Slow travel to Saint Helena

JAMESTOWN, Saint Helena, June 9, 2015 – When Saint Helena appears on the horizon at dawn, after five days at sea, I can’t help but feel privileged. For years I have dreamed of travelling to this remotest of islands, all but cut off from the world out in the South Atlantic.

A few months from now, an airport will be opening on the British islet. But until then it remains one of the last places on Earth accessible only by boat. And the crossing from Cape Town, a case study in slow travel for our hyper-connected world, only adds to the sense of anticipation.

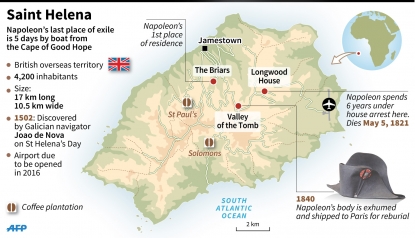

Saint Helena is forever linked to the name of Napoleon, who died there in 1821 after a six-year exile as prisoner of the British crown. My heart had been set on visiting ever since my grandfather, an amateur historian, took me to see the emperor’s grave at the Invalides hospital in Paris. But it was not until 2011, when I was named to AFP’s Johannesburg bureau, that my dream suddenly seemed within grasping distance.

A statue of Napoleon at the Consulate hotel in Jamestown, on the British island of Saint Helena (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)

A statue of Napoleon at the Consulate hotel in Jamestown, on the British island of Saint Helena (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)From Cape Town, I knew that a mysterious ship – the RMS Saint Helena – sailed once every three weeks carrying goods and passengers towards the tiny isle I used to pinpoint on a globe as a boy. I had four years ahead of me to fulfil my ambition.

Waiting for Mandela

There was one – sizeable – hurdle in my way: Nelson Mandela. From next year it will take just four hours to reach Saint Helena from Johannesburg. But for now, it implies a three-week round trip. First you must head to Cape Town – 1,400 kilometres and a two-hour flight away – and spend the night there before boarding a ship whose departure time can change at a moment’s notice. Five days at sea to reach the island, eight or nine on site, and then the return journey.

A maritime chart showing the island of Saint Helena, on the bridge of the RMS Saint Helena (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)

A maritime chart showing the island of Saint Helena, on the bridge of the RMS Saint Helena (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)For a correspondent in South Africa at that point, with the anti-apartheid hero’s health in sharp decline, it was unthinkable to be away for that long, without the possibility of getting back in an emergency. It saddens me to say it, but in a sense Mandela’s death in December 2013 frees me to make my trip before my South African posting comes to an end.

A rock where nothing ever happens

I book my ticket a year in advance. Since this is anything but a tourist destination, there are no travel guides on the market. By chance, I find a rare, lone copy of a 2007 Bradt guide to Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha (two other British rocks in the South Atlantic), offered online by a library in Seattle. Things are starting to take shape.

The RMS Saint Helena leaves Cape Town for Saint Helena, on March 5, 2015 (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)

The RMS Saint Helena leaves Cape Town for Saint Helena, on March 5, 2015 (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)As a journalist, I can’t imagine travelling to such an improbable place as a mere tourist – without bringing back the slightest story or picture for AFP. Of course there is no question of AFP funding such an extravagant assignment – a 5,000 euro trip all told – to a bare rock where nothing ever happens.

But 2015 is the bicentenary of the Battle of Waterloo and the start of Napoleon’s exile. The story is timely, and we end up finding an agreement – on the eve of my departure – for AFP to share my travel expenses and pay me for five days of work on the island. The rest is my own holiday time.

It’s a win-win situation – the agency gets a series of original stories from a far-flung dateline. I get to part-finance my dream trip, while travelling to Saint Helena as a journalist gives me the legitimacy to knock on far more doors, and meet more people than I ever would as a simple tourist.

Relaxing on board the RMS Saint Helena (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)

Relaxing on board the RMS Saint Helena (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)It is quite something in our day and age to leave point A on a Thursday, knowing you won’t reach point B until the following Tuesday. But I find myself adapting quite happily to the rhythm of a five-day cruise on board the RMS Saint Helena. I read up on Napoleon. I get to know my fellow passengers, sharing gin and tonics as we watch the sun set on the ocean. I even find myself joining in the games out on deck: from bingo and skittles to a ‘Frog racing’ game involving string-pulled little wooden frogs.

Bingo and 'Frog racing'

There are islanders heading home from the continent, South Africans employed to build the new airport, a young Frenchman come to do maintenance work on a surveillance station set up under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. There is an aristocratic Englishman who fought in the Falklands war, and a bearded Afrikaner tracking down his great-great-grandfather – General Piet Cronje –imprisoned by the British on Saint Helena during the Second Boer war in 1900.

Captain's cocktail time on the RMS Saint Helena (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)

Captain's cocktail time on the RMS Saint Helena (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)Life on the Royal Mail Ship is exotic in itself, with its old-fashioned rituals, the Saint Helena notes and coins in circulation on board, the fact the clocks change every two days and that the ship’s exact position is announced every day at 12.30 pm sharp.

