Vikings, teddy bears and rescues at sea

At sea in the Mediterranean -- Night had already fallen in the waters off Libya when the search and rescue mission began, breaking our two laid-back days aboard the Norwegian Siem Pilot, an oil supply ship converted into an EU patrol boat that has been plucking migrants from unseaworthy vessels in the Mediterranean.

AFP stringer cameraman Alessio Tricani and I had joined the crew in Catania for a week-long mission aboard the vessel of Frontex, the EU’s border management agency. Life on board was slow-paced at first (a journalist's nightmare but a personal treat!), and we spent the days getting to know the crew, a gentle, hospitable and largely-bearded bunch of Norwegian policemen and coast guards who serve a month at a time on board.

Then the call came through to head down to 20 nautical miles off Libya to transfer 900 migrants from an oil tanker which had picked them up from various dinghies and other vessels.

A member of Spanish humanitarian NGO Proactiva Open Arms, throws life jackets to refugees and migrants during a rescue operation off the coast of Libya on October 3, 2016.

(AFP / Aris Messinis)

A member of Spanish humanitarian NGO Proactiva Open Arms, throws life jackets to refugees and migrants during a rescue operation off the coast of Libya on October 3, 2016.

(AFP / Aris Messinis)It was pandemonium when we got to the tanker, with the migrants fighting over life jackets that they need to don for the transfer and each trying to get to the front of the line to be the first onto the Siem Pilot.

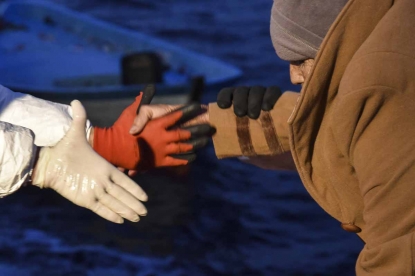

With Alessio manning the camera, I donned a protective suit and headed to the "red zone" on the Siem Pilot to hand out food, blankets and water to the arriving men, women and children.

To my disbelief, not only had pregnant women and mothers with toddlers made the crossing, but also a disabled man who walked on his hands and feet due to a deformed pelvis.

Members of Maltese NGO MOAS and the Italian Red Cross help an elderly woman to board the Topaz Responder ship during a rescue operation of migrants and refugees, off the Libyan coast in the Mediterranean Sea, on November 3, 2016. (AFP / Andreas Solaro)

Members of Maltese NGO MOAS and the Italian Red Cross help an elderly woman to board the Topaz Responder ship during a rescue operation of migrants and refugees, off the Libyan coast in the Mediterranean Sea, on November 3, 2016. (AFP / Andreas Solaro)Some of the migrants had been sitting in fuel while they were in their dinghies -- a particularly nasty but regular occurrence -- and had to be stripped, washed and have their burns dressed.

The medical team worked tirelessly through the night to treat or examine everything from open wounds to a woman with a brain tumour who insisted she had an appointment at an Italian hospital, though she did not know which one.

Undercover intelligence officers were also keeping an eye on migrants they thought could be possible smugglers or have information on the traffickers who had put them in boats from Libya.

The Siem Pilot crew had brought stuffed toys donated by their children and nieces and nephews to give to the children. I gave a grey elephant to a sad little Syrian boy, whose face lit up instantly.

Out at sea, a ghostly, now-empty white dinghy floated past in the dark. The ship's search light swept the area and suddenly fixed on the horizon: a fresh boatload of migrants.

Migrants and refugees wait for further assistance during a rescue operation by the Topaz Responder ship, run by the Maltese NGO Moas and the Italian Red Cross, on November 4, 2016 off the coast of Libya. (AFP / Andreas Solaro)

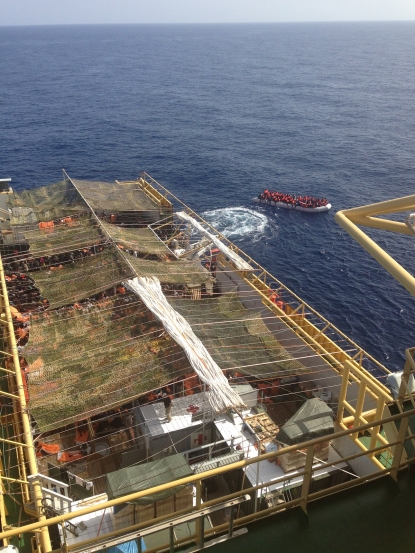

Migrants and refugees wait for further assistance during a rescue operation by the Topaz Responder ship, run by the Maltese NGO Moas and the Italian Red Cross, on November 4, 2016 off the coast of Libya. (AFP / Andreas Solaro)In all there were 12 new dinghies, which appeared in the darkness all around the Siem Pilot, the oil tanker and an Irish patrol boat giving a hand.

The transfer from the oil tanker was abandoned as the Siem's speed boats rushed to bring life jackets to those in the dinghies and take as many of them onboard as possible. Alessio, on one of the speed boats, had to abandon his camera as a four-day old baby was thrust into his arms.

A man holds a baby with a rescue blanket in his arms as a member of the Italian red cross examines them after they disembarked from the Topaz Responder, a rescue ship run by Maltese NGO MOAS, at the Brindisi's harbour on October 27, 2016.

(AFP / Andreas Solaro)

A man holds a baby with a rescue blanket in his arms as a member of the Italian red cross examines them after they disembarked from the Topaz Responder, a rescue ship run by Maltese NGO MOAS, at the Brindisi's harbour on October 27, 2016.

