The inescapable past

Paris, November 20, 2015 -- Parents owe their children certain basics: food, clothing and love. We are not supposed to inflict our pasts on them.

Standing by the window with my baby in my arms as the sound of shooting and bomb blasts came echoing over the rooftops from the Bataclan, I had the dread feeling I was adding another notch to my list of failures as a father.

She had been woken by the sirens outside and maybe our panic too as old familiar fears and feelings came flooding back.

People run in panic after thinking they heard shots near the Place de la Republique on the night of the Paris attacks on November 13, 2015. (AFP / Dominique Faget)

People run in panic after thinking they heard shots near the Place de la Republique on the night of the Paris attacks on November 13, 2015. (AFP / Dominique Faget)I grew up in the “badlands” along the Northern Irish border to the rhythm of a war that seemed as endless as the Ulster rain.

Remains of a hotel in Ulster in July, 1996, the first bombing in Northern Ireland since the IRA ceasefire two years prior. (AFP / Gerry Penny)

Remains of a hotel in Ulster in July, 1996, the first bombing in Northern Ireland since the IRA ceasefire two years prior. (AFP / Gerry Penny)A good part of my life since has been spent among people who have gone to bed wondering if their neighbours might kill them in their sleep. This is not a feeling I moved to Paris for.

An elderly couple walks near the Eiffel Tower two days after the attacks. (AFP / Valery Hache)

An elderly couple walks near the Eiffel Tower two days after the attacks. (AFP / Valery Hache)We walk the floor, the baby and I, singing lullabies and listening to France Info radio in between Twitter, and more bloody Twitter.

“Putain merde! Putain merde!” (Holy shit! Holy shit!) a hipster with one shoe howls as he limps down the street from the direction of what is now a siege. Another passes later with blood on his shirt with a girl crying hysterically into her phone, "They are everywhere, everywhere!"

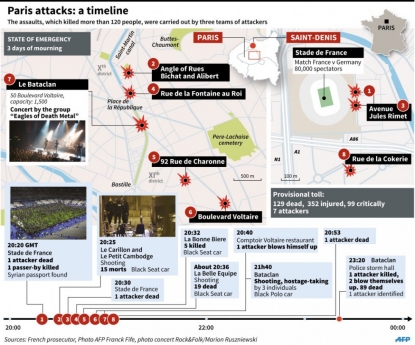

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)Soon it becomes clear the gunmen were also French. It wasn’t hard to imagine the little gits planning this for Friday the 13th -- Mullah Omar meets Freddy Krueger, the gentle irony of the band Eagles of Death Metal who were playing that night at the Bataclan going right over their heads.

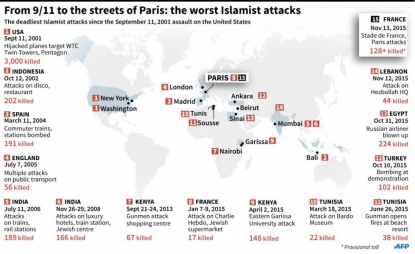

But they had us frightened, more so even than in those three days in January between the attack on Charlie Hebdo and the killings at the Hyper Cacher Jewish grocery store.

Click here to watch on a mobile device.

This was not supposed to happen in Paris, everyone said, although who were we kidding? This happens everywhere now, and we also happen to live in the Marais, the historic heart of Paris’s Jewish community, which had been targeted before.

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)Still it shook me. And it drove me mad when in the following days leaflets appeared in our building offering help to move to Israel.

The baby is finally sleeping on my shoulder, and I am about to attempt the delicate manoeuvre of lowering her onto the bed without her wake-up detonator going off.

As I lie beside her I wonder -- what if one of them gets into the building? Is there anything at hand that I could kill him with that wouldn’t wake her?

A man lies on the pavement outside the Cafe Bonne Bierre on the night of the November 13 attacks. (AFP / Anthony Dorfmann)

A man lies on the pavement outside the Cafe Bonne Bierre on the night of the November 13 attacks. (AFP / Anthony Dorfmann)France wakes on Saturday to find it is “at war”, and to the talk of “us” and “them” -- the familiar formulas I grew up with that cut the blood to the brain and harden the heart. Hateful things are already being said on the radio, a politician is making a pitch to be president again, ripping at the edges of frayed nerves.