Deliciously dated

Formal dress for men is theoretically de rigueur at supper, where we are placed according to a seating plan – and I find myself thrown in with fellow French passengers. I am aware that we are among the last people to experience this deliciously dated form of travel. The RMS Saint Helena will stop making regular crossing as of April 2016 when flights to Johannesburg begin.

The RMS Saint Helena anchored off Jamestown (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)

The RMS Saint Helena anchored off Jamestown (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)For a journalist, it is strange and intriguing to be so cut off from the world, although you can – at a push – pick up BBC radio in your cabin, or if in dire need connect via a satellite telephone or a slow, exorbitantly-priced WiFi link.

Telecommunications on the island itself are scarcely better: phone and data calls are even costlier than at sea, and the first mobile network is not expected until the end of this year.

The Jaguar belonging to the British governor of Saint Helena outside the seat of local government in Jamestown (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)

The Jaguar belonging to the British governor of Saint Helena outside the seat of local government in Jamestown (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)Tiny Saint Helena is a country in itself, with its own government, its 15-seat parliament, its own laws and judiciary, its currency and stamps. All for a population of 4,200 people, all of them descended from English colonists and African slaves - since the isle of eight by eighteen kilometres was uninhabited before settlers arrived in 1659.

Drivers greet one another in passing

Needless to say you’re soon picked out as a visitor. You keep running into the same people, over and over, who greet you each time. And soon you realise that everyone here spends a lot of time exchanging greetings. Even drivers crossing in the street. David Pryce, a British insect specialist, tells me drivers here end up with sore wrists, from performing constant gear changes with the left hand as they navigate the volcanic island’s narrow, winding roads, and constant greetings with the right.

The island’s chief settlement, Jamestown, is little more than a large village set in the bed of a steep valley, a handful of streets with colourful houses and slightly faded-looking shops. The 699 steep steps of Jacob's Ladder lead up to the site of a former fort, with splendid views out over the ocean.

If you spot something – buy it quick!

Beyond Jamestown, the island is charming – if scruffy in parts - with a tropical climate cooled by the ocean breeze. There is an undeniably tacky feel to the Saturday night seafront parade of youths with underglow lights on their cars, flashing red, purple and green outside the open-air discotheque.

Half-empty shelves in a store in Jamestown (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)

Half-empty shelves in a store in Jamestown (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)There is no supermarket as such and shopping for daily provisions turns out to be something of a lottery. Shop stalls are often bare. The local advice is to shop right after the boat comes – once every three weeks, before everything disappears. “You won’t starve, or course,” David Pryce tells me. “But you had better not set your heart on anything too specific.

“You need to do the round of the shops every day – and if you spot something, buy it quick!”

One of the world’s best coffees

The best restaurant in Jamestown is Thai. Its pubs offer local gin or beer from South Africa and Namibia. Saint Helena itself is no foodie destination, but it does boast one of the world’s best coffees – a variety imported from Yemen by the East India Company in 1732 and which has remained genetically pure thanks to the island’s isolation. It is also extremely expensive.

Jamestown, the capital of Saint Helena (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)

Jamestown, the capital of Saint Helena (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)Jamestown is home to what must be the only Napoleon Street in the United Kingdom. Both Longwood House where the emperor lived out his last days, and the vale where his body lay until it was repatriated to Paris in 1840, were sold to France by Queen Victoria in 1858.

A bucolic walk through “Geranium Valley” leads the visitor to Napoleon’s empty tomb, at a spot which he chose himself. In the Jamestown archives, the registry of deaths for May 9, 1821 reads: « Napoleon Buonaparte, late emperor of France, he died on the fifth instant at the old House at Longwood and was interred on Mr. Richard Torbett's estate.”

Napoleon Bonaparte's former tomb in Jamestown (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)

Napoleon Bonaparte's former tomb in Jamestown (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)As a journalist I get to meet the French curator who has watched over the site since 1987. Michel Dancoisne-Martineau is quite a character, and usually prefers to keep to himself. The 49-year-old is working to preserve the memory of Napoleon on the island thanks in part to a donation from the Napoleon Fund.

He for one is certain that the airport will mean a surge in tourist numbers – compared to the few dozen who have the inclination, time and money to make the long trip by sea.

A public swimming pool in Jamestown (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)

A public swimming pool in Jamestown (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)Napoleon aside, Saint Helena’s main tourist asset is its unspoiled nature – the walking paths along the craggy coastline, the boat tours and dolphin sightings. Provided, that is, the weather cooperates. For the weather here is notoriously fickle, as Napoleon bitterly complained.

The authorities here are betting on 30,000 visitors a year – against just 1,500 at present. Undoubtedly the new air link will attract Napoleon die-hards, and deep sea divers looking for a new spot to explore. But I can’t help wondering how many people will really come this far – catching a flight to Johannesburg, another to Saint-Helena – when the magic of slow travel is gone.

Jean Liou is an AFP correspondent in Johannesburg.

Tourists visit the site of Saint Helena's future airport in March 2015 (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)

Tourists visit the site of Saint Helena's future airport in March 2015 (AFP Photo / Jean Liou)