Interview with an assassin

Medellin, Colombia, December 11, 2015 -- When I first mentioned to my kids that I was going to Medellin to interview Popeye, they were a bit taken aback. Popeye? The spinach Popeye? In Colombia?

My children have only been in Bogota for three months and are too young to know the blood-soaked “narcoterrorism” era that wreaked the country n the 1980s and 1990s, when drug lords fought the government and each other with ruthlessness and force.

I explain to them that Popeye is a nickname for Jhon Jairo Velasquez, the hitman for drug kingpin Pablo Escobar who has admitted to killing “250 people, maybe more” and plotting or ordering another 3,000 murders.

When they hear this, my kids stop laughing. My adopted daughter, who grew up in a notoriously violent township of Johannesburg exclaims “You’re not going alone I hope?”

“Of course not,” I tell her, saying that I’ll be accompanied by our photographer Raul Arboleda as we seek to interview Popeye at the grave of Escobar, his friend and patron.

Escobar's body lies on the roof of a house, moments after he was gunned down by police as he tried to escape authorities. December 1993. (AFP / Medellin police)

Escobar's body lies on the roof of a house, moments after he was gunned down by police as he tried to escape authorities. December 1993. (AFP / Medellin police)The cemetery of Itagui couldn’t be more appropriate for such an interview. It lies in the hills surrounding Medellin, overlooking the city that was soaked in blood and violence at the end of the last century.

When I get there the day before, I’m a bit nervous, not sure whether the interview will take place at all. Raul shares my anxiety -- Popeye had already delayed the interview several times, including the day before, and we’re not at all certain that he’ll end up talking to us.

Just to be on the safe side, we arrive way ahead of time on the morning of December 2, the 22nd anniversary of the death of Pablo Escobar, who was killed by police in 1993.

Raul had already seen “Pope” in a mall to schedule the interview and says he is a wary man who always arrives ahead of his interviewers, scans the surroundings and never sits with his back to a potential enemy. When he met Raul, he took the battery out of his cell phone, to avoid being tracked.

Popeye at Escobar's grave. December, 2015. (AFP / Raul Arboleda)

Popeye at Escobar's grave. December, 2015. (AFP / Raul Arboleda)Still fond of his patron

Conscious that a relative of one of his numerous victims can one day take revenge, Jhon Jairo Velasquez thinks he has been followed since he was freed from prison on August 26, 2014, after serving some 22 years of a 30-year sentence. As part of his early release, he is under police surveillance until early 2019.

When we get out of our taxi at the cemetery, Popeye is already waiting for us, standing in front of the Escobar vault, the final resting place for the drug lord, his parents, his younger brother, uncle, nanny and his bodyguard who was killed with him. Unlike the grave of the so-called “queen of cocaine” Grisella Blanco Trujillo, who initiated Escobar to the trade and who was killed in 2012, which has only a handful of wilted flowers, Escobar’s family vault is overflowing with splendid bouquets.

Popeye comes with a bouquet of sunflowers. Later we will see him kneel to kiss the stone.

Popeye kneels at Escobar's grave. December, 2015. (AFP / Raul Arboleda)

Popeye kneels at Escobar's grave. December, 2015. (AFP / Raul Arboleda)He greets us with typical Colombian warmth and friendliness. I expected to see a cynic with a cold stare, a caricature from a gangster movie. Instead I see a charming, smiling, amiable man, who is fascinated by firearms but who has also learned to manipulate and seduce to survive in the jungle of the drug lords and what he calls the “hell of prison.”

Still I remain skeptical. We sit on a stone bench, just steps away from the graves of three other bodyguards of Escobar.

The 53-year-old Popeye is dressed in a black polo shirt and faded jeans, with his gray hair closely cropped. I ask a first series of questions to try and understand the complexities of this man. Where was he born? What was his childhood like? When and why did he turn to crime? And of course how did he meet the man who would become his mentor?

Jhon Jairo Velasquez (Popeye). December, 2015. (AFP / Raul Arboleda)

Jhon Jairo Velasquez (Popeye). December, 2015. (AFP / Raul Arboleda)He describes his childhood in the village of Yaromal, where he was born on April 15, 1962. His father, a cattle rancher, was very strict and young Jhon wasn’t allowed to ride a bike or play with a ball on the street. He says that he didn’t want for anything except “freedom and affection.”

When he was seven, his family moved to Medellin and his world turned upside down.

“A whole new world opened up to me. In the city, I was much freer. At the time, it was already very violent. One day, seven people were killed near my house. The smell of blood, the death, it fascinated me.”

"I wanted to become an officer, not for someone to buy me a car!"

While in middle school, he began to deal drugs a bit, to hide knives at the school. He was fascinated by weapons and at first wanted to go the military route, joining the Marines. While there, the shape of his chin – which he disliked so much that he had it operated on in Miami in later years – earned him the nickname of Popeye.

He then switched to a police academy. But got disillusioned when a superior painted to him what his future was likely to be: “One day the narcos will offer you a 4X4.”

“That was really demotivating. I wanted to become an officer, not for someone to buy me a car!”

A painting named "Dead Pablo Escobar" at a museum in Medellin. (AFP/Raul Arboleda)

One day, he accompanied a local beauty to a party at Escobar’s house.

"He came out to talk to me. He had the air of a leader about him, they all know how to act around ordinary people and around animals.”

