition, we worked together well and looked out for each other.

Civilians would grab you by the arm and pant, “Tell the world what is happening here.” But none of our innumerable articles or photographs changed the course of the wars in the former Yugoslavia, even though reporting them cost dozens of journalists their lives.

Three decades after the start of the Bosnian war, the memories of the women wracked by the loss of a child or relative imploring the Almighty to “open your eyes” still stay with me. I remember all the wedding photographs and snaps of happy family moments scattered in the gardens of abandoned homes and the unbearable stench of death.

Children in Srebrenica wave to UN peacekeepers, April 25,1993

(AFP / -)

Children in Srebrenica wave to UN peacekeepers, April 25,1993

(AFP / -)

The Dayton peace accord of December 1995 divided Bosnia into two entities, the Serb Republika Srpska and the Croat-Muslim Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Today the two are further apart than ever and distrust between their peoples is still enormous.

The war in Ukraine has revived these old traumas, so much so that in the first days after the invasion there was panic buying of flour in Sarajevo, with some people trying to get hold of iodine in case of a nuclear attack.

“The buildings there look so much like ours,” a veteran of the war told me, who can’t help himself from watching the rolling news on television for hours on end.

“It’s as if I am looking at the war from my kitchen window. I wake shouting after having nightmares. I’m afraid,” he said. In their minds, many Sarajevans have been plunged back into the siege.

In his sights: A view of Sarajevo from a position once held by a Serb sniper on the slopes of Mount Trebevic above the Bosnian capital on April 2, 2012 (AFP / Elvis Barukcic)

In his sights: A view of Sarajevo from a position once held by a Serb sniper on the slopes of Mount Trebevic above the Bosnian capital on April 2, 2012 (AFP / Elvis Barukcic)Sonia Bakaric is a journalist on AFP ’s French desk in Paris. Blog editors: Michaëla Cancela-Kieffer and Fiachra Gibbons in Paris