Stray bullets

Rio de Janeiro – “Stray Bullets.” The title was the one thing that really didn’t need any debate.

The goal was to tell the story contained in those two words -- the tragedy of innocent bystanders who fall victim to the deadly gun violence in Rio’s infamous favelas. They could be hit while playing in the schoolyard, sitting at home, going about their daily life minding their business. They can be of any age. A fetus was shot in its mother’s womb about a month after I arrived for my posting in Rio. I was shaken when I heard the news -- how can one be slain by a bullet before even being born?

The idea for the multimedia project came from Mauro, our local photo stringer, a “Carioca” (or Rio native) who knows the favelas inside and out. Why not do a story on the upsurge of violence in these “comunidades,” as the favelas are also called in Brazil, one year after the Olympic Games, with a focus on the people killed by stray bullets?

Bullet holes are seen on a wall of the house outside of which 13-year-old Henrique de Oliveira was shot dead during an anti-drug police operation in the Complexo do Alemao favela or shantytown in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on April 25, 2017. (AFP / Fabio Teixeira)

Bullet holes are seen on a wall of the house outside of which 13-year-old Henrique de Oliveira was shot dead during an anti-drug police operation in the Complexo do Alemao favela or shantytown in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on April 25, 2017. (AFP / Fabio Teixeira)In July the shootouts in the favelas had become so common that one newspaper started running reports under the tag line “war in Rio” and the army was called in to help quell the violence. Poorly paid police were not coping and in one area were accused of renting out weapons to gangs. Rio de Janeiro, the tropical postcard city, the city of samba, of beaches and of football, was in the midst of a cycle of violence and corruption that seemed to be spiraling out of control.

An app called “Fogo cruzado,” or Crossfire, tracks the mayhem in real time -- the places where there is gunfire, as well as the number dead, wounded and any police operations underway, so that residents can stay away from the affected area. Most cities have traffic apps; Rio has a shootout app.

We decided to do a multimedia project involving video, photo and text that would give a voice to the innocent victims of the violence, the residents who had nothing to do with the gangs controlling these poor neighborhoods of pastel-colored homes perched on hillsides overlooking the city.

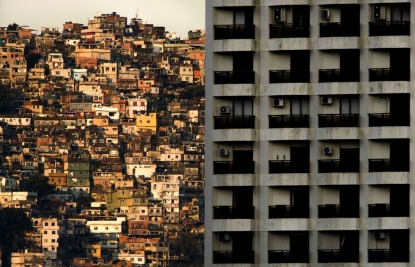

View of Rocinha (L) favela, in the background of a building of Sao Conrado neighborhood, the closest and one of the richest areas of Rio de Janeiro on Septemper 27, 2017.

(AFP / Mauro Pimentel)

View of Rocinha (L) favela, in the background of a building of Sao Conrado neighborhood, the closest and one of the richest areas of Rio de Janeiro on Septemper 27, 2017.

(AFP / Mauro Pimentel)Once we settled on the idea, we debated the approach -- how many people do we interview? In what format? Do we also interview policemen, sociologists, politicians? And how do we distinguish between the many different types of shooting victims, which also include traffickers and police?

We eventually decided that we would only interview people, mostly favela residents, who had either been shot themselves or had a loved one who’d been hit by a stray bullet. People told us how their lives were upended because they were in the wrong place at the wrong time, like Luciana Novaes, who was hit below her neck by a stray when she was in the canteen of her university.

The wound paralyzed almost her entire body and it took her a year before she could even speak again. Yet she has rebuilt her life, becoming a city councillor and says her greatest achievement is to have avoided sinking into bitterness. “I thank God every day that I am not angry,” she says.

Employing urban combat tactics, Brazilian army military police personnel patrol along an alley in the Rocinha favela in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil on September 25, 2017.

(AFP / Mauro Pimentel)

Employing urban combat tactics, Brazilian army military police personnel patrol along an alley in the Rocinha favela in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil on September 25, 2017.

