The traces they leave

Berlin -- Arriving in Berlin in the swinging mid-1990s, I found myself drawn not only to the young people reinventing the city, but also to their grandparents who were often generous with their recollections, sometimes dark and traumatic, sometimes rousingly inspiring.

Back then, there were still tens of thousands of people with vivid adult memories of World War II, the Holocaust and the beginnings of Germany's despised Cold War division. Sharing their stories often seemed to relieve a burden for them, and for me it fleshed out chapters of the past I had only read about in history books. I remember sitting in rapt silence while the elderly uncle of a roommate wept at our kitchen table as he recounted waiting out the terrifying Allied bombing raids as a boy in the cellar of his apartment building in 1945. A friend's mother recalled classmates in the 1950s who were the children of women raped by Red Army soldiers during the Battle of Berlin, some with distinct Central Asian features. Sitting on a patch of grass on a beautiful spring day, an ex-prisoner of Auschwitz and Buchenwald confessed to me that she feared her survivor's guilt had destroyed her own daughter's childhood.

An elderly woman lays a flower at Berlin's Platform 17 memorial during a cermony marking the 70th anniversary of the departure of the first convoys carrying Jews to concentration camps from the Berlin Gruenewald station, October 18, 2011. (AFP / John Macdougall)

An elderly woman lays a flower at Berlin's Platform 17 memorial during a cermony marking the 70th anniversary of the departure of the first convoys carrying Jews to concentration camps from the Berlin Gruenewald station, October 18, 2011. (AFP / John Macdougall)While I think seniors are generally invaluable as interview subjects, it counts doubly for Germany, which takes pride in its remembrance culture. The upheaval seen in this country in the last 70+ years means that the older the person, the more likely there is a rich seam of experiences -- of fear and persecution, of forgiveness and love -- they might tap and entrust with me. While the hardships my protagonists had to face were often uniquely German, their pain and pluck and joie de vivre sometimes seem strikingly universal. And because the number of those people with extraordinary stories dwindles each year, it has become for those of us based here, quite literally, a race against time to catch them before it's too late.

A 92-year-old man holds the hand of his carer in the Aliacare home for the elderly in Berlin, October 8, 2013.

(AFP / Odd Andersen)

A 92-year-old man holds the hand of his carer in the Aliacare home for the elderly in Berlin, October 8, 2013.

(AFP / Odd Andersen)When I heard about the remarkable Helga Weyhe, who at the biblical age of 95 still works six days a week as Germany's oldest bookseller, I knew she was gold. "I started in 1944 and I'm still here," Weyhe told me in her charming shop in ex-communist east Germany. Books got her through two dictatorships and would see her through her last chapter too. Beyond being a sharp-eyed witness to history, she was also a key reminder of a bit of advice middle aged people tend to start getting: never retire, at least not completely. Weyhe has certainly slowed down a bit in her twilight years (she takes a two-hour break for lunch and a nap). But anyone wondering why the Rolling Stones are still touring in their dotage need only see the passion that flickers in Helga's eyes when she gives spot-on book recommendations from behind the till.

Bookshop owner Helga Weyhe poses in her shop in the German town of Salzwedel on January 10, 2018.

(AFP / John Macdougall)

Bookshop owner Helga Weyhe poses in her shop in the German town of Salzwedel on January 10, 2018.

(AFP / John Macdougall) Bookshop owner Helga Weyhe poses in her shop the German town of Salzwedel on January 10, 2018.

(AFP / John Macdougall)

Bookshop owner Helga Weyhe poses in her shop the German town of Salzwedel on January 10, 2018.

(AFP / John Macdougall)

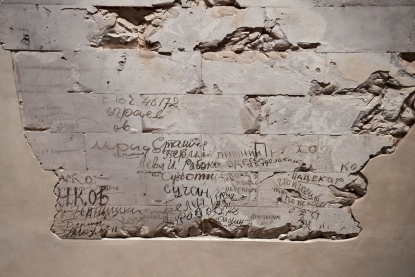

It was much the same with Karin Felix. Weeks before I met Weyhe, Felix walked me through a puzzling feature of the German seat of parliament, the Reichstag. Scrawled on its sandstone walls are graffiti left by Soviet soldiers during one of the last battles of World War II. It was a conscious decision to not plaster over these scars of history, Felix, a great-grandmother, told me. A former employee of the guest services department of the Reichstag, Felix has made it her life's work to record and annotate the messages. The long, bumpy road that took her to that calling and her iron-willed perseverance became nearly as interesting to me as those scrawled relics of the past.

