Prepping for a perfect storm

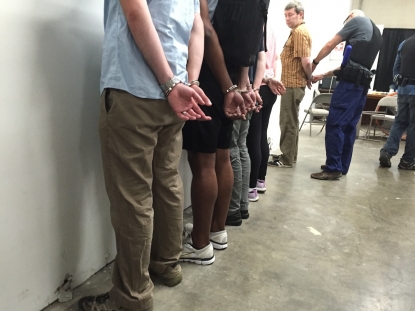

Washington DC -- There we were: seven journalists all lined up against the wall with our hands up, police officers screaming instructions behind us and occasionally hitting us with batons.

Even though I knew it was coming, I was still not prepared for this.

The officers yelling at us were actors and trainers. The batons were covered in foam. We were taking part in a simulation exercise during a two-day boot camp of sorts for journalists who report on civil unrest, and who are headed to the Republican and Democratic presidential nominating conventions this month.

Usually news organizations send journalists on conflict training courses when they are headed to war zones. But we were there for a different reason -- much of our course focuse on what might happen at the upcoming nominating conventions. Especially at the Republican convention in Cleveland where Donald Trump is due to be named as the official candidate from the party.

With reporters having had run-ins at Donald Trump events throughout this elections season, large protests expected against the brash candidate, and a police department that our trainers thought lacked experience in dealing with such large events -- our instructors thought the Republican convention had the potential of a perfect storm.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)Civil unrest training has become “a growth industry,” Frank Smyth, the founder of the firm that was training us, Global Journalist Security, told us.

Smyth has reported in dangerous places such as Iraq and Rwanda, and has specialized in journalist security at the Committee to Protect Journalists. He told us that the level of hostility toward the press in the US during this election cycle is the highest he’s ever seen.

Many news organizations have decided to supply their convention journalists with bulletproof vests and hard helmets. AFP is no exception. We will be taking those protections with us to Cleveland, and I will be reporting from the streets of the city with that gear at my disposal.

During the training, we were taught how to deal with hostile crowds, be aware of our surroundings and avoid becoming a target, defuse volatile interactions, deliver first aid, and deal with police.

That’s how we found ourselves up against the wall with our hands up -- being taught how to deal with police.

The yelling was so intense and jarring, I cannot even remember now exactly what was said.

We had been told that our most important goals were to be compliant and to stay calm (so that we could hear all of the verbal commands hurled at us).

But being told what to do and actually doing it are two different things.

Journalists participating in the training. (AFP / Nova Safo)

Journalists participating in the training. (AFP / Nova Safo)So there I was getting a whack from a foam baton on the back of my neck, because in all the yelling and confusion, I didn’t hear one particular order shouted at me.

It was only training, but as I kneeled facing a wall, my hands behind my back getting abused by a make-pretend officer, the feeling of dread and helplessness was very real.

“I froze up,” said one black journalist in the debrief following the simulation. (We agreed to maintain the privacy of all training participants, and not to name each other.)

When the instructors told us that one tactic that we can use during an arrest is to slowly reach for our press identification badges, this African-American man -- tall and in good shape -- retorted right away: “I ain’t reaching for shit.” He was concerned about appearing threatening to police.

"We do have to think of race. Religion and gender, as well,” an instructor told us during an earlier presentation. Such divisions were simply part of the realities on the ground, which journalists had to navigate to remain safe.

A protester is arrested during a demonstration outside the Hyatt Regency Hotel where republican presidential candidate Donald Trump was speaking in Burlingame, California on April 29, 2016. / AFP PHOTO / Josh Edelson (AFP / Josh Edelson)

A protester is arrested during a demonstration outside the Hyatt Regency Hotel where republican presidential candidate Donald Trump was speaking in Burlingame, California on April 29, 2016. / AFP PHOTO / Josh Edelson (AFP / Josh Edelson)We also got a harsh lesson in perceptions from a working police officer, who trains other officers in riot control. He was a guest lecturer. What he had to say was hard to hear, because it was completely contrary to how we journalists see ourselves.

Officers generally distrust the media, he said, and believe that we are quick to report and use information out of context -- wanting the story that “sells.”

At protests, he said police generally view the news media as an obstacle, believing that we incite protesters to get a bigger story -- either deliberately or by our mere presence.

At this point, there was palpable tension in the room.

In a question that seemed aimed at jabbing back at the officer, one reporter asked: Some protesters believe police are merely agents of government and are not to be trusted. How do you respond to that?

Officers do not see themselves that way, the officer said,most genuinely believe they are called to serve the public.

Then, he volleyed back at the journalists: How much does ego play into reporters getting caught up in hostile situations? Is it for bragging rights?

Ego can be a factor, came the response from a fellow reporter, but journalists also believe that they are serving the public.

At that moment, and perhaps only for a moment, a police officer and a group of journalists -- in a hot classroom inside a Washington-area warehouse -- found common purpose and common ground.

Police arrest a protestor during an anti-Trump demonstration outside the Anaheim Convention Center prior to a rally for Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump on May 25, 2016 in Anaheim, California. (AFP / Mark Ralston)

Police arrest a protestor during an anti-Trump demonstration outside the Anaheim Convention Center prior to a rally for Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump on May 25, 2016 in Anaheim, California. (AFP / Mark Ralston)I have been lucky in that I have never encountered the police as an obstacle during my reporting. Often, I have found them accommodating to the needs of reporters to get the story.

I can remember instances when officers took pity on me -- as I was getting lost in massive crowds or trying to figure out what was going on -- and allowed me to cross police lines to get to where I needed to go or find the commanding officer for more explanation.

In the days since the training course, we have experienced the aftermath of the Dallas shooting -- from officer funerals to frank discussions about race relations.

In response, Cleveland authorities announced a further tightening of security. They also have a long list of banned items from a zone around the convention, including knives, aerosol cans and tennis balls. Guns are allowed, because of Ohio state law.

As I prepared to head to Cleveland, I was still trying to reconcile the training I received with my fundamental beliefs of how to do my job and live my life. Should I be wary of those around me, of the police? Or should I continue to approach those I meet with the same sense of openness and curiosity that has fueled my journalism?

I don’t think I will know the answer to these questions until I am put to the test in real life. On the ground. In Cleveland.

Presumptive US Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump addreses a campaign rally at Grant Park Event Center in Westfield, Indiana. (AFP / Tasos Katopodis)

Presumptive US Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump addreses a campaign rally at Grant Park Event Center in Westfield, Indiana. (AFP / Tasos Katopodis)