(AFP / Andreas Solaro)Watching the rescues, I was uneasy at first. The crew was very strict with the migrants, shouting at them to wait and even shoving some of them back as the desperate people, exhausted after several days at sea and terrified of drowning, scrambled to get off their dinghies. But my uneasiness eventually melted away once I saw how easy it was for those dinghies to flip over if too many people on them moved at once, and how people who didn’t get back when the speed boats approached could have their legs crushed. To keep the chaos and panic in check, the Norwegians had no choice but to be extremely strict.

Migrants and refugees panic as they fall in the water during a rescue operation of the Topaz Responder rescue ship run by Maltese NGO Moas and Italian Red Cross, off the Libyan coast in the Mediterranean Sea, on November 3, 2016. (AFP / Andreas Solaro)

Migrants and refugees panic as they fall in the water during a rescue operation of the Topaz Responder rescue ship run by Maltese NGO Moas and Italian Red Cross, off the Libyan coast in the Mediterranean Sea, on November 3, 2016. (AFP / Andreas Solaro) Migrants and refugees panic as they fall in the water during a rescue operation of the Topaz Responder rescue ship run by Maltese NGO Moas and Italian Red Cross, off the Libyan coast in the Mediterranean Sea, on November 3, 2016. (AFP / Andreas Solaro)

Migrants and refugees panic as they fall in the water during a rescue operation of the Topaz Responder rescue ship run by Maltese NGO Moas and Italian Red Cross, off the Libyan coast in the Mediterranean Sea, on November 3, 2016. (AFP / Andreas Solaro)

When working with the migrants, the rescuers wore special suits, goggles and sanitary masks. To humanize the first encounter, the crew had strapped a teddy bear to the back of the boat they used to get the migrants off their dinghies.

By midday, as the sun beat down, there were still four full dinghies around the Siem Pilot, but we were at full capacity -- 1,099 people -- and it would have been dangerous to take more people onboard.

People rescued on the Siem Pilot. (AFP / Ella Ide)

People rescued on the Siem Pilot. (AFP / Ella Ide)One of the dinghies started its engine and began motoring towards us, those on board waving their arms and crying for help. We stood helpless on deck as the commander shouted at them to stay back, but several threw themselves overboard and started to swim towards us.

More followed until there were 25 people in the water. Fearing the rest would take the plunge too, setting off a chain reaction, the Siem Pilot pulled away.

It was a wretched moment. Save them, but put them where? The only answer was the oil tanker. So after having spent hours transferring people off its oil-slicked deck, the Siem Pilot crew began pulling people from the water and off the dinghies and putting them on the tanker.

I went up to the top deck, under the radar mast and exhaust pipes, to try sending our video images by satellite to the London video desk. The heat was oppressive and off in the distance came the mournful sound of whistles being blown by migrants sitting in yet another dinghy, as it floated sadly away from us.

A migrant wrapped in a survival foil blanket stands aboard the Topaz Responder ship, run by Maltese NGO Moas and the Italian Red Cross, while sailing to the port of Vibo Valentia, southern Italy, on November 6, 2016, after rescue missions off the Libyan coast. (AFP / Andreas Solaro)

A migrant wrapped in a survival foil blanket stands aboard the Topaz Responder ship, run by Maltese NGO Moas and the Italian Red Cross, while sailing to the port of Vibo Valentia, southern Italy, on November 6, 2016, after rescue missions off the Libyan coast. (AFP / Andreas Solaro)Covering earthquakes, coach crashes and shipwrecks for work teaches you to distance yourself from those suffering, so I was furious when I failed to fight back tears. But then the commander in charge of the operation shed one too, as he said how proud his was of his crew. After 24 hours of non-stop work, every migrant spotted alive by the Norwegian crew had been saved.

But we were not quite finished. The crew had to switch from rescuing people to collecting the bodies of those who had not survived the journey and had been found drowned or dead in their dinghies. It was humbling watching people who had been up all night saving lives expend their last bit of energy to transfer heavy bodies.

Speaking to the migrants was heartbreaking, as they had no idea of the difficulties that awaited them in Italy. One lovely 20-year old from Ghana said he was a trained carpenter but would do any work going, and when I told him there weren’t many jobs in Italy, he looked at me in all seriousness and said "You tell me which country to go to, and I will go". The only thing I could think of doing was warning him not to try the deadly crossing at Calais, and wish him luck.

I was torn between feeling hugely guilty about the nice cabin, shower and hot food waiting for me, and feeling glad that I was there to record what was happening and also to help the Norwegian crew with the migrants, many of whom spoke French. (The Norwegians spoke excellent English, but none of them spoke French). I could also help with problems that were certainly not urgent in the middle of the rescue operation, but that I still hoped made a little difference, like discreetly handing out sanitary towels to those in need or getting fresh nappies for a woman with a wailing infant.

On the Siem Pilot. (AFP / Ella Ide)

On the Siem Pilot. (AFP / Ella Ide)We set off for Palermo, but there was still a surprise to come: the 1,100th passenger arrived in the night, after a six-month pregnant woman gave birth to a little boy.

The Siem Pilot pulled into Sicily two days later, to cries of joy, songs and dancing on deck. The little Syrian boy to whom I gave the stuffed grey elephant clutched it tightly as he disembarked for an uncertain future in a new land.

Migrants and refugees wrapped in survival foil blankets rest aboard the Topaz Responder ship run by Maltese NGO Moas and the Italian Red Cross after a rescue operation, early morning on November 5, 2016 off the coast of Libya. (AFP / Andreas Solaro)

Migrants and refugees wrapped in survival foil blankets rest aboard the Topaz Responder ship run by Maltese NGO Moas and the Italian Red Cross after a rescue operation, early morning on November 5, 2016 off the coast of Libya. (AFP / Andreas Solaro)