Proud of Zimbabwe at last

Harare -- When Zimbabwe won its independence from Britain in 1980, I was just 14 and going to school in a small town west of Harare. I don’t remember the euphoria that swept the country and didn’t know who revolutionary leader Robert Mugabe was. But I'll never forget the days that he was removed from power 37 years later.

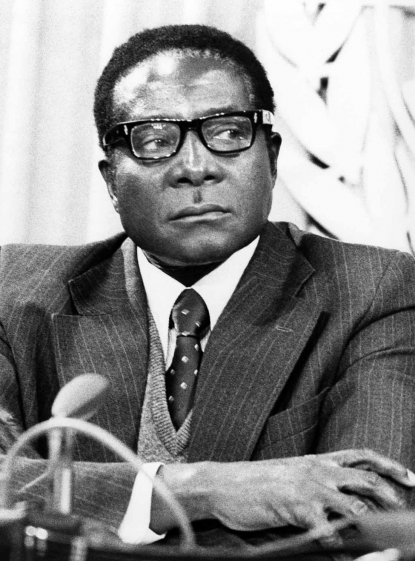

Robert Mugabe at the United Nations in March, 1978. (AFP / UPI photo)

Robert Mugabe at the United Nations in March, 1978. (AFP / UPI photo) Robert Mugabe in Harare in December, 2016.

(AFP / Jekesai Njikizana)

Robert Mugabe in Harare in December, 2016.

(AFP / Jekesai Njikizana)

As I grew up, I gradually learned more about the man who led the fight for independence. At first, he was the epitome of a liberator. A hero. An eloquent speaker. Arguably the most educated African leader at the time, with several degrees under his belt. He was praised worldwide as a statesman and his country Zimbabwe, a model democracy and the most literate African nation.

Robert Mugabe, then prime minister, gestures at a Harare stadium during a meeting on July 1, 1984.

(AFP / Alexander Joe)

Robert Mugabe, then prime minister, gestures at a Harare stadium during a meeting on July 1, 1984.

(AFP / Alexander Joe)

But with time, that image slowly changed. First came the seizure of white-owned commercial farms in 2000, which caused havoc in the all-important agriculture sector. Then came the hyperinflation and economic downturn -- the plummeting local currency, the empty supermarket shelves. And the steady crushing of political dissent.

Eventually the revolutionary who fought for freedom became a despot. Ordinary Zimbabweans did not dare criticise Mugabe in public. Neither did his ministers, whom he could hire and fire at will. Mugabe was feared. In the last twenty years of so, only the bravest Zimbabweans dared take to the streets to protest his rule. When they did, they bore the brunt of police brutality. As a journalist, I wrote quite a few stories of people hauled before the courts charged with insulting the president.

US journalist Martha O'Donovan (C), who was arrested on charges of insulting Zimbabwe's president and attempting to subvert the country's regime, talks with Zimbabwe Correctional Services officers as she leaves Chikurubi Maximum Prison near Harare, after being released on 1000 USD bail on November 10, 2017. O'Donovan was arrested after allegedly tweeting that the 93-year-old Mugabe was selfish and sick.

(AFP / Jekesai Njikizana)

US journalist Martha O'Donovan (C), who was arrested on charges of insulting Zimbabwe's president and attempting to subvert the country's regime, talks with Zimbabwe Correctional Services officers as she leaves Chikurubi Maximum Prison near Harare, after being released on 1000 USD bail on November 10, 2017. O'Donovan was arrested after allegedly tweeting that the 93-year-old Mugabe was selfish and sick.

(AFP / Jekesai Njikizana)Mugabe had become a fixture of Zimbabwe. To give you an idea of how much -- my niece was born a month after Mugabe came to power in 1980. Two hours before his resignation letter was handed to parliament, that same niece gave birth to her third child. Two generations born under his watch.

Like many Zimbabweans, I had resigned to the fact that Mugabe would die in power, that he would become a de facto president for life.

School children hold an image of Zimbabwe's President Robert Mugabe during the country's 37th Independence Day celebrations at the National Sports Stadium in Harare April 18, 2017. (AFP / Jekesai Njikizana)

School children hold an image of Zimbabwe's President Robert Mugabe during the country's 37th Independence Day celebrations at the National Sports Stadium in Harare April 18, 2017. (AFP / Jekesai Njikizana)As a journalist, my worst fear was how we would report the news of his death. I thought that he would die in Singapore, where he frequently received medical attention for years. I kept playing out various scenarios in my mind -- how will the news of his death be announced, how long after he actually died.

There was also uncertainty over the succession -- although the constitution allowed for one of the two vice presidents to take over for an interim period in the event of the president’s death, we weren’t sure who would come out on top, given the factional squabbling ravaging the ruling party.

Never in any of my scenarios did I imagine that Mugabe would resign under popular pressure after the military had taken control.

So when Zimbabweans poured out onto the streets last month, calling for the resignation of the only leader they have known since the end of colonial rule, it was surreal.

It felt like a dream -- a sweet dream -- to cover the protests without choking on teargas or fleeing water cannons, or police dogs, or baton-wielding riot police.

