Turkey and Russia: still uneasy after all these years

Istanbul, December 3, 2015 -- At first glance, the black railings around the Transfiguration Cathedral in a quiet square in the Russian city of Saint Petersburg look like nothing extraordinary. But closer inspection reveals something else. The fence posts are not all standard metal bars but the largest are 19th century cannons, standing vertically and linked by chains.

These cannons were captured by the Russian imperial army from Ottoman Turkish forces in the Russo-Turkish War in 1828-1829 and later put to good use as trophies around the church and a symbol of Russian military might against Turkey. To this day, in the middle of this nordic city which spends half its year covered in a veil of snow, traces of the Ottoman calligraphic script can still be seen on the cannon.

A long and tangled history

It’s a stark reminder that the Ottoman and Russian Empires spent much of the last half millenium at war. The Russo-Turkish wars that started in the late sixteenth century and the Crimean War from 1853-1856 are etched into the modern public consciousness. Not to mention the so-called “Tatar-yoke” of mediaeval times when ancient Rus was ruled by Mongol-backed Turkic Tatars. The current flaring of tensions between Russia and Turkey following the shooting down of a Russian warplane on the Syrian border is, historically, no flash in the the pan but the latest dramatic confrontation between two powers who have constantly clashed for regional hegemony.

But for most of the over five years I spent as a correspondent in Moscow from 2008-2014 and in Istanbul since 2014, cooperation was the watchword in relations between Russia and Turkey. Disputes were set aside as officials rushed in and out to sign deals on trade and energy.

Two strongmen

The warming of ties was based on a strong personal relationship between the countries’ two strongmen, Vladimir Putin and Recep Tayyip Erdogan, leaders who have striking similarities. Now both in their early sixties, they are steering post-imperial societies into what supporters claim is a new dawn of stability and critics believe is a step back to the authoritarianism of the past. They have held both the posts of premier and head of state in order to cling on to power and make displays of political virility a key part of their image. Both also faced down unprecedented protests that challenged their rule -- Erdogan in 2013 and Putin in 2011-2012.

In one memorable episode in October 2009, Erdogan took part in a blokely conference call with Putin and his top buddy, ex Italian premier Silvio Berlusconi, where the three discussed football and energy pipelines. It seemed Erdogan, then premier, had become part of Putin’s macho boys club.

Italy's Silvio Berlusconi (L), Russia's Vladimir Putin (C) and Turkey's Recep Tayyip Erdogan (R) in northern Turkey, November, 2005. (AFP / Kerim Okten)

Italy's Silvio Berlusconi (L), Russia's Vladimir Putin (C) and Turkey's Recep Tayyip Erdogan (R) in northern Turkey, November, 2005. (AFP / Kerim Okten)The relationship reached its peak in December 2014 when Putin was invited to Erdogan’s glitzy new presidential palace as one of the very first visitors. We expected the ensuing press conference to produce the usual boilerplate official message of expanding bilateral ties while the more interesting behind-the-scenes dealing was kept secret. Instead, we scrambled as Putin emerged and stunningly announced that Russia was ditching a project for a major new energy pipeline with several EU companies and instead would work with Turkey on a new pipeline inevitably baptized Turk Stream.

What about the Syrian civil war where Ankara and Moscow have starkly different visions of the future of the country? Or Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, with its Tatar minority looking to Ankara for support in the face of their rough treatment by the new local authorities on the peninsula? The disputes, as analysts said, had been successfully “compartmentalised” as Ankara and Moscow focused on a new era of cooperation.

But when the unravelling came it was sudden and definitive.

A protester sets fire to a Putin poster during a demonstration against Russia in Istanbul, November, 2015. (AFP / Cagdas Erdogan)

A protester sets fire to a Putin poster during a demonstration against Russia in Istanbul, November, 2015. (AFP / Cagdas Erdogan)Ever since Russia began its air campaign in Syria in September, there had been fears of a mid-skies incident with a NATO member. But not even the greatest Cassandras among analysts and media seriously believed it would happen. At the end of October, there was excitement when Turkey announced it had shot down an aircraft that violated its airspace. But it turned out that the object was simply a drone (albeit Russian-made) that pictures showed was little bigger than a hobby enthusiast’s model aircraft. The story was rapidly forgotten.

The unthinkable happens

On the morning of November 24, it rapidly became clear that the worst had happened as the various elements of the story were confirmed one by one.

