The sentry in the north

Lagos - When she was eight years old, the daughter of Aminu Abubakar, AFP’s correspondent in Kano, Nigeria’s second biggest city, asked him why he worked all the time. “I said it’s because in my work I always need to tell people around the world what’s happening here,” he said, in a composed voice.

“Here” for Aminu means the whole of northern Nigeria - a region of about 100 million people. Blighted by 12 years of fighting between the army and Boko Haram jihadists, it has millions of displaced people. It breaks all the records for poverty, humanitarian suffering and violence.

Police on patrol in the village of Unguwar Busa, in Kaduna state, after more than 130 people were killed in February 2019 (AFP / Cristina Aldehuela)

Police on patrol in the village of Unguwar Busa, in Kaduna state, after more than 130 people were killed in February 2019 (AFP / Cristina Aldehuela) A child from the Fulani pastoralist community in northern Kaduna state (AFP / Luis Tato)

A child from the Fulani pastoralist community in northern Kaduna state (AFP / Luis Tato)Those of us based in the AFP bureau are in the south, in the lively economic and cultural megacity of Lagos. Life here isn’t easy or relaxing; sometimes it is even dangerous. But for Lagosians “the North” remains as foreign as a far-away land. And for AFP, Aminu Abubakar, who has just turned 50, is its sentry.

“I sleep when I am sure that everywhere is quiet,” he told me one day.

In spite of all the admiration and respect we have for our Kano correspondent of 21 years, when our phones ring, we dread seeing Aminu’s name come up as caller. We know it generally means bad news and that we’re in for a long night.

I remember December 31, 2016 very well. It was my first New Year’s Eve on call for AFP in Nigeria. At 10 to midnight as I was getting ready to bring out the champagne and the first fireworks were lighting up the skies of Lagos, Aminu filed a story to me.

How do you respond to that kind of mail? By saying: Happy New Year? The sad truth is that unfortunately we are used to covering such grim news stories. Too used, in fact. To the point that we’re often writing them at the kitchen table while listening to Afrobeat music. But it’s also true that we don’t report on every killing when the number of victims is fewer than 10. If we did, we’d be doing nothing but that.

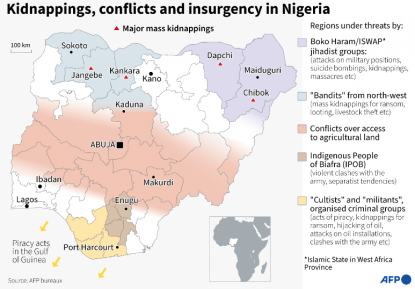

This country of 200 million people is plagued by several conflicts, jihadism, organised crime and piracy. But that’s not the full story by any means. Nigeria is also a hugely diverse, dynamic and open country, with the proudest, most curious people I’ve ever met.

Nigeria has creative, talented youth and a growing middle class (AFP / Emmanuel Arewa)

Nigeria has creative, talented youth and a growing middle class (AFP / Emmanuel Arewa)Its younger generation is creative and incredibly talented; its middle class is exploding and engaging. Nigeria cannot be reduced to just its atrocities - that wouldn’t be fair. At the same time, I hate telling Aminu: “No, we won’t cover that attack in Monguno or south Kaduna which claimed six lives.” I can feel an awkward silence at the end of the line.

I know what he’s thinking. Who will talk about these victims if AFP doesn’t? A life means just as much in Katsina as in Cotonou, or in Lyon. Except when they happen so frequently, the deaths cease to make headlines.

Editorially it’s a complicated balancing act, made all the more difficult by the fact that every day, Africa’s most populous nation is sinking further into extreme poverty, bringing with it unimaginable violence.

We thought we’d covered every kind of atrocity. Baby factories where women are locked up to procreate, child suicide bombers, large-scale massacres. But for three months now, the horror has reached a new level, as much of our daily reporting is about mass kidnappings of children for ransom. Criminal gangs are taking hundreds of innocent youngsters captive to get money.