(AFP / Mauro Pimentel)From the very first interview, the words were so powerful that we decided to film them against a black background, so as not to take away anything from the testimonies.

So we didn’t film the streets of the favelas themselves. But we did film personal belonging of the victims – children’s notebooks, shoes, sports medals -- objects that spoke of the lives cut short.

We eventually decided to interview only eight people to, again, amplify the power of the words.

Family and friends cry beside the coffin of 13-year-old Paulo Henrique de Oliveira, who was killed by a stray bullet during a police operation against drug dealers in the Complexo do Alemao favela or shantytown in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on April 26, 2017. (AFP / Yasuyoshi Chiba)

Family and friends cry beside the coffin of 13-year-old Paulo Henrique de Oliveira, who was killed by a stray bullet during a police operation against drug dealers in the Complexo do Alemao favela or shantytown in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on April 26, 2017. (AFP / Yasuyoshi Chiba)As we went along, we added layers to the project. AFP’s infographics service in Paris gave us the idea of including an interactive module, with graphics and maps to explain the context.

The project took more than four months of work by the bureau’s journalists in four languages -- Portuguese, Spanish, English and French.

We didn’t imagine the challenges our undertaking would pose. Everything from the technical aspects (which our colleagues at Paris infographics worked tirelessly to solve) to practical problems on the ground of just how to find our witnesses.

Although there are nearly two million Cariocas who live in the favelas, we could not go into some of the more notorious ones because of security concerns. So we had to work our contacts to find victims or their loved ones who would accept to talk to us. Sometimes it would take weeks of work to find a single one.

Local children stand behind a fence as Brazilian Armed Forces soldiers keep watch at the Morro dos Macacos favela (Monkey's hill shantytown) during a security operation in the area in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil on October 6, 2017.

(AFP / Mauro Pimentel)

Local children stand behind a fence as Brazilian Armed Forces soldiers keep watch at the Morro dos Macacos favela (Monkey's hill shantytown) during a security operation in the area in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil on October 6, 2017.

(AFP / Mauro Pimentel)Some people didn’t want to participate, like Claudinea, the young woman whose fetus was shot and who was overwhelmed by grief.

Often the people we were interviewing had to fight back tears. Sometimes we actually had to stop. We were all shaken by meeting those who almost never get a voice -- the men and women who are completely forgotten in this war. Some of the people whom we interviewed spoke for the first time about the tragedies that have turned their lives upside down. Some know that they will never see justice done for their pain and loss; others have lost an only child, still others an adored sister and often it has taken them a year or more just to find their footing again.

As journalists, we all live in the city, but we live in neighborhoods that are not nearly as violent as the favelas. But even we, from the comfort of our homes in the so-called “southern zone” of the city, hear the favela gunfire. But when we hear it, our lives are not in danger. We run little risk from stray bullets in our homes. We can go to the market in the morning without worrying if we will be able to return alive and well to our homes.

A Brazilian army soldier walks past a child, during a security operation at Barbante favela, where earlier in the week alleged drug traffickers destroyed a police post in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil on November 30, 2017. (AFP / Leo Correa)

A Brazilian army soldier walks past a child, during a security operation at Barbante favela, where earlier in the week alleged drug traffickers destroyed a police post in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil on November 30, 2017. (AFP / Leo Correa)This project has been extremely important for the journalists involved because, as many have said to me, “the victims of stray bullets are no longer just numbers, with each new victim we think of the ones we have met.”

After all the work, it was difficult to cut hour-long interviews to 90 seconds of soundbites and a few lines of text, but that was part of the challenge in coming up with an interactive mini-documentary that could spotlight these individual cases while keeping an eye on the broader issue.

We hope that we have managed to show the grief, helplessness, the sense of injustice, but also the courage and immense dignity of these human beings faced with irreparable loss. We are honored that they have confided in us.

In the Rocinha favela, September, 2017.

(AFP / Mauro Pimentel)

In the Rocinha favela, September, 2017.

(AFP / Mauro Pimentel)