Remembering New Orleans chaos, 10 years after Katrina

CHICAGO, August 27, 2015 - Ten years ago, my New Orleans hotel shook like a speeding freight train.

Hurricane Katrina's deadly winds tore up roofs, yanked trees from the ground, and pushed towering walls of seawater miles past the coast.

I am still haunted by what I saw as the Big Easy collapsed into chaos.

A dead man lay slumped in a chair outside the New Orleans convention center, his elderly body covered in a yellow blanket.

A sea of hungry and thirsty people sat nearby, their faces sunken in defeat and despair as they waited day after day for help to arrive.

The bodies of two hurricane victims remain at a door of the New Orleans Superdome on September 2, 2005 (AFP Photo / Robert Sullivan)

The bodies of two hurricane victims remain at a door of the New Orleans Superdome on September 2, 2005 (AFP Photo / Robert Sullivan)An exhausted mother limped barefoot across a metal bridge as she clutched her five-day-old baby and told me of a frantic escape across a plank and through a neighbor's window as the floodwaters swallowed her home.

A squad of heavily-armed soldiers -- who had been given shoot-to-kill orders -- marched into the glow of our headlights as we drove through the pitch-black French Quarter.

More than 1,800 people were killed after Katrina ravaged the US Gulf Coast on August 29, 2005. Most of the dead were in New Orleans.

Soldiers patrol the French Quarter in New Orleans on September 4, 2005

(AFP Photo / Nicholas Kamm)

Some 80 percent of the low-lying city was engulfed by filthy water that rose as high as 20 feet (six meters) after badly-maintained levees burst under the pressure of a massive storm surge. It came up so fast some poor souls drowned in their homes.

Tens of thousands of people were trapped when the city became a sweltering swamp. Hundreds were stuck on rooftops. Those who made it to dry land sweated it out on the freeways or in ill-equipped emergency shelters.

A man waits to be rescued from a roof as flood waters continue to rise on September 2, 2005 in New Orleans (AFP Photo / pool / Robert Galbraith)

A man waits to be rescued from a roof as flood waters continue to rise on September 2, 2005 in New Orleans (AFP Photo / pool / Robert Galbraith)People became increasingly desperate and fearful as looting and (what turned out to be mostly false) rumors of rampant violence hampered relief efforts.

Supply trucks didn't arrive with food and fresh water until the fifth day.

Those five days felt like five years.

Rooftops barely visible

Freelance photographer James Nielsen and I slipped out of our hotel not long after the eye of the storm passed on Monday morning, bracing ourselves against buildings as we looked for signs of damage amid the pounding rain and powerful wind.

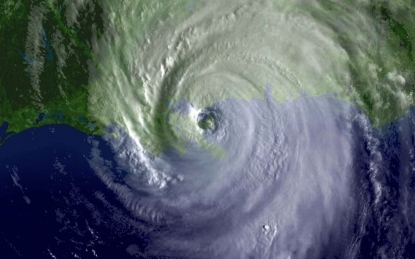

A satellite image shows Hurricane Katrina as it makes landfall on August 29, 2005

(AFP Photo / NOAA)

The older parts of New Orleans -- the French Quarter, Garden District, and central business district -- escaped the worst of Katrina's wrath because they were built on higher ground. So it took a few hours for us to understand how bad things were.

My heart sank when we pulled up behind an ambulance parked on a freeway overpass and I realized the triangles poking out of the water were rooftops.

A resident uses a board to paddle through flood waters in New Orleans on August 30, 2005

(AFP Photo / James Nielsen)

We watched a boat pull up to a man paddling a pontoon made of wooden shipping pallets and then turn towards a nearly submerged house. I couldn't believe my eyes as I watched them pull an elderly man out through his window. When the boat was full, it swept up to the firefighters waiting on the freeway with a ladder. The elderly man was soaking wet and shivering despite the heat. Another passenger told me that the water came up so fast he only had time to grab a hammer and a screwdriver as he scrambled up into his attic. He used them to pound a hole through his roof. Without them, he may never have gotten out.

We woke Tuesday to find that the water had risen even higher after a canal was breached.

Flood waters from Hurricane Katrina cover a cementery on August 30, 2005 in New Orleans (AFP Photo / pool / Vincent Laforet)

Flood waters from Hurricane Katrina cover a cementery on August 30, 2005 in New Orleans (AFP Photo / pool / Vincent Laforet)Nielsen and I followed a military convoy to a bridge leading into the flooded Lower Ninth Ward. He talked his way onto a boat and I talked to the people being dropped off on dry land. That's where I met the young mother with her hungry newborn. I also spoke to a woman who saw her husband get swept away by the storm surge as they tried to reach shelter. Sobbing, she asked me where to go to find his body. I didn't know then, and I don't know now if she ever found him.

We saw some looting in the French Quarter, but the mood remained relatively festive that day.

Rug store owner Bob Rue speaks in front of his shop adorned with graffiti warning looters away in New Orleans on September 4, 2005 (AFP Photo / Nicholas Kamm)

Rug store owner Bob Rue speaks in front of his shop adorned with graffiti warning looters away in New Orleans on September 4, 2005 (AFP Photo / Nicholas Kamm)I found a restaurant that was serving warm beer and hot gumbo: the power was out, but the gas stove was still working and they wanted to cook up all their food before it spoiled. I spoke to residents with barbecues who were doing the same that night.