The dormitory of the school in Kankara was left empty after gunmen abuducted its pupils (AFP / Kola Sulaimon)

The dormitory of the school in Kankara was left empty after gunmen abuducted its pupils (AFP / Kola Sulaimon)The first one - in early December in Kankara in northwestern Katsina state, where armed men kidnapped 344 boys - gave us all a real shock. Of course, there had already been the Chibok case in 2014, when 276 high-school girls were taken by Boko Haram. After that famous case, perhaps we shouldn’t have been so surprised.

However, when Aminu sent us the first video showing the ransom demand filmed by the kidnappers, we discovered that rather than being high-school students as we’d been saying, the victims were actually little boys. They must have been mostly between 11 and 13 years old and looked exhausted, with fear in their eyes and faces covered in dust and scratches.

A man whose son was among those kidnapped by gunmen at the Government Science Secondary school in Kankara, northwestern Katsina State, on December 16, 2020 (AFP / Kola Sulaimon)

A man whose son was among those kidnapped by gunmen at the Government Science Secondary school in Kankara, northwestern Katsina State, on December 16, 2020 (AFP / Kola Sulaimon)Our Abuja-based photographer Kola Sulaimon and video journalist John Okunyomih took an early plane to join Aminu in Kano, and then travelled on to Kankara. The team stayed nearly a week - the time it took to free the children - surrounded by worried or angry parents and several dozen youngsters who had managed to escape after the attack.

They interviewed a boy who had fled. He showed John, our video journalist, his feet. They were bleeding because the attackers had forced them to walk barefoot all night.

“I became emotional, because I have two girls, they are 13 and 10, and I was thinking it could have been them,” said John, who has been a video journalist for AFP for more than three years. “Emotionally it’s difficult. Apart from being a journalist, I am a human being, I am a father. And as a father today (in Nigeria), I’m afraid for my children.”

More than 300 young boys kidnapped by Boko Haram from their school in Kankara were returned after being freed in December 2020 (AFP / Kola Sulaimon)

More than 300 young boys kidnapped by Boko Haram from their school in Kankara were returned after being freed in December 2020 (AFP / Kola Sulaimon) The boys' parents were overjoyed at their return (AFP / Kola Sulaimon)

The boys' parents were overjoyed at their return (AFP / Kola Sulaimon)I wasn’t on the ground myself, but I clearly remember that interview. It left a lump in my throat. We are often sent interviews like that, by email or WhatsApp to add into our stories. We may not experience first-hand the parents’ sadness and feelings of helplessness, but we sense the violence of what they have suffered.

The worry for our colleagues on the spot is constant, not only for their physical safety but also the psychological impact of covering this kind of story.

More than 300 grls were abducted from the Government Girls Secondary School in Jangebe (AFP / Kola Sulaimon)

More than 300 grls were abducted from the Government Girls Secondary School in Jangebe (AFP / Kola Sulaimon)

One thing that particularly shocked me was what one distraught father said after 279 young teenagers were kidnapped in Zamfara state in late February. He said he would have preferred his two daughters to be dead, to knowing they were in the hands of “bandits”. We hesitated over whether to include the quote in our story. We wondered whether a reader in France, Germany or Japan could begin to understand such pain and read that without judging this father.

I wondered how Aminu, John and Kola had themselves reacted to this confession. As reporters, we have of course all been faced with difficult human situations at one time or another. But meeting a father, who describes his suffering at not knowing where his daughters are, if they are alive or what they are being subjected to, in this way - well, I’m not sure how I’d have been able to bear it.

A dormitory in the Government Science College in Kagara, where gunmen kidnapped dozens of students and staff on February 18, 2021 (AFP / Kola Sulaimon)

A dormitory in the Government Science College in Kagara, where gunmen kidnapped dozens of students and staff on February 18, 2021 (AFP / Kola Sulaimon)I asked them how they coped - and why they had immediately said they wanted to return to the field to cover the third mass kidnapping in less than two months - this time in Jangebe, in the northwestern state of Zamfara.

“The first one in Kankara was extremely difficult, I was overwhelmed by pain. It was hard to recover from it, I was disheartened,” said Kola, a talented 32-year-old.

The journey to Jangebe was hard and dangerous, Kola recalled. “But I’m on a mission for all the ones who are being kidnapped. Their spirits lift me,” he said. “I have in mind that it could be my brother, my sister, my friend and it helps keep me going, even if it’s a dangerous place.”