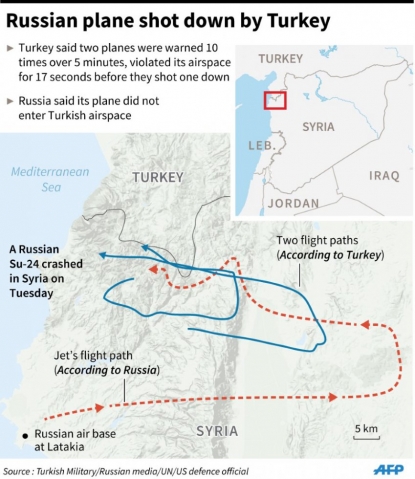

Aircraft shot down by Turkish forces. A manned war plane. Moscow confirms one of its planes. Turkey says there were 10 violations within a five minute period. Both pilots ejected, one killed (the circumstances remain unclear) and the other rescued. Russia, so often accused of being the aggressor, could paint itself as the victim and the Kremlin reaction was incandescent.

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)Almost 4.5 million Russians visited Turkey in 2014. For most of them, the Syrian war and niceties of Ankara-Moscow diplomatic relations were remote concerns. Charter flights would bring in thousands of Russians daily to the Turkish Mediterranean resorts, not just from Moscow and Saint Petersburg, but direct from cities in the Urals and Siberia to find some respite from the Russian weather.

They never dreamed of becoming bucket-and-spade weapons in a diplomatic conflict. But this was what they became when Russia’s foreign ministry swiftly warned its citizens not to travel to Turkey, prompting Russian tour agencies to stop selling tours and at a stroke denying the Turkish tourism industry its key market.

To hammer the final nail, Moscow announced it was lifting the visa-free regime for Turks whose announcement in 2010 and taking effect the following year had been seen as a direct product of the strong relationship between Erdogan and Putin.

Russian honour guards carry the coffin with the body of one of the pilots from the shot-down plane. (AFP / Russian defence ministry / Vadim Savitsky)

Russian honour guards carry the coffin with the body of one of the pilots from the shot-down plane. (AFP / Russian defence ministry / Vadim Savitsky)As the Kremlin machine geared into action, sanctions were agreed against Turkey while the future of key infrastructure projects, naturally including Turk Stream, were put at risk. The single incident above the Syrian border had within days affected swathes of people -- families from Siberia planning an autumn escape to Turkey, Turks in the south whose livelihoods depend on Russian tourism, Turkish business people with significant investments in Russia, Russians living in Turkey who suddenly began to feel deeply insecure. One Turkish man posted a viral picture on the Internet of him flying from Moscow to Antalya as the sole passenger on the plane. The effects of geopolitics on seemingly unconnected aspects of life can be ruthless and instantaneous.

Putin at Erdogan's new presidential palace outside Ankara, December, 2014. (AFP / Adem Altan)

Putin at Erdogan's new presidential palace outside Ankara, December, 2014. (AFP / Adem Altan)One of my favourite cities in Turkey is the northeastern city of Kars. Made quite famous through a novel by Turkey’s Nobel prize-winning novelist Orhan Pamuk, it’s a strangely alluring place. Partly because it reminds me of Russia. The streets are set out in an organised grid pattern. They are lined with beautiful mansions reminiscent of the best architecture of Moscow.

The Turkish city of Kars. April, 2009. (AFP / Mustafa Ozer)

The Turkish city of Kars. April, 2009. (AFP / Mustafa Ozer)This is because Kars was for four decades part of the Russian Empire, leaving an imprint that remains to this day and a permanent symbol of the struggle between Russia and Turkey for domination of the Black Sea and Caucasus region. The city was seized by Russia in the 1877-78 war but then fully won back by Turkey in the early 1920s in the wake of the Russian Revolution and Russia’s defeat in World War One.

Even in the years following World War II, Stalin’s regime made noises about the need for the return of Kars to the USSR, grumblings that only ended with the security guarantees Turkey received when it was fully aligned with the Western bloc in the Cold War and then became a NATO member in 1952.

For all the historical baggage, it would have seemed inconceivable to me over the last seven years that Turkey and Russia could have ended in such a dire position in 2015. There probably won’t be any (at least direct) war between Moscow and Ankara and no conflict that lasts 400 years. But there will be damage to a key geopolitical relationship which will be as severe as it is sudden.

Stuart Williams is AFP deputy bureau chief in Istanbul. Follow him on Twitter.

Putin and Erdogan in happier times, September, 2013. (AFP / Eric Feferberg)

Putin and Erdogan in happier times, September, 2013. (AFP / Eric Feferberg)