Bjork’s ‘Army of Me’: music, and fame, on a wall

NEW YORK, March 13, 2015 - So how exactly do you put music on a wall? And is it even worth doing?

Those are the questions posed by the Museum of Modern Art, and which thousands of visitors will likely be pondering over the coming months, for what the New York institution describes as one of its most challenging projects ever – a retrospective on Bjork.

I headed to the show preview with the hope this would be mind-blowing – a pivotal artistic moment that blurs the lines between the aural and visual. Perhaps even a new model for museums seeking to fully encompass an artist’s breadth of work. Those were certainly the ambitions, and the end product is wondrously innovative.

Yet I came out with a sense that this was also an experiment in the reaches of pop culture hagiography, with one of the world’s most venerable museums giving in to the idea that a celebrity in herself is the most important aspect of art.

::video YouTube id='EiXQ5qaUGDI' width='620'::Running until June 7 the exhibition offers a stroll through the Icelandic singer’s eight solo albums since 1993 accompanied by an audio guide, which responds to sensors to narrate a fictional creation story about Bjork. The serene voice of Antony, lead singer of Antony and the Johnsons, beckons me to take my time and “slow down” to reflect on the music.

Statues border on kitsch

And at every turn, there’s Bjork. To an extent, that’s normal - the retrospective is about her. But her likeness is everywhere.

Statues of the singer - her face with a regal gaze - dominate the galleries to showcase some of her signature outfits. Bjork the Statue is wearing the swan dress from the 2001 Oscars, the dress of tiny bells designed by the late Alexander McQueen, and is tucked inside the Styrofoam body sculpture from the cover of her 2007 album “Volta” that loosely resembled both a psychedelic apple and platypus. Elsewhere, the cover of her 1997 album “Homogenic,” featuring Bjork in a kimono, blinks at you.

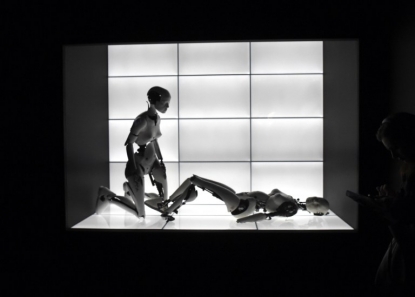

An exhibit at the MoMA Bjork show in New York (AFP Photo / Timothy A. Clary)

An exhibit at the MoMA Bjork show in New York (AFP Photo / Timothy A. Clary)These are not celebrity shots of Warholian irony. Instead, it borders on kitsch. Statues are the stuff of Disney theme parks, wax museums or small-town historical markers, not of the MoMA. Fashion designers would rightfully value the outfits, but why so many Bjorks? As I walked through, with Antony telling me to relax as I stood between a mass of fellow journalists and security guards, I found myself thinking of the Bjork lyric, “And if you complain once more/ You’ll meet an army of me.”

MoMA's first smartphone app

The museum’s lobbies play music from a Tesla coil and other “instruments” that appeared on Bjork’s 2011 album “Biophilia,” itself a groundbreaking work with its merging of themes of nature and technology. (The album came with a smartphone app - the first to enter the MoMA’s collections - that let users experience natural scenes, games and karaoke.)

Instruments in the MoMA Bjork show in New York (AFP Photo / Timothy A. Clary)

Instruments in the MoMA Bjork show in New York (AFP Photo / Timothy A. Clary)The Bjork retrospective certainly reveals the emotional depths of the singer’s most recent album, “Vulnicura,” through a video for the 10-minute song “Black Lake.” The audience enters a studio with speakers situated just in the right spots to maximize DJ Arca’s beats as they spark up the mournful strings. Two facing screens show Bjork, squatting in a copper-wire dress in a frigid Icelandic cave, as she bangs her head toward the ground and slams her fist on her chest. “Did I love you too much?” Bjork cries in the song, which like the rest of the album chronicles her mental journey as she ended her long relationship with artist Matthew Barney. “I did it for love / I honored my feelings / You betrayed your own heart / Corrupted that organ.”