Zimbabwe opposition supporters clash with police during a protest march for electoral reforms on August 26, 2016 in Harare.

(AFP / Wilfred Kajese)

Zimbabwe opposition supporters clash with police during a protest march for electoral reforms on August 26, 2016 in Harare.

(AFP / Wilfred Kajese)I never imagined that I would live to see and hear a cabinet minister appointed by Mugabe stand up at a podium and declare to thousands of protesters that Mugabe must go, like Finance Minister Patrick Chinamasa did.

When I heard him say it, I thought there was something wrong with my hearing. I just simply could not believe what I was hearing -- the finance minister had just said that Mugabe Must Go!

It was a joy to see my compatriots -- from pre-teens to grannies -- finally enjoy the freedom to demonstrate, a freedom that is taken for granted in other countries, like South Africa. When a 14-year-old girl came up to me during the protests and said “Today feels like independence,” my heart ached -- this teenager was born in an independent Zimbabwe, but never knew what it felt like.

I myself had left Zimbabwe in 2006 and came back from time to time to cover large events like elections.

When Mugabe fired his deputy Emmerson Mnangagwa this fall, sparking off the protests, I returned. The firing was interpreted by many as paving the way for Mugabe’s wife Grace to assume power after him and seemed to be the straw that broke the camel’s back. Zimbabweans protested, piling pressure on the 93-year-old to finally step down.

Zimbabwe President's wife Grace Mugabe delivers a speech in Bulawayo in November, 2017.

(AFP / Zinyange Auntony)

Zimbabwe President's wife Grace Mugabe delivers a speech in Bulawayo in November, 2017.

(AFP / Zinyange Auntony)Mugabe announced his resignation as parliament debated an impeachment motion. The streets of the capital burst into a frenzy of partying.

My colleague who was in parliament at the time said his hands were shaking in disbelief as he sent through the direct quotes from the speaker of parliament who read out the resignation letter. If I had been in parliament, I would have also trembled.

It all happened so fast -- six days -- that I didn’t really have a chance to reflect on the momentous changes happening in my country.

It was only after his successor Mnangagwa was sworn in that it dawned on me that Mugabe, the only president that I had known, was gone.

A picture taken on December 14, 2017 shows a portrait of former Zimbabwe President Robert Mugabe after it was removed from the hall during the 107th annual conference of the Zanu-PF Central Committee at the party headquarters in Harare on December 14, 2017. (AFP / Jekesai Njikizana)

A picture taken on December 14, 2017 shows a portrait of former Zimbabwe President Robert Mugabe after it was removed from the hall during the 107th annual conference of the Zanu-PF Central Committee at the party headquarters in Harare on December 14, 2017. (AFP / Jekesai Njikizana)It was a moment of mixed emotions.

Yes, it was time for him to go. But there was also a tinge of sadness about the way he had to leave.

I asked myself -- why didn’t he step down 20 years ago? It would have given me much pride to refer to him in my stories as ‘the revered founding father of the nation’ or something like that – in similar fashion as I would write about the likes of South Africa's Nelson Mandela or Zambia's Kenneth Kaunda.

But he missed the opportunity to leave when he was still admired and liked – as his 93-year-old cousin told me a day after he resigned.

I must confess that it still feels bizarre to refer to him as the ex-president of Zimbabwe. Mugabe was Zimbabwe and Zimbabwe was Mugabe.

I’m still trying to get used to writing Zimbabwean President Emmerson Mnangagwa -– a slightly longer and not so easy to pronounce surname that I’m teaching my teenage son and my non-Zimbabwean colleagues to pronounce correctly.

After he stepped down I realised I didn’t have any Mugabe souvenirs. I then scavenged around friends' places just for a little piece of something with Mugabe’s portrait on it. It happened that his Zanu-PF party had started distributing fabric ahead of their December congress, which Mugabe was expected to lead. So I secured myself a two-metre piece of fabric with Mugabe’s portrait printed on it – a piece of history which might one day find its way into a museum.

And for the first time ever, I felt proud to be a Zimbabwean and my country’s flag is one of my new acquisitions.

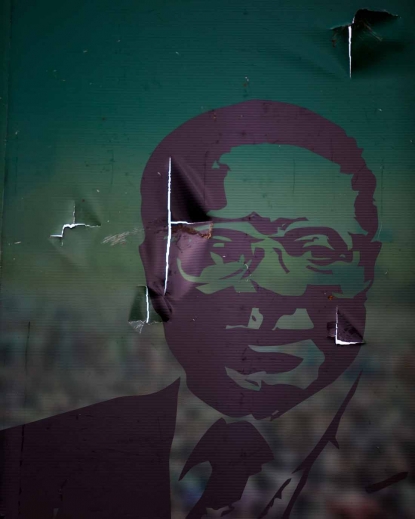

A vandalized billboard of Robert Mugabe stands in front of his party headquarters in Harare on November 19, 2017.

(AFP / Jekesai Njikizana)

A vandalized billboard of Robert Mugabe stands in front of his party headquarters in Harare on November 19, 2017.

(AFP / Jekesai Njikizana)