There are no tanks. No sandbags. No barbed wire. People are not being burned out of their homes. This not Syria, nor Northern Ireland nor Cyprus in the old days, when my partner’s aunt’s windows were pulled out one night by the neighbours, angry she hadn't taken the hint and was still waiting for her husband and teenage son to come home a year after they disappeared with the rest of the men left in the village after Turkish troops invaded.

No, this is not war. That's what they want. Yet 129 people are dead.

A memorial to victims in Lyon. (AFP/Jeff Pachoud)"

“What are we doing bringing up our children here?” a neighbour asked in the freakily quiet calm of the morning. The radio is still telling people not to go out. At least one of the gunmen got away. Again. It turns out to be two.

Other than fathers and sons rushing off to synagogue, the only people on the streets of the most beautiful city in the world are tourists, clueless as ever.

Hours pass in this strange waking nightmare, a news-ticker trance which continues until the need for bread forces us out. The boulangerie is one of those bits of Morocco that has broken free from time and history, Jews and Muslims jostling each other behind the counter, laughing, arguing, teasing, flirting, impossible to tell who is who.

Myriam, who fills the whole quarter with bread and love every day, holds out her hands to me. Her eyes are wet and red but she is still trying to smile for the kids. As usual, she slips my eldest a chouquette.

Parisians may be rude, exasperatingly so to visitors, and to each other when it suits, but I cannot walk 100 steps from my front gate without having to say good day, kiss and smile at a minimum of a dozen people, and give at least one beggar his due.

German pianist Davide Martello pulls his piano with his bicycle to play "Imagine" outside the Bataclan concert hall the day after the attacks. (AFP/Valery Hache)

What do we tell the children? Whatever you say, say nothing, we Irish like to say. For me The Troubles (what our war was called until it was over) was driving at night on empty roads counting the bends home as the tit-for-tat of who had tried to kill whom that day came over the radio.

It did me no harm, as we always say about things that did.

Things I remember when I was six, my eldest’s age. Bloody Sunday and bargain hunting with my mother at bomb sales at the bottom of the street where the army stopped the civil rights march that day, and how the smell of smoke and ammonia never quite left those clothes. The chip shop being blown up. My father dragged from the car and humiliated by a soldier -- the belief that he could protect me left on its arse next to him on the ground.

Somewhere inside I never forgave him for not putting up a fight until 12 years later I came upon a part-time farmer like him shot at the side of the road for the crime of collecting dog licences for the British Crown, his shovel by his side.

It wasn't until I left that I realised what a fearful, paranoid little bubble we were living in. Cross the invisible frontier that runs down a street and you were prey. Even gravity sat heavier there, just as it does now in Paris, and everything and everywhere else felt frivolous and unreal.

A British soldier drags a Catholic protester during the "Bloody Sunday" killings in January, 1972. (AFP/Thopson)

Under a bright sunshine that was in perfect contrast to the mood of the city, I met Helene, who had brought her four-year-old Jeanette to Place de la Republique -- which also became of symbol of shared grief and solidarity after the Charlie Hebdo attacks -- to explain to her why everyone was so sad. She had earlier sat her two older boys around the table to talk to them about Islam and France’s difficult history with Algeria and where this murderous anger might come from.

A girl lights a candle in front of the broken window of "Le Carillon" restaurant. (AFP/Loic Venance)

She was exactly the sort of clear-eyed public-spirited person who gives France its backbone. But even she feared the worst, warning that if Muslims did not demonstrate massively their repugnance at what had happened, there would be consequences. "I am afraid of what will happen... It will burn," she said, clearly shocked at herself.

As we said our goodbyes I noticed a man crying and realised he had heard some of what was said. Mehdi, a Muslim refuse collector, said he and his wife had hardly slept since Friday with shock and fear. “We are French too… I was born here and so were my children.”

