Long march to the scaffold

AFP correspondent in Islamabad

ISLAMABAD, August 8, 2015 -Shafqat Hussain was hanged on Tuesday morning before dawn prayers after languishing for a decade on death row. His name probably means nothing to you. Or not very much.

A Pakistani, hanged or not, whatever. And yet his death was intertwined with a tragedy that the world claimed to share with Pakistan: the Peshawar massacre.

On December 16 last year, Taliban gunmen brought carnage to a military-linked school in Peshawar, in northwestern Pakistan, systematically killing students and teachers one by one. The bloodiest attack in the country's history raised questions of human nature itself: how can anyone shoot children so cold-bloodedly?

For Pakistan, two words followed: never again. For a country so often left grieving by Islamist attacks, Peshawar was a bloodbath too far, a national drama against which everything else - before and since - would be judged.

Volunteers take the body of Shafqat Hussain to a mortuary after his execution in Karachi on August 4, 2015 (AFP Photo / Asif Hassan)

Volunteers take the body of Shafqat Hussain to a mortuary after his execution in Karachi on August 4, 2015 (AFP Photo / Asif Hassan)In the aftermath of the attack, the government made an announcement that was both popular and uncompromising: it would lift the moratorium on the death penalty which had been in force since 2008. And one of the first names on the list of men to be executed was that of Shafqat Hussain.

His connection with Peshawar? None except that the bloodbath led to his death.

Ten Years of Solitude

On the day the Taliban attacked the school in Peshawar, Shafqat Hussain was sitting in the central prison in Karachi at the far end of the country for a crime dating back to 2004.

At the time, this "chowkidar", or nightwatchman, who had left the green valleys of his native Kashmir to work in the teeming southern metropolis, was accused of the murder of Umair, a seven-year-old boy who had gone missing. The boy’s father said he had received a phone call demanding a hefty ransom.

A classroom of the school attacked by the Taliban in Peshawar (AFP Photo / A. Majeed)

A classroom of the school attacked by the Taliban in Peshawar (AFP Photo / A. Majeed)Forty-one days later, Shafqat was arrested and the body of the young Umair found in a plastic bag in a gutter. An anti-terrorism court heard the case. Why an anti-terrorism court? Because Umair’s death created a wave of panic in the Karachi area and thus terrorised the population, according to justice officials.

Shafqat confessed to the killing -- but only after nine days of police torture, according to his lawyers. The court handed down a death sentence. Besides the circumstances surrounding his confession, another factor - initially ignored - eventually began to emerge: his age.

His relatives said he was 15 at the time of the killing, or even 13, according to other documents submitted by his supporters in court or to the government - a crucial detail since Pakistani law and international treaties ratified by Islamabad prohibit the death penalty for crimes committed by minors.

Shiite students protest against the Peshawar attack in Karachi (AFP Photo / Asif Hassan)

Shiite students protest against the Peshawar attack in Karachi (AFP Photo / Asif Hassan)Far from the public eye, the case went to the Supreme Court, where prosecutors argued that Umair had regularly visited Shafqat. On the fateful day, the pair went to see a rabbit together in someone’s flat, lawyers said. When Umair wanted to go home, Shafqat tried to stop him and hit a stick on a wall.

“Unfortunately it hit on the head of the child as a result whereof he fell down," the court ruled, confirming the death sentence despite the killing not being premeditated and doubts surrounding both Shafqat’s confession and his age.

According to the court, Shafqat Hussain later threw the body in a gutter and called the family to demand a ransom, but in return for what - a dead body? The story remains unclear.

A $1 billion hanging

Although the death penalty was confirmed, the sentence wasn’t carried out.

In 2008, with the arrival of the civilian government of Asif Ali Zardari, the widower of Benazir Bhutto, following years of military rule, Pakistan imposed a moratorium on capital punishment. Five years later, in 2013, rumours emerged of plans to resume executions with the election victory of Nawaz Sharif, considered to be more hardline on the issue.

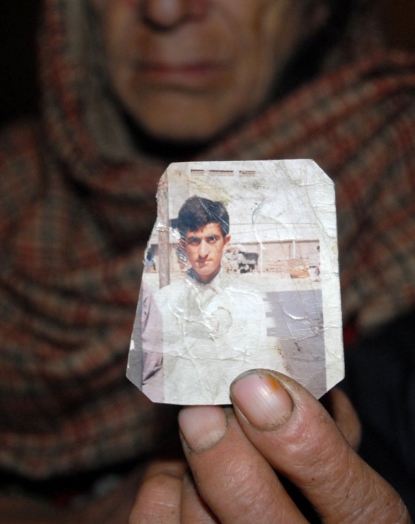

The parents of Shafqat Hussain display a picture of their son in March 2015 (AFP Photo / Sajjad Qayyum)

The parents of Shafqat Hussain display a picture of their son in March 2015 (AFP Photo / Sajjad Qayyum)I then tried to find out about juvenile prisoners on death row in Pakistan who might face execution if the government decided to bring back capital punishment. In short, what does it look like when someone is waiting to die, far from home, deep inside a Karachi prison? How do they make any sense of anything? How do they keep hope alive?