Felix's estrangement from her family in the early days of communist East Germany, combined with a gift for languages, led her to throw herself into studying Russian at a specialised state trade school. But it was only after the Berlin Wall fell and the city again became the capital of reunited Germany that she was able to come into her own: building personal bridges of reconciliation with the old soldiers. I got the sense that the ageing former Soviet troops who begged her to show them the places they remembered from those terrifying last days of the war gave her a sense of purpose, as well as an authority and respect that she had long been denied under East Germany's oppressive regime. Whenever I start thinking about the limits of certain career paths, I remember Felix, in her seventh decade, becoming a respected expert in her field and working on her first book.

Graffiti left by Red Army soldiers at the end of World War II inside the Reichstag parliament building in Berlin, December 12, 2017.

(AFP / John Macdougall)

Graffiti left by Red Army soldiers at the end of World War II inside the Reichstag parliament building in Berlin, December 12, 2017.

(AFP / John Macdougall) Karin Felix, who served as a guide at the Reichstag parliament building for a quarter-century, poses in front the Reichstag builing in Berlin on November 23, 2017.

(AFP / John Macdougall)

Karin Felix, who served as a guide at the Reichstag parliament building for a quarter-century, poses in front the Reichstag builing in Berlin on November 23, 2017.

(AFP / John Macdougall)

There are so many stories of lives thwarted by Germany's heavy history, but there are also remarkable tales of triumph against the odds, like that of Hartmut Richter, who seemed to walk out of a Cold War thriller. Still armed with steely nerves in his late 60s, he told me about how he survived a daring escape across the Berlin Wall as a young man only to make repeated dashes back over the border to spirit more than 30 other people to freedom. Although he's told the tale hundreds of times, that brief shining chapter has filled him with enough pride to last a lifetime. Who knows when that opportunity could come for each of us?

Hartmut Richter poses for pictures along remains of the 'Wall' along Bernauer strasse in Berlin on October 8, 2014. (AFP / Odd Andersen)

Hartmut Richter poses for pictures along remains of the 'Wall' along Bernauer strasse in Berlin on October 8, 2014. (AFP / Odd Andersen) Hartmut Richter poses for pictures along remains of the 'Wall' along Bernauer strasse in Berlin on October 8, 2014. Richter fled the communist German Democratic Republic (GDR) in 1966 by swimming the Teltow canal and subsequently helped 33 other east German's flee before being caught trying to smuggle his sister and fiancee out. (AFP / Odd Andersen)

Hartmut Richter poses for pictures along remains of the 'Wall' along Bernauer strasse in Berlin on October 8, 2014. Richter fled the communist German Democratic Republic (GDR) in 1966 by swimming the Teltow canal and subsequently helped 33 other east German's flee before being caught trying to smuggle his sister and fiancee out. (AFP / Odd Andersen)

Bravery of a different but equally compelling sort came in the form of Fritz Schmehling, who fought for six decades to have his and thousands of other men's names cleared of convictions under a Nazi-era law against gays that remained on the books for decades after the war.

Schmehling, still nattily styled with brightly coloured braces and his grey whiskers twisted in a handlebar moustache, retained a wicked sense of humour and a zest for life that had seen him through decades of discrimination. And he's made lot of younger friends in the process as many of his old friends and comrades die. Schmehling, a cancer survivor, vividly recounted his youth of erotic adventure until he found his life's true love Bernd. His advice: create enough fantastic memories while you still can.

Friedrich Schmehling poses in his appartment during an AFP interview in Berlin's Steglitz district on November 7, 2016.

(AFP / Tobias Schwarz)

Friedrich Schmehling poses in his appartment during an AFP interview in Berlin's Steglitz district on November 7, 2016.

(AFP / Tobias Schwarz) Friedrich Schmehling poses in his appartment during an AFP interview in Berlin's Steglitz district on November 7, 2016.

(AFP / Tobias Schwarz)

Friedrich Schmehling poses in his appartment during an AFP interview in Berlin's Steglitz district on November 7, 2016.

(AFP / Tobias Schwarz)

Young love is easy to find but lasting partnerships can seem particularly precious for defying all the forces they're up against. Married couple and professional cinephiles Erika and Ulrich Gregor, who have watched at least a movie a day together for 60 years, are one such pair. There was something very German about their shared commitment to high culture as an edifying and uplifting force. And they were a sparky interview, full of tart remarks about contemporary trends and politics while never turning the snark on each other. The respect and affection the two had maintained across all those decades of marriage was obvious, and brought to mind the old Saint-Exupery quote that love is two people looking together in the same direction. In this case, a movie screen.

