A summer of fire in Sarajevo

PARIS, August 11, 2015 - June 1995: summer was just beginning in Paris when I was called over to the editor-in-chief's desk. AFP was urgently looking for someone to run the bureau until September in war-ravaged, besieged Sarajevo. Naturally I accepted, though I knew the mission would be tough.

Just a few days earlier, special correspondent Christian Millet had arrived in Bosnia to do the job that I was now being offered. But he was wounded in a shelling by Serb forces that thrust AFP's armoured car into a ditch. My editors needed to replace him immediately.

I had worked with the Belgrade bureau to cover the start of the Slovenian war four years earlier, leading up to the Brioni Agreement in 1991. As the conflict spread in the region I travelled to Croatia, where I covered the battles of Sisak and Osijek.

But this would be my first time in Bosnia and two days after my meeting at AFP, I was in a car crossing Herzegovina.

First we passed Mostar, whose historic centre and 16th-century Ottoman bridge had been destroyed in fighting between Bosnian Muslim forces and Croats from the region.

I then travelled over Mount Igman, taking the only route into besieged Sarajevo.

AFP reporter Christian Millet (bottom) and Vincent Hugueux of French magazine "L'Express" lie injured on June 1995 after their armored car, hit by Bosnian Serb fire, turned over on the Mount Igman road. The author of this picture, Eric Cabanis, was also slightly injured (AFP Photo / Er)

AFP reporter Christian Millet (bottom) and Vincent Hugueux of French magazine "L'Express" lie injured on June 1995 after their armored car, hit by Bosnian Serb fire, turned over on the Mount Igman road. The author of this picture, Eric Cabanis, was also slightly injured (AFP Photo / Er)By the time my mission began, Sarajevo had been under siege for three years and the situation was completely deadlocked.

I didn't know it at the time, but I would soon end up witnessing the beginning of the end of Bosnia's war.

Three years under bombing

When I arrived in Sarajevo, tens of thousands of people -- Bosnian Muslims and Serbs -- were struggling to survive despite the bombings and sniper fire.

The summer sunshine had brought new life to the land amid the ruins, but for three years, Sarajevo's residents existence had been a monotony of suffering and loss.

They would watch as columns of smoke rose into the sky from the incessant shelling that targeted their water wells, the central market and even the hospital. The purpose of the bombings was to terrorise the population and force them to flee.

The sister of a Bosnian Croat soldier killed on the frontline in Sarajevo grieves at her brother's funeral on August 7, 1995 (AFP Photo / Fehim Demir)

The sister of a Bosnian Croat soldier killed on the frontline in Sarajevo grieves at her brother's funeral on August 7, 1995 (AFP Photo / Fehim Demir)In early June, in a doomed bid to loosen the Serb forces' siege on the city, Bosnian Muslim forces launched an offensive, but that only prompted even fiercer bombings in retaliation.

UN peacekeepers were deployed in the city but the international community's priority at the time was to stop the conflict from spreading to other countries in the region. So long as the fighting didn't spill over beyond the surroundings of battered Sarajevo, the world didn't seem to care.

When the bombing increased, Britain and France finally decided to send in a rapid reaction force armed with tanks, heavy mortars and 155 mm cannon, with a mandate to protect the Blue Helmets.

So I spent the start of my mission following up on the excruciatingly slow cannon arrivals. Once in place, they could target Serb positions on the other side of the city, 12 kilometres (seven miles) away, with high precision.

For Sarajevo residents, desperate for hope, this was a good sign.

A Sarajevo morgue worker checks the identification tags of shelling victims on June 16, 1995 (AFP Photo / Fehim Demir)

A Sarajevo morgue worker checks the identification tags of shelling victims on June 16, 1995 (AFP Photo / Fehim Demir)The AFP bureau was not housed in an office or an apartment, but in a basement in the city centre that had once been a pizzeria.

Bizarrely enough, there were still menus lying around on the tables. But the empty bar and sacks of rubble stacked up against the door, to protect us from the impact of the bombings, were stark reminders of how much life had changed here.

And while special correspondents like Christian and I could come and go, our local journalists had lived through the siege from the very beginning.

Our photographer Fehim Demir had been forced out of his neighbourhood, Dobrinja, early in the war. He struggled for months to find new equipment and start working again.

Our cook worried about her son, a Bosnian Muslim living in Belgrade, where she feared he could be forcibly recruited into the Yugoslav army and sent to the front line.

A whoman whose husband was wounded by a shell leaves Sarajevo's Kosevo hospital with her children on July 21, 1995 (AFP Photo / Joel Robine)

A whoman whose husband was wounded by a shell leaves Sarajevo's Kosevo hospital with her children on July 21, 1995 (AFP Photo / Joel Robine)I remember the arguments we would have in the office over the exaggerated death tolls published by Bosnian Muslim authorities. The UN would publish its own toll too, but only several hours later.

I remember Schtock, a local spirit that Sarajevo residents would secretly smuggle into the city through a tunnel that ran under the airport. One had to share a glass with the smugglers to keep them happy, and therefore ensure a constant supply.

I remember the elderly linguist Ksenija Crvenkovic who translated Albert Camus's posthumous novel "The First Man" from French into Serbo-Croat -- one of the very few books, if not the only one, published that year in Sarajevo.

Translating Camus in Bosnia in 1995 felt like a true act of heroism, so on a day of relative calm I sat down to write a feature about her.

