When terror unravels at home

(AFP Photo / Thomas Samson)

PARIS, January 11, 2014 - As a journalist, I've covered some dramatic events in the past -- natural disasters in China come to mind or the conflict in Ukraine. But I never thought I'd see a bloodbath in Paris, my home city.

Why was I -- am I still -- so shaken by Friday's siege at the Porte de Vincennes in Paris?

Selfishly, I realise that could well have been me getting up in the morning, toddling off to the supermarket, and ending up sprawled on the floor, mowed down by a man who apparently thinks killing innocent people is OK.

It's easier for me to relate to the four people who were killed by Amedy Coulibaly, than it is to the hundreds who were buried by a torrent of mud in Zhouqu or those who fell under sniper attack in Kiev.

Friday starts quietly enough -- if quiet is the right word with three gunmen on the loose somewhere in France, not far from Paris it seems.

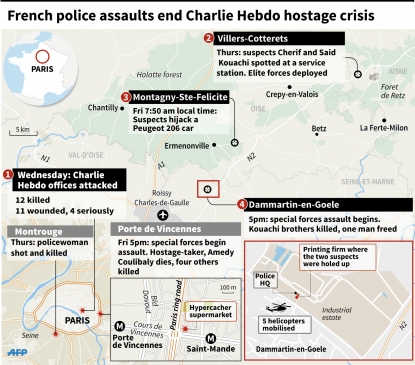

Then news breaks that the brothers who massacred 12 people at Charlie Hebdo's office on Wednesday are involved in a stand-off some 40 kilometres outside the French capital, and have taken a person hostage.

I let my colleagues deal with that chilling news and take off to the main Paris mosque after Friday prayers for a few routine vox-pops.

As I talk to a young man about the last few days' events, he looks at his phone and says: "did you know there's another hostage situation in Paris?". My blood runs cold.

Right on cue, my phone rings and the office tells me to rush to Porte de Vincennes, where shoppers in a Jewish supermarket have been held up by Coulibaly, the man suspected of shooting a policewoman Thursday.

Police forces taking position by the Hyper Cacher kosher grocery store (AFP Photo / Eric Feferberg)

Police forces taking position by the Hyper Cacher kosher grocery store (AFP Photo / Eric Feferberg)What? What? So he was here all along? I'd imagined him long gone, on the run, not a mere 10 kilometres from where he committed his crime.

And more worrying, is he linked to the brothers?

When I get there, police have already sealed off a large area surrounding the shop with its large, white "Hyper Cacher" sign.

But it's still visible from a bridge over the ring road that surrounds Paris, where curious onlookers and journalists are gathered, watching, waiting.

What strikes me first is the silence. The highway, normally chock-a-block with cars hurtling by at full speed, is completely empty on the two lanes nearest the supermarket.

On the lanes opposite, cars and trucks are stacked up in a long line, hastily abandoned, in a scene reminiscent of post-apocalyptic zombie movies.

Vehicles blocked on the Paris ring road on January 9, 2015 (AFP Photo / Stephane Jourdain)

Vehicles blocked on the Paris ring road on January 9, 2015 (AFP Photo / Stephane Jourdain)Up the car ramp that leads out of the highway to the supermarket, elite RAID police forces are crouched down, waiting.

Police tell us to move off the bridge, behind a building. But the shop is still visible across the highway from a small opening in between high-rises where people gather, craning their heads to see what's going on.

The atmosphere is one of morbid fascination mixed with anxiety. It's hard to believe that just 100 metres away, people are living through their worst nightmare, their lives hanging by a thread.

Police above the Paris ring road in Porte de Vincennes on January 9, 2015 (AFP Photo / Thomas Samson)

Police above the Paris ring road in Porte de Vincennes on January 9, 2015 (AFP Photo / Thomas Samson)That's when the rumours start swirling. "There's another situation at the Trocadero (near the Eiffel Tower)", one man says. "No that's rubbish," a woman responds, "my mate just passed there by car and nothing's going on."

"You from AFP?" one man asks. "You guys are saying two hostages are dead over there, but others are saying there are no casualties."

I just shrug, unable to tell him one way or another as I'm trying to avoid using the Internet to preserve my phone battery. Tragically, as it turns out, AFP was right.

A policeman takes aim at Porte de Vincennes in Paris on January 9, 2015 (AFP Photo / Thomas Samson)

A policeman takes aim at Porte de Vincennes in Paris on January 9, 2015 (AFP Photo / Thomas Samson)My battery decides to conk out anyway. Predictably, I have no charger with me.

So the rush to find a charger begins -- not for the new iPhone, I tell people, the 4S, the old one.

It seems so ludicrous -- I'm here, with the eyes of the world glued to the story, right next to the siege that could erupt at any time, and I may not be able to tell my newsroom. "My battery died" ain't going to cut it as an excuse.

Momentarily, I'm drawn away from morbid thoughts about the hostages and I focus on one thing -- the charger.

Police instruct local residents in Porte de Vincennes during the hostage siege on January 9, 2015 (AFP Photo / Eric Feferberg)

Police instruct local residents in Porte de Vincennes during the hostage siege on January 9, 2015 (AFP Photo / Eric Feferberg)I rush into a bakery, one of the only shops still open around here. Next door, a chemist has shuttered up and employees are holed up inside.

No, they don't have a charger. I speak briefly to a fellow journalist, a woman is crouching down next to him, both charging their phones. He can't help.

Luckily, in a hairdresser nearby, one woman has what I’m looking for. Hallelujah! She's having her hair done, metres away from a potential massacre. The casual scene seems wrong at a time like this, but at the same time it feels completely right. Life goes on.