German married couple Erika and Ulrich Gregor pose in the lobby of a movie theatre in Berlin on February 8, 2018.

(AFP / John Macdougall)

German married couple Erika and Ulrich Gregor pose in the lobby of a movie theatre in Berlin on February 8, 2018.

(AFP / John Macdougall) German married couple Erika and Ulrich Gregor pose at a movie theatre in Berlin on February 8, 2018.

It's a love that was born in a cinema in 1950s Cold War Berlin and that's been nourished for over six decades by at least a movie a day together. It's that kind of shared passion that the Gregors say has kept their relationship thriving after nearly 60 years of marriage.

(AFP / John Macdougall)

German married couple Erika and Ulrich Gregor pose at a movie theatre in Berlin on February 8, 2018.

It's a love that was born in a cinema in 1950s Cold War Berlin and that's been nourished for over six decades by at least a movie a day together. It's that kind of shared passion that the Gregors say has kept their relationship thriving after nearly 60 years of marriage.

(AFP / John Macdougall)

The unique chapters of Germany's past have also found new and innovative purpose in places like retirement homes. In Dresden last year, I visited the Alexa senior living centre, where they have sought to recreate the lighter, apolitical sides of life in communist east Germany for seniors who grew up there. Called "memory rooms", the evocative decor and music were designed to help revive dementia patients' lost sense of self. The idea of losing our memory or health terrifies many of us and seeing the dignity and small pleasures the "clients" there eased my mind a bit about the dying of the light.

Residents sit together at a table inside an east German 60s lounge at a nursing home in Dresden, eastern Germany, on June 14, 2017.

(AFP / Tobias Schwarz)

Residents sit together at a table inside an east German 60s lounge at a nursing home in Dresden, eastern Germany, on June 14, 2017.

(AFP / Tobias Schwarz) Wheel chairs are parked inside an east German 60s styled lounge at a nursing home in Dresden, eastern Germany, on June 14, 2017.

(AFP / Tobias Schwarz)

Wheel chairs are parked inside an east German 60s styled lounge at a nursing home in Dresden, eastern Germany, on June 14, 2017.

(AFP / Tobias Schwarz)

Of course Germany's rapidly ageing population, high level of prosperity and world-class medical care mean that the pool of interesting seniors is simply huge: one in five Germans is over the age of 65. One of my favourite stories of reinvention was a Bavarian grandmother who, well into her seventh decade, decided pick up and move to the down-at-the-heel Berlin suburb of Hennigsdorf in the former east, where government subsidies abounded. There she launched what would become the world's biggest provider of contact lenses for animals. CEO Christine Kreiner had a crisp, no-nonsense air as she initiated me into the business of acrylic intraocular lens implants for lions, giraffes, tigers, rabbits, bears, rhinos and even owls -- all of which can go blind from cataracts. As a specialist in the visual, she was also remarkably elegant -- a reminder that at an age when the world often stops seeing women, self-respect and a bit of backbone can go a long way.

Then there are the ones who got away. Like many reporters, I take a wistful pleasure in writing obituaries, which allow me to spend time catching up on fascinating lives. In January I wrote about German Jewish swing musician and camp survivor Coco Schumann, whom I long wanted to get for an interview before his death at the age of 93.

(Getty Images/AFP / Johannes Simon)

(Getty Images/AFP / Johannes Simon)The melancholic feeling of sending off someone you very much wanted to meet gives you a strong sense of duty as a reporter -- you want to do right by them. I was also crushed to never meet Marion Countess Doenhoff. When her aristocratic family's ancient castle was set ablaze in 1945, Doenhoff fled west on horseback, arrived in the German media capital Hamburg and helped lay the foundations for independent post-war journalism. I devoured her memoirs soon after I wrote her obituary when she passed aged 92 in 2002.

But there were also the highly surreal experiences of meeting the history-makers themselves, the bold-faced names for the ages. Various assignments led me to speak to Hitler's favourite filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl (charismatic, elusive), the shadowy East German spymaster Markus Wolf (dashing, with a killer's eyes) and Nobel laureate Gunter Grass (a man with secrets) as well as statesmen like Helmut Kohl (frail but withering in the face of critical questions -- when I asked about making way for a successor, he stared me down with an ultra-formal 'gnaedige Frau' ("Madam")).

Journalism doesn't make many promises these days but I know that when I'm in my own twilight years, I'll have my own trove of stories to tell and memories to keep.

Berlin, June 18, 2008. (AFP / Barbara Sax)

Berlin, June 18, 2008. (AFP / Barbara Sax)