Life in the time of coronavirus: Beijing

Beijing -- Every time I enter a building nowadays, I say a little silent prayer before a little plastic gun is pointed at my head. After all, the contraption literally holds the key to whether I get in or not.

Welcome to life in the time of the novel coronavirus in Beijing, the capital of the country worst affected by the virus that has wreaked havoc all over the world since it first jumped from as yet unidentified animal to a human a few months back in the central city of Wuhan.

The little plastic gun is an electric thermometer and it has become ubiquitous in China and in the battle against the virus and the COVID-19 disease that it causes. A fever is one of the first symptoms and so the right temperature is essential in entering your office building, the supermarket, restaurant, public transport or your apartment building.

The magic number is 37 C -- if the thermometer registers your temperature as less than that, you can go in and avoid being quarantined.

The taking of temperature has become a daily ritual for everyone living in the Chinese capital.

“At least I can have four free temperature checks each day,” one of AFP’s office assistants, Danni Zhu, joked once. “Once in the metro, once when coming to the office, once at the daily health ministry presser and once when I come back to my building.”

This photo taken on February 27, 2020 shows a worker has his temperature checked at the Zhejiang Xuda Shoes Co. factory in Wenzhou. (AFP / Noel Celis)

This photo taken on February 27, 2020 shows a worker has his temperature checked at the Zhejiang Xuda Shoes Co. factory in Wenzhou. (AFP / Noel Celis)At the office building housing the AFP bureau in Beijing, the hunt for infectees does not end with the temperature taking. First I have to produce a brand new “entry and exit” card that building management made for this epidemic and that allows people to come and go from the 31-story structure. Then I walk in front of an infrared camera that stands ready to catch the fevers the thermometer may have missed.

A man wearing a face mask has his temperature measured in a mall in the financial district of Lujiazui in Shanghai on March 4, 2020. (AFP / Hector Retamal)

A man wearing a face mask has his temperature measured in a mall in the financial district of Lujiazui in Shanghai on March 4, 2020. (AFP / Hector Retamal)In the elevator, there is a box of tissues, so that you don’t have to press the buttons with your bare hands. And at our office, the keypad where I have to press the entry code is covered in plastic (easier to disinfect and replace).

(AFP/ Beiyi Seow)

(AFP/ Beiyi Seow)On this particular day my temperature was 35.2 (a bit low, but who cares? As long as it’s not near 37…), I walk in to an unpleasant surprise -- there is no more heat. Winter is far from over, but building management decided to cut off the central heating, fearing that the virus could spread through the pipes. To be fair to them, aside from AFP, there are very few offices that remain open, but still... Looks like we’ll have to layer up and think of alternative solutions. It’s a bit surreal to come into work in a freezing, nearly deserted building, where four radiators struggle to heat up our office.

A sign on our door reminds us that there can be no more than 12 people in the bureau at once (half of our staff normally) and security guards check in occasionally to make sure we’re complying. “You have to wear a mask, even when you’re working,” one of them says during one such inspection.

Coughing has become a social taboo -- every time someone does it, all heads in the office turn their worried glances toward the perpetrator.

Shanghai, le 3 mars 2020 (AFP / Hector Retamal)

Shanghai, le 3 mars 2020 (AFP / Hector Retamal) Beijing, January 28, 2020. (AFP / Nicolas Asfouri)

Beijing, January 28, 2020. (AFP / Nicolas Asfouri)

Outside, wearing a mask has become mandatory pretty much everywhere, even in the parks, since the city of Wuhan, where the virus originated, was put under quarantine at the end of January.

In the Ritan park, near our office, a long message plays over and over again on loudspeakers, reminding visitors to practice good hygiene. “Do it for Wuhan, for China, for humanity,” it intones.

Beijing park, March 5, 2020. (AFP / Str)

Beijing park, March 5, 2020. (AFP / Str)With faces covered by face masks, people no longer smile. And in the street, pressure to comply is very strong. One day I was eating a sandwich sitting on a bench when a passerby motioned for me to put my face mask on. I told him that it wasn’t very practical to wear a mask while attempting to eat one’s lunch.

In the first few weeks of the epidemic, the streets turned empty as people stayed home. The stores are still closed. In the evening, the few restaurants and bars that are open must limit customers to half their capacity and with no more than three people per table.

A lot of restaurants are only offering take-out or delivery services.

One of our editors, Eva Xiao, saw a Starbucks where all the chairs had been put away, to emphasize that customers weren’t allowed to linger after getting their lattes and mochas.

One evening, I was having dinner with a few colleagues in a French restaurant when three policemen appeared suddenly, screaming into their face masks that the restaurant was too full -- there were about 50 diners and staff inside instead of the allowed 21. No choice but to finish our dinner early. The last time I checked, the restaurant was still shut.