But the very next day, breaking news took over.

Second market massacre

A little before midday on August 28, shells began raining on Markale market in the heart of Sarajevo, killing 37 people and wounding some 100 others.

I rushed to the scene and saw rescuers pulling victims' bodies out of the rubble. The stench of death and gunpowder filled the air. It was practically impossible to breathe.

Nothing made sense: people had come to the market to buy groceries when goods were scarce. Those killed and wounded were simply at the wrong place at the wrong time.

A police officer stood over the bodies, flipping through passports and driving licenses, gazing at photographs of smiling faces to identify the bodies. Many of the victims were women and children. Even in Sarajevo, where death had become routine, this particular bombing felt like a turning point.

A French 155mm gun on Mount Igman on August 30, 1995 (AFP Photo)

A French 155mm gun on Mount Igman on August 30, 1995 (AFP Photo)The Markale market had already suffered a massacre a year and a half earlier, with 68 dead and 144 wounded.

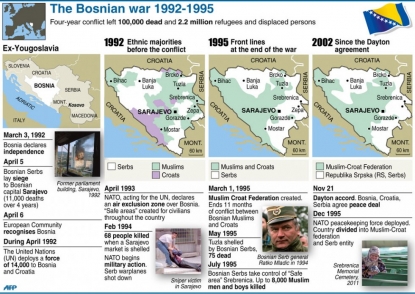

And in the worst massacre in Europe since World War Two, 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys had been executed by Serb forces in Srebrenica that summer.

A UN peacekeeper from France arrived at the market and started gathering witness testimony.

"Pay attention to what you are about to say, it might have significant consequences," he warned traumatized survivors.

Bosnian Serbs frequently accused Muslims of bombing their own population to provoke an intervention by NATO forces, so it was important to investigate and determine the source of the fire.

But this time round, the culprits were quickly identified.

NATO launched a vast aerial campaign two days later targeting Serb military positions and weapons depots around Sarajevo, with cannon providing ground support.

Serb forces started falling back, with long lines of armored vehicles retreating in the following days to Serbia. I spent several nights on the streets, watching the explosions light up the sky as I tried to figure out the warplanes' targets.

Leaving Sarajevo

In early September, I left Sarajevo by road with two French journalist friends, as a little civilian plane landed for the first time in a long time in the airport.

In December the Dayton Agreement put an end to fighting, and two months later Bosnia officially declared the lifting of modern history's longest siege.

But the violence would not end there; instead it shifted to Kosovo.

UN tank trucks deliver water on July 23, 1995 in Sarajevo (AFP Photo / Joel Robine)

UN tank trucks deliver water on July 23, 1995 in Sarajevo (AFP Photo / Joel Robine)Twenty years on, two thoughts linger in my mind.

First, these extraordinary, historic events that we cover don't necessarily leave much of a trace. This dawned on me recently, when I returned to Sarajevo to give a talk about my experience to a group of journalism students.

I quickly realised that for this new generation of reporters, an eternity had gone by since the end of the Bosnian war. They must have felt like I did whenever I heard about the Algerian war when I first started at AFP. I might as well have told them I'd reported from the trenches of World War One or from Berlin during the Reichstag fire in 1933. The Bosnian war was history.

It was a healthy reality check for a journalist.

A woman takes cover behind a car as snipers open fire in downtown Sarajevo on June 14, 1995 (AFP Photo / Anja Niedringhaus)

A woman takes cover behind a car as snipers open fire in downtown Sarajevo on June 14, 1995 (AFP Photo / Anja Niedringhaus)But Sarajevo also taught me another, deeper lesson.

In 2010, I spent several weeks working with a photographer in eastern Afghanistan, covering the International Security Assistance Force's operations.

The setting was as miserable as wartime Bosnia, if not more so, with temperatures soaring above 40 degrees Celsius.

Frequent attacks in the area had killed and wounded hundreds of Afghan civilians. It was also a bad year for France, with 15 troops killed and dozens more wounded.

The situation appeared just as desperate as in Sarajevo 15 years earlier.

A Bosnian soldier crosses a protected bridge over the Dobrinja river, south eastern Sarajevo, on June 25, 1995 (AFP Photo / Pierre Verdy)

A Bosnian soldier crosses a protected bridge over the Dobrinja river, south eastern Sarajevo, on June 25, 1995 (AFP Photo / Pierre Verdy)But a non-commissioned officer told me: "Look! Ten years ago I was in Kosovo. I thought that would never end either. Now, I'm going on holiday with my wife."

It's hard to admit it, but the soldier was right. Life goes on even after the worst wars.

The following summer, I returned to Mostar, and I was really moved by what I saw there. The Bosnians had restored everything, including the Stari Most bridge, inaugurated once again more than 450 years after it had first been built.

I also saw people lounging on terrace cafes on streets that had once been reduced to rubble and where only stray dogs dared wander.

It was as though the war had never happened. Life had defeated it.

Dominique Chabrol, on assignment in Sarajevo in 1995, is currently covering French politics at the AFP headquarters in Paris. This post was translated by Serene Assir in Paris. Click to read the original French version.

A Bosnian high diver jumps from the 'Stari Most' during a competition in Mostar on July 26, 2015 (AFP Photo / Elvis Barukcic)

A Bosnian high diver jumps from the 'Stari Most' during a competition in Mostar on July 26, 2015 (AFP Photo / Elvis Barukcic)