"Not in my name (from a Muslim)" reads a note held during a memorial to the vicitims of Paris attacks in January, 2015. (AFP/Kenzo Tribouillard)

In 1989 I fell in love in and with Sarajevo. Prosperous and sophisticated, almost everyone seemed to come from a religious mix that would get you killed three times over back home.

I had no idea such a thing as European Islam existed, nor how at home Ottoman mosques looked in those deep green valleys.

I wished we could be more like them. But a year later they were just like us. But worse, much worse. Sarajevo was “the Paris of the Balkans”. Things can and do fall apart.

A destroyed mosque in Ahinici, northwest of Sarajevo, in April, 1993. (AFP / Pascal Guyot)

A destroyed mosque in Ahinici, northwest of Sarajevo, in April, 1993. (AFP / Pascal Guyot)I hope it will take more than a handful of self-loathing petty criminals in search of redemption to drive France to civil war. These guys cannot threaten France unless it wants to rip itself apart.

Cellist Vedran Smailovic plays Strauss in the bombed-out National Library in Sarajevo in September, 1992. (AFP / Michael Evstafiev)

Cellist Vedran Smailovic plays Strauss in the bombed-out National Library in Sarajevo in September, 1992. (AFP / Michael Evstafiev)My heart sank when I saw soldiers on the streets after the January attacks, standing outside little Jewish yeshivas and community centres you never knew were there. They are back again after these attacks.

French security forces patrol the Jewish quarter in Paris following Islamist attacks in January. (AFP / Bertrand Guay)

French security forces patrol the Jewish quarter in Paris following Islamist attacks in January. (AFP / Bertrand Guay)But soldiers on the street don't just not work, they actively create insecurity, suspicion, division and finally hatred. I know, I grew up around them. Our miserable little war dragged on for nearly 30 years because of the alienation the "security problem" created.

Riot police in Belfast, January, 2013. (AFP / Peter Muhly)

Riot police in Belfast, January, 2013. (AFP / Peter Muhly)Heavy security measures will not be enough to stop them killing, but they may create anger that could bring the jihadis the tiny number of recruits they need.

Masked French policemen in the Paris suburb of Saint-Denis as security forces raided an apartment in an operation targeting the mastermind of the attacks. (AFP/Kenzo Tribouillard)"

Much poison has been poured into French political discourse of late, and more people don’t mind the taste. Anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim rhetoric has been dominating the forthcoming regional elections, with the mayor of Nice on the Cote d'Azur banning North African women ululating after weddings at his town hall, while another mayor in a suburb of Paris -- mindful of the electoral threat from the far right -- now insists on pork being served twice a month in its schools regardless of its Jewish and Muslim children.

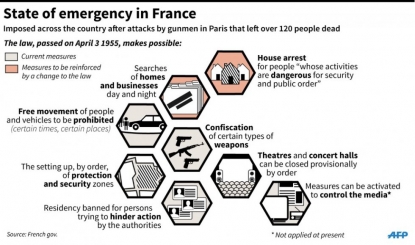

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)Paris is numb now, and we are easy prey to anger and tears. My heart like everyone else’s is bursting. The loss is terrible. Fourteen people died on the terraces of the Petit Cambodge and the Carillon cafe that face each other across a corner of the 10th arrondissement that is the epitome of trendy multicultural Paris. I used them both and was probably the best customer of the gluten-free patisserie next door.

I have never before felt the emotion, sincerity, and togetherness here that I felt standing there on Sunday trying not to look at the little piles of bloodstained sand where the victims fell. On the wall above one of these patches -- maybe where the Algerian architect died (how cretinous these gunmen were) -- a local graffiti artist has postered her little two-tone Alice in Wonderland character holding a candle.

Flowers pile up on the sidewalk outside of the Belle Equipe restaurant. (AFP / Bertrand Guay)

Flowers pile up on the sidewalk outside of the Belle Equipe restaurant. (AFP / Bertrand Guay)It’s heartbreaking and heart-stopping too in its affirmation of that great French quality of honouring even the most awful by trying to make it beautiful.

