The past we step into

Berlin - Sonja came into my life by happy coincidence, right in the middle of the pandemic. The message came, as so often in this hyperconnected year of physical isolation, in the form of a tweet.

The author of the message, Benjamin Preiss, was an Australian fellow journalist who had come across a blog post about my walk to work in Berlin. I had written it in January 2017, an unsettling time for me as an American after a deeply divisive election campaign had led to the inauguration of Donald Trump. Benjamin wrote:

Hey @doberah can you pls follow me so I can send you a DM? I read a piece you wrote mentioning my great aunt Lotte Iberman. Her younger sister (my grandmother) is living in Melbourne. I’d like to get in touch with you. Thanks.

— Benjamin Preiss (@bpreiss) July 26, 2020

Having lived in Germany since way back in Bill Clinton’s first term and Helmut Kohl’s waning years, I had long wanted to write a personal piece about Berlin’s landscape of historical memory that forces people to confront the ghosts of the past.

The jumping-off point for my essay was in front of my apartment building: two Stolpersteine, small personalised plaques remembering Holocaust victims. Called the world's largest decentralised monument, more than 75,000 Stolpersteine (stumbling stones) are now embedded in pavements throughout Europe.

(AFP Deborah Cole)

(AFP Deborah Cole)

Lotte (left), Sonja, and Ursula in sailor suits made by their mother (Photo courtesy of Sonja Cowan)

Lotte (left), Sonja, and Ursula in sailor suits made by their mother (Photo courtesy of Sonja Cowan)“Our Stolpersteine”, as my German husband and I call them because we make a point of taking care of them, honour Benjamin's great-grandmother and great aunt, Taube, also called Toni, and Lotte Ibermann. They lived on the ground floor of our building from 1939 until 1941, when they were rounded up in a nearby holding centre for Jews and then deported and murdered by the Nazis in the Łódź ghetto in occupied Poland.

Benjamin’s grandmother Sonja was Toni’s daughter and Lotte’s younger sister but had fled to the UK in 1939, before her family moved into our building.

Now years later, like a message in a bottle tossed in the sea, my piece had reached an unexpected destination on the other end of the earth. I responded immediately.

Benjamin and his family were living under a much more severe lockdown in Melbourne than we had yet faced in Germany. We said we looked forward to the day when transcontinental travel felt possible again and we could meet in person.

As a tribute to his German great aunt Lotte, he had named his young daughter Charlotte. And he said Sonja was thriving, even at 97, and eager to talk. I couldn’t believe my luck. I gave our Stolpersteine, which were laid in 2010, a fresh polish and sent a picture to Benjamin.

Sonja hosting a small 97th birthday celebration for herself in 2020 (Photo courtesy of Sonja Cowan)

Sonja hosting a small 97th birthday celebration for herself in 2020 (Photo courtesy of Sonja Cowan)Benjamin had already written movingly about Sonja’s rescue as part of the Kindertransport evacuation effort bringing children from Germany and Nazi-occupied Europe to the UK. But the family was hopeful that a stranger asking questions would bring other aspects of her remarkable life to light.

On a Sunday morning in Berlin in early September, I met Sonja via Zoom for the first time. She looked 20 years younger than her age in a pretty white and pastel top and a touch of rose lipstick.

Her daughter Lorraine who lives with her helped set up the computer and prompted her when she had trouble hearing. But once we started talking, the conversation flowed.

Sonja, her daughter Sandra, her grandson Benjamin and Deborah Cole on their first zoom call (AFP/ Deborah Cole)

Sonja, her daughter Sandra, her grandson Benjamin and Deborah Cole on their first zoom call (AFP/ Deborah Cole)

I wanted to know about her memories of our neighbourhood and how the loss of her family and homeland had shaped the rest of her life. To live in Berlin means to know that things do fall apart and the centre, against all hopes, often doesn’t hold. Democracies everywhere look troublingly fragile today. It all made me wonder how Sonja, one of a rapidly dwindling number of Holocaust survivors around the world, had experienced the Berlin life she knew crumbling, slowly at first, then all at once.