The subject seemed even more interesting since the European Union was considering easing trade tariffs in order to boost textile exports and thereby help employment and stability.

Would defending human rights once again be sacrificed on the altar of "good relations" and trade? Or from a utilitarian point of view, would the jobs created in the textile industry be considered more important than the execution of convicted prisoners?

A protest against the planned execution of Shafqat Hussain in Islamabad on March 18, 2015 (AFP Photo / Aamir Qureshi)

A protest against the planned execution of Shafqat Hussain in Islamabad on March 18, 2015 (AFP Photo / Aamir Qureshi)That was when a contact tipped me off about the case of Shafqat Hussain and gave me access to his legal papers - the start of my immersion into the mysteries of the justice system in Pakistan, where the rich can be reborn, like a phoenix rising from the ashes, after a stint behind bars.Just ask Asif Ali Zardari, who spent a decade in prison before becoming president.

But the poor, who often have no such political connections and are sometimes undocumented, can be sentenced in the shadows, on the basis of confessions forcibly extracted by police. And they are seldom reborn.

So I went with some colleagues to Karachi’s central jail to try to meet Shafqat Hussain, to put into words - his words - what it’s like to spend a decade on death row.

But despite sipping tea at a number of local ministries while trying to get authorisation to meet him, the answer always came back the same: nahin! No! The reason? Security. It was because the prison held members of Al-Qaeda - or so went the argument. Admittedly some of those prisoners later tried to escape by digging a tunnel under the prison in an episode that could have been inspired by a Hollywood screenplay.

The ambulance carrying the dead body of Shafqat Hussain leaves the Karachi prison (AFP Photo / Asif Hassan)

Without access to the prison, the story was finished. Especially since Nawaz Sharif decided to keep the moratorium. And for good reason. Pakistan was just about to be granted trade status with the catchy name of GSP+ that would enable it to sell its textiles in Europe without paying any tariffs in exchange for commitments to respect human rights.

"You'll see,” one human rights activist told me, “as soon as there’s a major crisis, the calls to bring back capital punishment will grow." I didn’t believe him but his prediction proved prophetic.

Heads will roll

After the attack in Peshawar, heads had to roll. The whole nation, from its innocent children to its powerful military, had been hit like never before. Death row inmates do not attract much sympathy, especially from a population that has been pummelled by violence and wants only one thing - for it to stop.

Shortly after the announcement that the moratorium would be lifted, the name of Shafqat Hussain cropped up again, this time on the list of the first to be executed. I still had my files on the story and I got straight to it. After the first stories appeared in the local and international media the Pakistani government decided to grant a stay of execution.

Relatives of Shafqat Hussain look at his body at a mortuary in Karachi on August 4 (AFP Photo / Asif Hassan)

Relatives of Shafqat Hussain look at his body at a mortuary in Karachi on August 4 (AFP Photo / Asif Hassan)But the executioners had well and truly gone back to work. More than 180 death row inmates in cases that often had nothing to do with terrorism, and in some instances who had been convicted of crimes going back to the 1990s, drew their final breaths without anyone in Islamabad even flinching, save a handful of activists, diplomats and journalists.

European leaders have tried - albeit unsuccessfully - to persuade the government to reinstate the moratorium, or at least to spare Shafqat Hussain, a prisoner caught up in a maelstrom involving the Peshawar massacre, trade interests and diplomatic relations.

Gaining GSP+ status has enabled Pakistan to grow its exports to Europe by $1 billion in a year. But the EU stands alone among Pakistan's strategic partners in campaigning for the abolition of the death penalty. Neither China nor Saudi Arabia or the United States, who all execute their own prisoners, want to rile Islamabad when it comes to capital punishment.

Click to watch on a portable device

After Peshawar, calls by the European Union, the United Nations and NGOs along with pressure by the media managed to stave off Shafqat Hussain’s execution four times. On Monday night, a fifth reprieve seemed likely when the leader of Pakistani Kashmir, Shafqat Hussain’s home region, pleaded for another stay of execution citing "humanitarian reasons".

But on Tuesday morning Shafqat Hussain mounted the scaffold and went to his death. Apart from a small ripple in the news, statements of outrage by NGOs and the desolation of his family, it was met with indifference. Has Pakistan really avenged the victims of the Peshawar massacre by executing Shafqat Hussain and hundreds of others like him who have been hanged? And will it really avenge spilt blood by killing thousands more prisoners?

Follow Guillaume Lavallée on Twitter.

(AFP Photo / Sajjad Qayyum)

(AFP Photo / Sajjad Qayyum)