An exhibit at the MoMA Bjork show in New York (AFP Photo / Timothy A. Clary)

An exhibit at the MoMA Bjork show in New York (AFP Photo / Timothy A. Clary)The song is beautiful, but as I listen to it, I can’t help but wonder - what’s Matthew Barney thinking? (Will he stop by casually to watch?) He’s one of the most prominent contemporary artists and has numerous works in the MoMA permanent collection – and designed shoes and a music box featured in the Bjork exhibition. But his time for a retrospective has not come at the MoMA.

Coveted museum space

Celebrities aside all this raises the broader question, one likely to nag at many artists of lesser renown than Barney, of whether so much of the world’s most coveted museum space should have gone to a 49-year-old musician.

On this point, I can’t see a solid case against Bjork as an artist worthy of a retrospective.

An exhibit at the MoMA Bjork show in New York (AFP Photo / Timothy A. Clary)

An exhibit at the MoMA Bjork show in New York (AFP Photo / Timothy A. Clary)The exhibition’s curator Klaus Biesenbach has described her as a paradigmatic figure of the 1990s. (He meant that as a compliment.) Perhaps we can now look back at the 1990s as a heyday for musical eclecticism. But in any case, Bjork’s sound (even, perhaps, her earlier work with the post-punk band The Sugarcubes) has been groundbreaking, with its intertwine of melancholy orchestration and serpentine intelligent beats and her sheer joy at breaking conventional songwriting formats – not to mention her uniquely powerful, three-octave voice.

And anyone who questions the wisdom of featuring a musician at the MoMA need only wander across to museum’s current exhibition on Jean Dubuffet. The French pioneer of “art brut” – who few would doubt belongs in the MoMA – relished in disorienting his audience by messing with their expectations of form.

An exhibit at the MoMA Bjork show in New York (AFP Photo / Timothy A. Clary)

An exhibit at the MoMA Bjork show in New York (AFP Photo / Timothy A. Clary)For Dubuffet, displacing art to unfamiliar surroundings was at least as important as the object itself. He contributed artwork to the dark, avant-garde symphony “The Pillory” by Jasun Martz (who later worked with Michael Jackson).

Still music, even on a wall

Dubuffet’s “Coucou Bazar,” which premiered at New York’s Guggenheim in 1973, was a live painting with dancers moving under jigsaw-piece costumes to the sounds of Turkish-born electronic composer Ilhan Mimaroglu. In an explanation at the time about “Coucou Bazar,” Dubuffet wrote that he hoped his live show would “not belong in the range of theater, but rather of painting.”

You could imagine the same thoughts coming 40 years later from Bjork and the MoMA - this is still about music, even if all you are looking is museum pieces. Yet Dubuffet was all about rejecting high art to embrace the creative impulses of the mentally ill and others outside the cultural mainstream. It is hard to see Bjork’s work in such ideological terms.

An exhibit at the MoMA Bjork show in New York (AFP Photo / Timothy A. Clary)

An exhibit at the MoMA Bjork show in New York (AFP Photo / Timothy A. Clary)Her imaginary biography, written by the Icelandic poet Sjon and played over the retrospective’s headsets, tells of a girl who was born in black sands and gains strength to defend the weak against the powerful. It’s a work of fiction, but still a frame of reference that I never associated with Bjork. She has spoken out for causes including gay rights and Tibet, but her defining trait is not heroism but creativity.

Even with the Army of Me omnipresent at the MoMA, the real, flesh-and-blood Bjork appeared only briefly at the preview for the show she worked on for so many years. She took a moment before the debut of her “Black Lake” video to thank the MoMA and other collaborators. Her face was barely visible, as she wore a dress that resembled several giant black sea cucumbers, joined together by a confining net. In the context of the retrospective, it was a moment of understatement.

Shaun Tandon is an AFP music correspondent based in New York

An exhibit at the MoMA Bjork show in New York (AFP Photo / Timothy A. Clary)

An exhibit at the MoMA Bjork show in New York (AFP Photo / Timothy A. Clary)