It’s not very easy to invite people to your home either -- a notice in my apartment building’s elevator cautions against guests and reminds one that people arriving in Beijing from the provinces or from a “risk” country must remain under quarantine for two weeks.

There isn’t too much to do during weekends -- museums, libraries, temples and gyms are closed, as are tourist attractions like the Forbidden City. The little streets that give the old part of Beijing so much charm have been cordoned off -- neighborhood volunteers stand guard in front of metal barriers erected at the entrance of these passageways, letting in only residents.

Beijing, February 22, 2020. (AFP / Nicolas Asfouri)

Beijing, February 22, 2020. (AFP / Nicolas Asfouri)In this sinister atmosphere one day I came across a woman who was dancing all alone between the Drum and Bell Towers in the heart of old Beijing. Normally you come across groups of women dancing in this neighborhood, now it’s just her, moving sadly to the sound from her transistor radio.

The official response to the virus took a while to get organized and was at first chaotic at times. Take the first presser organized by the health ministry three days after Wuhan and its 11 million residents was placed in quarantine. Before the start, journalists wearing face masks were ordered to take them off so as not to appear on camera with them.

But “when the presser started the de-masked journalists listened as an official emphasized the importance of building a ‘face mask culture’ to prevent the virus from spreading,” Matthew Knight, our video journalist, told me.

Four days later, “that government worker who earlier patrolled the room making sure no journalists would be seen on TV in face masks now wears a face mask herself.”

And then you couldn’t even go into the presser without a face mask and the chairs for the journalists were place one meter from each other.

The foreign ministry takes another approach -- its press conferences were held for two weeks by text messages via the WeChat application.

On January 24, China went into a hibernation of sorts. It was the first day of the Lunar New Year holiday, when most Chinese go back home in the largest human annual migration on Earth. But this year, the holiday was extended to prevent the spread of the disease. Initially the extension was due to last a week. But today, millions of migrant workers who had gone back to their villages for the holiday, still aren’t back in Beijing.

Fear has kept most Beijingers at home. One night when I went home from the office on my bike, I didn’t encounter a single pedestrian, cyclist or car. It was surreal -- lanterns celebrating the year of the Rat swung everywhere, but I was alone in this normally bustling metropolis of 21 million. It was like being in a horror film. I got shivers. It was even spookier because a cloud of pollution still hung over the city -- with traffic and activity so reduced I would have expected it to disappear along with the life that normally pulsates through these streets.

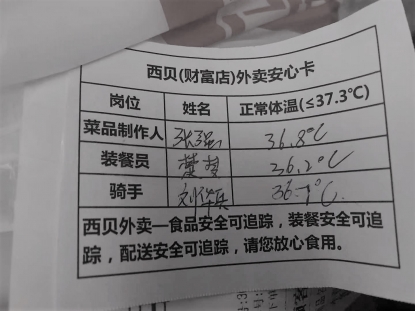

One of the problems that I worried about most was how to feed the bureau, with most shops and restaurants in our neighborhood closed. But then we ran into an unexpected piece of luck - a fast restaurant chain right in front of our office is still open. And the rare restaurants still open also offer delivery service. But even they will soon have to change their modus operandi -- they will now be prohibited from entering the buildings and will have to leave their deliveries outside. In addition to the price, the receipts for take-out food now also feature the temperature of the cook, the person who packed the food and the delivery man.

Know the temperature of who handled your food... (AFP / Eva Xiao)

Know the temperature of who handled your food... (AFP / Eva Xiao)Like the face masks, the electric thermometers took a while to become ubiquitous.

During one of the early days in the crisis, I arrived at work to find a uniformed security guard handing me an old fashioned mercury thermometer and orders me to put it under my armpit, all the while assuring me that it’s been disinfected.

“How long is this going to take?” I ask.

“Four to five minutes,” he answers. After two minutes I managed to convince him that my temperature won’t crawl past 36 since I’ve just come in from outside, where it was well below zero.

Having a low temperature can sometimes also pose a problem, as our chief photographer Greg Baker learned one day when the security guard refused to let him pass.

“He kept taking my temperature, but the electronic thermometer showed 24 degrees and at that temperature I should have been dead,” Grek joked recalling the incident. After checking with his direct superior, the guard finally let him in.

Editing by Yana Dlugy in Paris.

A man wearing a facemask as a preventative measure following a coronavirus outbreak which began in the Chinese city of Wuhan, sits at the Kai Tak cruise terminal where the World Dream cruise ship is docked, in Hong Kong on February 5, 2020. (AFP / Philip Fong)

A man wearing a facemask as a preventative measure following a coronavirus outbreak which began in the Chinese city of Wuhan, sits at the Kai Tak cruise terminal where the World Dream cruise ship is docked, in Hong Kong on February 5, 2020. (AFP / Philip Fong)