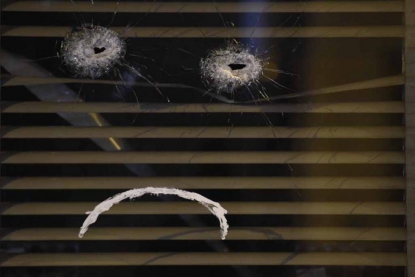

Windows of the Belle Equipe restaurant a day after the attacks. (AFP / Lionel Bonaventure)

Windows of the Belle Equipe restaurant a day after the attacks. (AFP / Lionel Bonaventure)The writing on the walls has been equally and typically fantastic, “Let’s be united” has been sprayed opposite my kitchen window, with graffiti in a more stylish hand around the corner saying, “Changez. Aimez” (Let’s change, let’s love) and “Violence craves reaction”.

Not all, however, lifts the spirits. A “France for the French” sticker was plastered over the face of a woman in a headscarf on a poster for an exhibition of Arab photography at our local town hall.

“Meme Pas Peur” (Not even afraid) — a schoolyard retort to someone trying to scare you — is the one you find most often though, particularly at the statue of Marianne, the woman who symbolises the values of liberty, equality and fraternity, which has become a shrine to the victims at the Place de la Republique.

A "Not even afraid" sign on Republique in the days after the attacks. (AFP/Patrick Kovarik)

People have been coming since Friday night to pray or look at the tributes. With crowds walking around it night and day in silent reverence, it has taken on something of the Kaaba in Mecca.

Place de la Republique at night two days after the attacks. (AFP / Joel Saget)

Place de la Republique at night two days after the attacks. (AFP / Joel Saget)Whatever the graffiti says, people are afraid. And they should be, said Meir, an Orthodox Jew whose family survived Auschwitz. “They are going to come for us again. We should be afraid. They will never stop killing us.”

A few hours after we talked several people were slightly hurt in a panic at the monument when someone threw a firecracker. Something similar happened at the Carillon and the Petit Cambodge.

Half an hour later my daughter walked into a wave of frightened people fleeing down our street looking for somewhere to hide after an Australian tourist mistook an armed plainclothes policeman for a terrorist. One of her little friends was dragged into a cafe by his mother who threw herself over him on the floor, before hiding in the basement with the rest of the panicked customers. I hope he doesn’t remember that fear.

Police move in as panic spreads following a false alarm on Place de la Republique two days after the attacks. (AFP / Joel Saget)

Police move in as panic spreads following a false alarm on Place de la Republique two days after the attacks. (AFP / Joel Saget)The next day after school she told me the teacher had told them that “the soldiers of Paris were now attacking the baddies’ country... They attacked Paris because they don’t like our liberty,” she added, sounding for all the world like George W Bush.

Control room at a French military base in the Gulf, as operations against Islamic State in Syria and Iraq are underway. (AFP / Karim Sahib)

Control room at a French military base in the Gulf, as operations against Islamic State in Syria and Iraq are underway. (AFP / Karim Sahib)So this is where we are now, sleepless and shaky, worried by trauma tumbling down the generations, but trying not to show it.

How can we defeat the Islamic State, someone on the radio despairs, how do you defeat madness? By being sane of course.

The cue for how we should proceed was set for me by someone whose strength I can only marvel at. Journalist Antoine Leiris lost his life wife Helene Muyal at the Bataclan. In an open letter to the gunmen he wrote while his baby son was having his nap, he told them, “You will not have my hate… We two, my son and I, are stronger than all the armies in the world. I cannot waste any more time on you as he has just woken from his sleep. He is only just 17 months old, he is going to eat his snack just like every other day, then we are going to play like every other day, and all his life this little boy will defy you by being happy and free. Because you will never have his hatred either.”

Fiachra Gibbons is an AFP journalist based in Paris, where he has lived for eight years. Follow him on Twitter.

The Eiffel Tower lit up in the French tricolor in the days following the attacks. (AFP / Bertrand Guay)

The Eiffel Tower lit up in the French tricolor in the days following the attacks. (AFP / Bertrand Guay)