There, I speak to another customer who was eating at McDonald's nearby when she saw police cars squealing by, gunshots fired. She and her mum were fast told to leave.

Residents being evacuated during the Porte de Vincennes hostage siege on January 9, 2015 (AFP Photo / Martin Bureau)

Residents being evacuated during the Porte de Vincennes hostage siege on January 9, 2015 (AFP Photo / Martin Bureau)Her car is still on the large avenue leading up to the siege, there is no way she is getting it back and she's preparing to spend the night in the area. She also has her hair done.

Many are in this situation, their flats nearby but inaccessible, their children stuck in schools, unable to get out... But no one moans about it. After all, they're not in that supermarket.

Suddenly, the manager of the hairdresser's shop says shots have been fired in Dammartin-en-Goele, where the two brothers are.

Special forces have obviously decided to move in there, so we're bracing for that to happen here too.

Sure enough, three loud bangs detonate, shaking the windows of the hairdresser's, and people scream.

::video YouTube id='er7rPjh-Ugs' width='620'::"Get inside," the manager shouts as I rush out, grabbing my lightly charged phone, calling the office.

Some of those who were craning their heads round a police cordon to try and catch a glimpse of the shop run away, terrified.

Gunfire bursts out, and more loud bangs are heard across the highway.

"It's war," one woman screams, dragging a little girl with her.

The terror is catching, my heart is thumping as I rush to the "viewing spot" I was at previously. I'm not scared for my own life -- I'm nowhere near danger -- I'm thinking of those inside.

Was the assault successful? Was it a bomb that exploded? Who was firing the shots? The police? Coulibaly? Both?

Special forces launch the assault in Porte de Vincennes, east Paris, on January 9, 2015 (AFP Photo / Thomas Samson)

Special forces launch the assault in Porte de Vincennes, east Paris, on January 9, 2015 (AFP Photo / Thomas Samson)As I run, I bump into the journalist I met charging his phone at the baker's. He works for the Ouest France daily.

He tells me breathlessly that the woman crouching down next to him -- the one I had caught a quick glimpse of -- had been crying.

Apparently, her boyfriend is one of the hostages. When she heard the bangs, she became frantic. He took her directly to the police, who took charge of her.

He's a journalist and her's is a juicy story, but he says he won't write a single line about her distress, he won't use a single quote. "She's my daughter's age," he keeps repeating, shocked.

(Ouest France did finally publish a witness account by the young woman, named Delphine, whose partner Yoav Hattab was among the victims of the killing, and who contacted the journalist after the attack).

Special forces evacuate hostages in Porte de Vincennes, Paris, on January 9, 2015 (AFP Photo / Thomas Samson)

Special forces evacuate hostages in Porte de Vincennes, Paris, on January 9, 2015 (AFP Photo / Thomas Samson)Calm returns. We find out the assault is over. That's when CNBC, which wants to interview me, calls. I'm still panting from the running.

I've fielded calls from all sorts of media over the years on breaking news stories, in various states of preparedness.

This is easy though, or so I think.

They ask me to describe the scene. Well I can't, I can't actually see anything. I'm really close but I can probably see less than them. Even the viewing point I was at before has been obscured by a police van.

The presenter ends up telling me what happened, how ironic!

So I describe the atmosphere, all the while walking to another place where I think I may be able to see something.

Special forces evacuate hostages in Porte de Vincennes, Paris, on January 9, 2015 (AFP Photo / Thomas Samson)

Special forces evacuate hostages in Porte de Vincennes, Paris, on January 9, 2015 (AFP Photo / Thomas Samson)There I bump into a man, Anass, who lives in the flat directly above the shop. His wife is holed up in there and he hasn't been able to go home.

When he heard the bangs, he too went into overdrive, frantically trying to get past police to get home. His wife is fine thankfully, he managed to get through to her.

He's quiet, obviously enormously shaken, and I feel a surge of empathy towards him.

I've often found that in hugely distressing situations, I'm surprised by what actually pulls at my heartstrings.

Seeing bodies lined up on Independence Square in Kiev didn't move me too much, seeing two large Cossacks beating drums during the mayhem did, hugely.

The countless mining disasters in China, the natural ones like the Sichuan earthquake were shocking, but what moved me most during my time in that country was an old man desperately trying to find his kidnapped son.

In this case, it's softly-spoken Anass, still carrying the baguette he was bringing home in a plastic bag.

"I know them all at that shop," he says, tears in his eyes.

Suddenly, police ask if there are any owners of cars left abandoned on the highway. They can go get them now.

I tell Anass to go with them, and he wants me to come too so I follow, thinking I will finally get a better view of things.

We walk towards the supermarket, past pools of blood. The car owners go fetch their vehicles and we walk on.

He leaves me, thanking me (for what? I wonder). And all of a sudden, I find myself among scores of armed police, right in front of the supermarket. No one has stopped me.

A forensic police officer by the bullet-riddled windows of the Hyper Casher store on January 9, 2015 (AFP Photo / Eric Feferberg)

A forensic police officer by the bullet-riddled windows of the Hyper Casher store on January 9, 2015 (AFP Photo / Eric Feferberg)It's mayhem in there. The sliding glass entrance is shattered, a trolley is on its side. A body lies right next to the cash desk. Before I can see more, police usher me away, understandably.

I phone those details into the office immediately.

Then, suddenly, it hits me again. This isn't China, this isn't Ukraine, this isn't a warzone. This is France, Paris. I normally witness death and destruction abroad, far, far away from my city.

Seeing it unravel here is something else entirely.

Marianne Barriaux is an AFP correspondent in Paris