The ruthless drug lord Escobar loved animals so much that he would transform his Los Napoles hacienda into a veritable zoo. After he was killed, the hippos that he kept there would escape. They have since multiplied and haunt the surroundings of Rio Magdalena. But that’s another story…

A vet feeds one of the hippos that was kept by Escobar. July, 2008. (AFP / Raul Arboleda)

A vet feeds one of the hippos that was kept by Escobar. July, 2008. (AFP / Raul Arboleda)Popeye was 23 years old when he was first hired by Escobar, a man so rich that he at one point proposed to pay off Colombia’s debt if the government would leave him in peace to ply his trade.

“Pablo Escobar Gaviria was an assassin, a terrorist, a drug trafficker, a kidnapper, a racketeer, but he was my friend.

“He had incredible magnetism,” says his former hitman, who spent seven years working for the most feared man in Colombia.

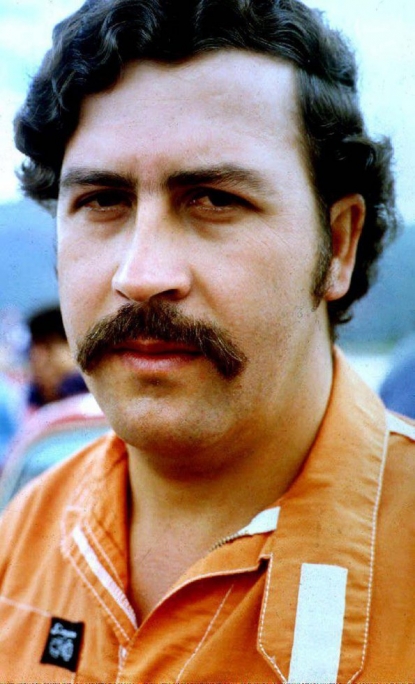

Pablo Escobar in prison, June, 1991. He and his lieutenants escaped a year later. (AFP / files)

Pablo Escobar in prison, June, 1991. He and his lieutenants escaped a year later. (AFP / files)Popeye says he doesn’t remember how many people he had killed during the “brutal war” against the rival Cali drug cartel, the Americans who wanted the druglords extradited, and against the Colombian state.

“When you reach that level, you don’t count any more. I didn’t mark a notch every time I killed someone.”

As we speak, we attract a crowd of onlookers, visitors who did not expect to find Escobar’s famous hitman at his grave. Some approach and listen as we speak, smiling at Popeye. He interrupts the interview to sign autographs (some people don’t have any paper, so he signs bills of 2,000 pesos, about 60 euro cents.) He poses with others for photos. He hugs a small girl to the delight of her mother.

Popeye poses with well wishers at Escobar's grave. December, 2015. (AFP / Raul Arboleda)

Popeye poses with well wishers at Escobar's grave. December, 2015. (AFP / Raul Arboleda)"People show me a lot of affection"

After a while, he waves goodbye to his admirers and rejoins me on the bench.

“People show me a lot of affection, they support me. Not just here,” he says.

He says he has gotten around 2,000 likes on his You Tube page "Popeye Arrepentido" (Popeye repents). He says he has turned the page and wants to find his place in society and lead a life "far away from crime.”

I am skeptical and ask him the reason for this change.

He says the transformation came in prison, where he met with a therapist once a week for eight years.

“With the psychologist, we worked on my violence. For example, each day, I had to keep notes on all the swears I said to the guards. And I said a lot! Bit by bit, I changed the way I thought, the way I acted.”

Pablo Escobar's neighborhood in Medellin, December, 2015. The druglord is still revered by many 22 years after his death. (AFP / Raul Arboleda)

Pablo Escobar's neighborhood in Medellin, December, 2015. The druglord is still revered by many 22 years after his death. (AFP / Raul Arboleda)He says that at one point he was very rich, but has since lost everything and today lives alone. He has a 21-year-old son in New York City, who was conceived when he was in a prison where detainees could meet with women.

He says that he has long been separated from the love of his life, who led him to “choose life” in July 1992, leave Escobar and turn himself in to the police.

“I am alone, waiting for death. But I believe in redemption,” he says, kissing the cross around his neck.

He says his greatest pleasure in life at the moment is to go to a corner store to buy a cold beer or an ice cream without having to account to anyone.

"Today, I am the master of my own fate"

“I wasn’t free before. First I was with Pablo Escobar, then in prison. Today, I am the master of my own fate.”

He says that when inspiration strikes, he works on a novel.

“I already have the title “The Parc of the Damned,” he says.

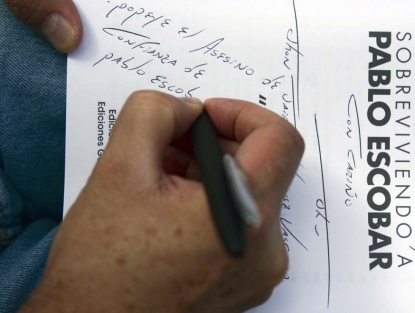

He then picks up a copy of his memoirs "Sobreviendo a Pablo Escobar" (Surviving Pablo Escobar) that I brought with me and that I had placed on the bench.

He writes “For journalist Florence Panoussian, who today at Medellin interviewed me with firmness but respect” and signs: “Popeye, the Angel of Death.”

Florence Panoussian is AFP bureau chief in Bogota. Follow her on Twitter.

Popeye signs a book about Escobar with 'Popeye, Escobar's trusted assassin." December, 2015. (AFP / Raul Arboleda)

Popeye signs a book about Escobar with 'Popeye, Escobar's trusted assassin." December, 2015. (AFP / Raul Arboleda)