Parents wait outside the school where gunmen abducted students in Kankara in December 2020 (AFP / Kola Sulaimon)

Parents wait outside the school where gunmen abducted students in Kankara in December 2020 (AFP / Kola Sulaimon)When the AFP team reached the village, they found angry residents had blocked the road off to reporters. One journalist had even gone to hospital after being hit by stones. The atmosphere was very tense. “The community accused the local journalists and the local government of downplaying the kidnapping,” Aminu said.

The AFP journalists explained to the villagers that they worked for an international news agency and it was in the village’s interest to talk to us. “Their testimonies would put pressure on the government to act. The more they talked, the more the government would act.”

After a long discussion with the village leaders, our journalists were finally able to talk to a mother. It was difficult as she was crying a lot, Aminu recalled. “We didn’t want to push her too much, but actually she said that it was a relief to talk.”

Humaira Mustapha's two daughters were among hundreds kidnapped from school in Jangebe (AFP / Kola Sulaimon)

Humaira Mustapha's two daughters were among hundreds kidnapped from school in Jangebe (AFP / Kola Sulaimon)This photo, taken by Kola of a mother with her eyes shut but streaming with tears, was picked up around the world. Reporters from leading media organisations covered the kidnapping while NGOs and international figures, including Pope Francis, condemned the abductions, forcing the Zamfara state government to acknowledge the attack and act quickly.

As happened in Kankara, several days later the 279 high-school students were released after negotiations were held with the kidnappers, and a ransom presumably paid.

“It was a special moment,” said Aminu, who had practically not slept for four nights due to rumours of an imminent release. Although tired out, he felt “happy and fulfilled”, he said. “As journalists, we have an impact on people’s lives. We have a very important mission and responsibility.”

Some of the girls kidnapped in Zamfara State gathered upon their release on March 2, 2021 (AFP / Aminu Abubakar)

Some of the girls kidnapped in Zamfara State gathered upon their release on March 2, 2021 (AFP / Aminu Abubakar)Days later, another attack struck at a different high school. Then yet another, this time on a primary school. There were so many that we began to lose track. In the office we’d ask ourselves things like, was Kaduna in mid-March the fifth or sixth abduction of school children in recent months? Do we include the mid-December incident when 80 boys were kidnapped for one night? Should we just start writing “one of many”? Do we even alert it as breaking news if fewer than 50 children are taken?

In March in Kaduna state, 39 students were kidnapped. AFP reported it of course, but we did not send an alert - those news flashes in red that we send to our clients, that often roll along the bottom of TV news screens - and no reporters went to the scene.

Once again, it's an editorial fine line. If we cover every kidnapping, is there not a risk of encouraging others? Of serving their communication strategy of horror? How far are the criminals ready to go to shock global public opinion and demand more money?

Islamist group Boko Haram claimed this image showed one of its fighters with the kidnapped Chibok girls (AFP / Ho)

Islamist group Boko Haram claimed this image showed one of its fighters with the kidnapped Chibok girls (AFP / Ho)On March 22, relatives of the students taken in Kaduna demonstrated to complain about a lack of action by authorities. They blocked roads and carried placards, hoping to draw attention to their suffering.

“We beg you, God, to have pity on us and help save our children, to touch the heart of their kidnappers,” one mother implored, dressed in black, with both hands raised to the sky. At the time of writing it was April and the victims were still being held. One father died last month due to the stress of the abduction.

Aminu Abubakar meanwhile remains on guard. As I write, he’s busy investigating two massacres, one of 15 people, the other of eight, in the centre and north of the country. “We need to talk about what is going on because the media has the power to make people accountable for the situation,” he said.

But for this father of seven, it’s not a massacre or kidnapping that sticks in his mind most from his long career. It is the story of a 24-year-old man who built a helicopter in the grounds of his university out of old car and motorbike parts.

Moubarak Abdoullahi, 24, built a helicopter from old car and motorbike parts in Kano in 2007 (AFP / Pius Utomi Ekpei)

Moubarak Abdoullahi, 24, built a helicopter from old car and motorbike parts in Kano in 2007 (AFP / Pius Utomi Ekpei)Sophie Bouillon's book about Lagos during the Covid pandemic, Manuwa Street, is published in French by Premier Parallèle