Despair, desperation, fear

The mood darkened on Wednesday.

People grateful to be rescued from their flooded homes had found themselves dumped at the downtown convention center with no food, water, medical attention or functioning toilets. A fire broke out in a looted shoe store on flooded Canal Street. Hotels were kicking out their guests.

Frightened, thirsty people fled rumors -- mostly false -- of mayhem and violence and camped out on the freeways under a punishingly hot sun.

Thousands of people displaced by Hurricane Katrina await buses to depart the Superdome on September 2, 2005 in New Orleans, Louisiana (AFP Photo)

Thousands of people displaced by Hurricane Katrina await buses to depart the Superdome on September 2, 2005 in New Orleans, Louisiana (AFP Photo)A shell-shocked intensive care nurse told me how medical evacuation helicopters carrying babies were grounded by the sound of gunfire.

Thursday was a nightmare. I spent the morning talking to refugees on the freeway who kept asking me how the US government could send help across the world but could not manage to take care of its own citizens. I saw bodies floating in the water below.

Then I waded through the foul floodwaters to check on the evacuation of the Superdome, a sports arena used as an emergency shelter where 26,000 people had been trapped with scant supplies. The stench of urine and feces was unbearable.

A baby is passed above the crowd as people wait to leave the Superdome in New Orleans on September 1st, 2005 (AFP Photo / James Nielsen)

A baby is passed above the crowd as people wait to leave the Superdome in New Orleans on September 1st, 2005 (AFP Photo / James Nielsen)People were so desperate for help that babies were being passed forward over the throngs pressing up against the barricades to get out. I wept at that memory this week and still cannot believe I saw it happen in America.

On Friday, a tough-looking sheriff's deputy broke down into tears as he told me of inmates who drowned in their cells or got caught in razor wire after trying to jump out of the flooded prison. He could not understand why the deputies and their families were left behind to spend Thursday night on a freeway after the prisoners were evacuated. While we were talking, a helicopter landed nearby. Help had finally reached him.

A US Army soldier and a New Orleans deputy sheriff direct stranded people to board a helicopter on near the Superdome in New Orleans on September 2, 2005 (AFP Photo / Nicholas Kamm)

A US Army soldier and a New Orleans deputy sheriff direct stranded people to board a helicopter on near the Superdome in New Orleans on September 2, 2005 (AFP Photo / Nicholas Kamm)The city transformed into an armed camp on Friday. Thousands of troops poured in and with them came supply trucks full of food and water and buses to ferry people out of town.

‘God help us’

I stayed another week as the military managed to restore order and evacuate all but the most stubborn residents. But I didn't sleep easily until long after I got home.

On Saturday I cowered on the filthy ground outside the Superdome after a sniper opened fire nearby. A colonel managing the evacuation shook his head and told me "as this deteriorates those guys are going to be out more and more."

A woman in shock is helped by Louisiana National Guardsmen after gunshots were heard at New Orleans Superdome on September 1st (AFP Photo / Robert Sullivan)

A woman in shock is helped by Louisiana National Guardsmen after gunshots were heard at New Orleans Superdome on September 1st (AFP Photo / Robert Sullivan)Later that day I stumbled across a makeshift jail in the bus depot shortly after the first post-Katrina prisoner was booked. The state's chief of corrections was supervising a crew of prisoners bussed in to help build it. He told me that until that point police hadn't bothered to arrest anyone because "there was no place to put them."

On Sunday, I paid my respects to one victim whose body was entombed with fallen bricks and a white sheet bearing the words: "Here lies Vera. God help us."

In the week that followed, I covered the desperate efforts to rescue remaining survivors and the grim search for bodies. I followed crews picking up pets, spoke to people who stubbornly refused to leave their homes, and spent too much time at the 'bar that never closes'.

John Barnes, 50, and his cat Patches wait to be evacuated from the Superdome in New Orleans on September 3, 2005 (AFP Photo / Nicholas Kamm)

John Barnes, 50, and his cat Patches wait to be evacuated from the Superdome in New Orleans on September 3, 2005 (AFP Photo / Nicholas Kamm)I finally got a hot shower at the airport command center -- my first in nine days -- but was chilled by the matter-of-fact tone of a Federal Emergency Management Agency spokesman who told me that a lot of the bodies may never be found because "alligators love that type of stuff."

I knew things were getting weird when I ran into Sean Penn bailing water out of his boat with a plastic cup as he tried to join in rescue efforts.

And I longed for clean, dry socks.

Life-changing experience

I have returned to New Orleans many times to report on its recovery from Katrina and then on the impact of the BP oil spill. I even managed to learn to love the Big Easy.

But those first five days changed me.

I was a cub reporter when my editors sent me to cover Katrina.

I lost my faith in government and am still angry about the people who suffered or died because of the botched response.

I found my faith in humanity deepened by the countless acts of selfless bravery and kindness that I witnessed -- like the man who spent days ferrying his neighbors out of the flood zone and wouldn't waste a minute to talk to a reporter.

I never learned his name.

Mira Oberman is an AFP journalist based in Chicago. Follow her on Twitter.

A man clings to the top of a vehicle prior to being rescued by the US Coast Guard from the flooded streets in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans on September 4 , 2005

(AFP Photo / pool / Robert Galbraith)