“I haven’t got much time left. So I live from day to day, especially now while I’m eingesperrt (locked up).” Sonja had a cracking Australian sense of humour combined with a dry matter of factness that pointed her out instantly as a born Berliner. She had come back to the city twice since the war, once with her husband when she turned 70, and again to celebrate her 90th birthday. It was a joy to see she was in good health, had led a rich life and was surrounded by family who loved her and shared an ardent interest in her story. She called them “mein Vermögen” (my fortune).

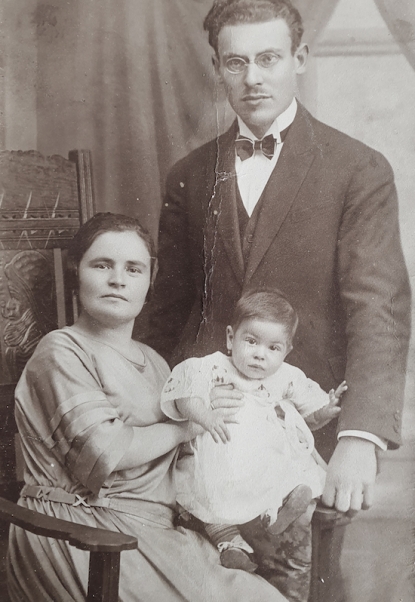

Sonja and her parents Toni and Leo (Photo courtesy of Sonja Cowan)

Sonja and her parents Toni and Leo (Photo courtesy of Sonja Cowan)Sonja was born in 1923, one of three daughters to an observant Jewish family in Berlin. Her parents came from Poland and spoke Yiddish and German with a strong Eastern European accent that marked them as immigrants. Her father died of a heart attack when she was just a toddler, leaving her pregnant mother Toni, to struggle as a seamstress to keep the family housed and fed.

“I didn't have a very good life as a child,” Sonja told me. She remembered long days accompanying her mother to an outdoor market near a canal in the Kreuzberg district where they sold skirts Toni had sewn. When there was time, Sonja played in the hilly green fields at the Hasenheide park and remembers planes from nearby Tempelhof airport whooshing overhead.

Lotte and Sonja (Photo courtesy of Sonja Cowan)

Lotte and Sonja (Photo courtesy of Sonja Cowan)After the Nazis’ rise to power when she was 10, Sonja was expelled from public school and forced to enrol at a Jewish institution. While she was still small, Lotte picked her up from school, once with a coconut in hand for them to share the milk through a straw. “She had lovely big eyes, a nice smile and she always wore earrings, from the time she was a baby,” Sonja said fondly. Toni sometimes didn’t return from work until late and the family often went to bed hungry. Hitler-supporting thugs were suddenly everywhere and had started harassing and intimidating Jews on the street. “When we saw the Nazis marching, we used to hide behind the big doors (of buildings). We didn’t want to say ‘Heil Hitler’,” she said.

By the time of the Kristallnacht pogrom in 1938 in which Jewish shops and synagogues were sacked and citizens terrorised, Sonja was already away at a Zionist training camp in rural Steckelsdorf west of Berlin, preparing for a move to Palestine. Seeing the writing on the wall, her mother Toni had a plan for the family’s survival. “My mum wanted us all to meet up in Israel.” Even as a city girl, she took to farm work. “I loved it. We were always climbing trees to pick the cherries.” Sonja told of a heart-stopping encounter on a country road with an SS officer who mistook her for a member of the Hitler Youth and offered her a lift. With a long trek ahead of her, she decided to hop on the back of his motorcycle.

In 1938 the Kindertransport programme had begun; the next May her younger sister Ursula, who had been living in an orphanage because Toni was too poor to keep her at home, would board a train for the UK.

Sonja, Lotte and Ursula soon before Ursula was sent to the UK on a Kindertransport in May 1939. The picture was taken at Berlin's Lustgarten park on Museum Island (Photo courtesy of Sonja Cowan)

Sonja, Lotte and Ursula soon before Ursula was sent to the UK on a Kindertransport in May 1939. The picture was taken at Berlin's Lustgarten park on Museum Island (Photo courtesy of Sonja Cowan)In August 1939, the staff at the Zionist camp called Sonja’s name for immediate transport to England. She swatted away any notion that such a move required bravery of a teenager. “I am a person who accepts anything and everything, I take everything in my stride.”

With another remarkable stroke of luck, she was 16, just under the maximum age for the journey that would save her life. For Lotte, the oldest sister, it was too late. Toni, a devout, earnest woman with the weight of the world on her shoulders, gave Sonja a brief handshake as she sent her off from the platform at Friedrichstraße station. It would be the last time they saw each other.

Sonja at about 16 years old (Photo courtesy of Sonja Cowan)

Sonja at about 16 years old (Photo courtesy of Sonja Cowan)

The next two years would see Sonja shuttle between refugee centres until she ended up at a farm school for Jewish children in Scotland. She and Ursula reunited there for about a year. Her journey there from northern Wales was tough. She spoke “not one word” of English and had to rely as a young woman on the kindness of strangers. “I wouldn’t do that today,” she told me with a wry smirk.

To escape a life of domestic servitude after her 18th birthday, Sonja decided to join the British army and served as a storewoman until the end of the war. She described those early days as some of the happiest of her life, finally giving her a sense of belonging and purpose after so many years adrift or on the run.

But it was also when the letters from her mother and Lotte stopped coming. The Nazis had sent them to the Łódź ghetto, the largest in Poland outside Warsaw. Sonja would learn only decades later with help from Berlin’s Jewish Museum that that is where they were killed.

Transparent photos featuring Jewish citizens of Lodz, before the war, inside the Lodz ghetto's museum, on August 29, 2004 (AFP / Janek Skarzynski)

Transparent photos featuring Jewish citizens of Lodz, before the war, inside the Lodz ghetto's museum, on August 29, 2004 (AFP / Janek Skarzynski)

After the war, Sonja returned to Glasgow to live with a Jewish family. They called her the “little refugee girl”. One day a young man named Ralph Cohen, who had also served in the army, came by to introduce himself. Decades on, she still savoured the romance of their first meeting. After she answered the door in her dressing gown and told him she had been about to wash her hair, he said: “I’ll do it for you, I’m a hairdresser.” A new love was born, one that grounded and sustained her after so much fear and sorrow, and they were married within the year.

Like her own mother, Sonja would have three daughters. In the face of anti-Semitism, the family changed its name to Cowan. Ralph eventually tired of Glasgow’s gloomy weather and limited job opportunities and suggested a move to the other end of the globe: Australia.

Sonja, who had been uprooted so many times in her life, was happily married and also ready for another change of scene. Although they settled in a Melbourne community with many survivors of the Holocaust, it was rarely talked about at home. “I get upset when I see reports on television about concentration camps, that sort of thing,” she said. “It still hurts.”

Sonja and Ralph Cowan on their wedding day in Glasgow in 1946 (Photo courtesy of Sonja Cowan)

Sonja and Ralph Cowan on their wedding day in Glasgow in 1946 (Photo courtesy of Sonja Cowan)

Sonja’s sister Ursula married in London after the war. Many years later she emigrated to the United States, dying there when she was in her 70s.

Sonja and I would end up speaking three times as a scorching summer in Berlin gave way to a golden autumn, always with other members of the family joining in on Zoom.

Thanks to her breathtaking stamina, they were long, satisfying chats that covered a lot of ground. We shared a lot of laughs too. Sonja got the giggles when I pronounced “Stallschreiberstraße”, the tongue-twister name of the street where one of her schools had been. She told me about her frustrations under lockdown. Her rabbi made a few house calls to her at the end of the driveway during the high holidays but life had ground to an often tedious routine. “No dancing!” she joked.

When I told German remembrance researcher Aleida Assmann about Sonja, she noted that the inventor of the Stolpersteine, Gunter Demnig, had wanted to create a “social sculpture”. The concept is borrowed from artist Joseph Beuys, whose own work the Guardian recently compared to “one vast Holocaust memorial”. “Remembrance at your front door can bring about unexpected blossoms, jumping from the brass plaque into the digital world and around the globe… If that isn’t a remembrance miracle!” she said.

So-called Stolpersteine (stumbling blocks) showing names of Holocaust victims are pictured in front of the Reichstag building, seat of the German lower house of parliament (Bundestag), in Berlin on January 30, 2018 (AFP / Tobias Schwarz)

So-called Stolpersteine (stumbling blocks) showing names of Holocaust victims are pictured in front of the Reichstag building, seat of the German lower house of parliament (Bundestag), in Berlin on January 30, 2018 (AFP / Tobias Schwarz)Philosopher Susan Neiman, who grew up in the Deep South as the daughter of a Jewish civil rights activist, published an insightful book in 2019 called Learning From the Germans in which she argues that the practice of Holocaust remembrance could help Americans address the toxic legacy of slavery.

I asked US historian Jill Lepore on a visit to Berlin in October 2019 what a more honest memory culture in America might look like. “We don’t have a tradition in the United States of truth and reconciliation — of any real, formal public reckoning with the atrocity of slavery and conquest, with the atrocity of Jim Crow segregation,” she said. “Among the reasons that that reckoning has never come, I think, is that those things are not truly over” — still reverberating in police violence, discrimination and mass incarceration.

People light candles on November 8, 2018 at the site of a former synagogue in Schwerin as Germany marks the 80th anniversary of the Night of Broken Glass (Kristallnacht), when Nazi thugs torched synagogues, smashed Jewish-owned shops and rounded up Jewish men across Germany on November 9, 1938. (AFP / Bernd Wuestneck)

People light candles on November 8, 2018 at the site of a former synagogue in Schwerin as Germany marks the 80th anniversary of the Night of Broken Glass (Kristallnacht), when Nazi thugs torched synagogues, smashed Jewish-owned shops and rounded up Jewish men across Germany on November 9, 1938. (AFP / Bernd Wuestneck)Two weeks after the terrifying siege of the US Capitol on January 6 by Trump supporters, posing with a larger-than-life Confederate flag and one wearing an unspeakable “Camp Auschwitz” sweatshirt, Joe Biden and Kamala Harris were sworn into office.

My mind was on Sonja and the many other Holocaust survivors I have interviewed over the years when 22-year-old Amanda Gorman electrified the world at the inauguration with a poem steeped in remembrance culture.

One line in particular resonated with me: “For being American is more than the pride we inherit. It is the past we step into and how we repair it.” Stepping into the past, sometimes, happens through art like the Stolpersteine creating unforeseen connections, and via technology bringing strangers across the world with a story to share together.

Grounded by corona restrictions, I’ve walked those Berlin streets I wrote about in my blog four years ago countless times again. The places seem the same and yet transformed. The Stolpersteine I often rushed past, a wheelie suitcase in tow, now have faces and stories attached. My landlords are open to our idea of hanging some pictures of Toni and Lotte in our foyer. My techie husband Hilmar would also like to create a QR code so passers-by can watch some of the conversations with Sonja on their phones.

There is much about 2020 I’d like to forget but there are a few things I will hold onto. One is Sonja and Hilmar singing in harmony the song “Heidenröslein”, written by Goethe, the German Shakespeare, and set to a melody by Schubert. Here is the translation:

More than 80 years after she learned them, the words were still on the tip of Sonja’s tongue, a tribute to Germany’s image of itself as the “land of poets and thinkers” -- a notion not unlike American exceptionalism. A dream it renounced slowly at first, then all at once.