Saying goodbye to a changing Russia

MOSCOW, July 7, 2014 - The train rattled its way through Siberia, the forest gave way to mountains, vast bridges spanned gurgling rivers and the journey, of thousands of kilometres, ran to-the-minute on time. At the stops, sometimes over an hour long, passengers dazed by sleep wandered out and bought smoked fish freshly snatched from local lakes and sold on the platforms to make an ad hoc supper washed down with beer.

And I thought, damn you Russia, I am really am going to miss you... Rossiya, ya budu po tebe skuchat.

It's true that Russia, and especially Moscow, can be a tough and frankly life-sapping place to live. The seemingly endless winter that begins in the sheer misery of the soggy November darkness; the sometimes inexplicably abrupt behaviour of people in public life; the traffic jams that turn any outing into an operation requiring military planning.

But as I travelled through Siberia on a valedictory journey and took stock of the memories from five-and-a-half years of living in this vast and often contradictory nation, I realised I could not imagine anywhere more enthralling on earth.

Russia is a country where you can take a plane from Vladivostok at eight in the the morning, watch the sun rising permanently from your window and then land in Moscow at pretty much the same time as you left.

Snowfall in the spring, Moscow, May 7, 2013. (AFP Photo / Yuri Kadobnov)

Snowfall in the spring, Moscow, May 7, 2013. (AFP Photo / Yuri Kadobnov)Momentous Change

It is a place that leaves indelible memories. The ski marathon amid the volcanoes of Kamchatka where I almost passed out. The golden stardust scattered by the ballet dancers of Russia's great theatres as their performances keep up a continuity going back to the Tsarist era. Those freezing late winter mornings when the sun turns everything to a gleaming silver and the tightly packed snow scrunches under the feet.

Russia is that limpid river where the lone fisherman in a rowing boat is the only person visible for miles around, it's that long distance train journey where nights blur into days, it's that forest that makes you feel the loneliest and happiest person in the world.

It's also -- and this is the dream of any journalist -- a country experiencing momentous change. But like a vertiginous fairground ride, it is impossible to judge from a contemporary viewpoint where this change is heading.

Special forces train in the Volgograd region, April 4, 2014. (AFP Photo / Andrey Kronberg)

Special forces train in the Volgograd region, April 4, 2014. (AFP Photo / Andrey Kronberg)From the outside, Russia can often be seen to be stuck in a post-Soviet time warp, those faces marching down the street that still seem hewn out of granite, that intransigent foreign policy blamed for a fair share of the world's problems.

And that leader -- I'll try here to write one piece about Russia that does not mention his name -- who just won't go away. And whose position has been immeasurably helped with the annexation of Crimea.

But the country is in a state of perceptible flux. The Internet flourished late in Russia but has now burst into life with social networks and blogs existing in their own Russian language micro-universe. What has now become taboo in the increasingly strait-laced press is discussed, no-holds-barred, by hundreds of thousands every day.

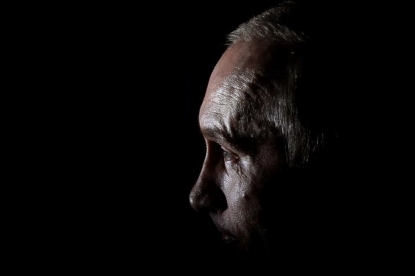

Vladimir Putin in December 2007 in Moscow. (AFP Photo / Dima Korotayev)

Vladimir Putin in December 2007 in Moscow. (AFP Photo / Dima Korotayev)Coming into adulthood now and taking their first jobs is that generation born after the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 and need not be burdened by the same Soviet inheritance as their parents. One day they will be leading the country, what kind of country we will see.

Despite all the official restrictions (a recent ban on swearing in the arts just the latest example of absurdity made real), Russia has one of the most thrilling cultural scenes anywhere. Just not always where you might expect. While headlines focused on the machinations at the Bolshoi Theatre and the megalomaniac tendencies of the over-stretched Mariinsky, the second tier Moscow Stanislavsky Theatre emerged as its most dynamic ballet company. The country's best arts festival takes place out in the city of Perm in the Urals and truly knows no artistic borders. And the theatre -- wow, don't get me started on the theatre -- is experimental, barrier breaking and increasingly not afraid of confronting the problems of contemporary Russia head-on.

A list of all the good things, some unexpected, in Russia could go on for sometime. The problem is that the list of the bad things risks being even longer.

Star Russian dancers Polina Semyonova and Leonid Sarfanov take a curtain call at the Mikhailovsky Theatre, St Petersburg. (Stuart Williams photo)

Hateful propaganda

The negative aspects are better known to the outside as they tend to be well-covered by the media. To name but a few -- the politicised judicial system, petty but still shocking racist beliefs held by a wide section of society, a church that has way too much political influence for its own good.

There is the hateful propaganda poured out by the television on news programmes every day of the week, not just anti-Western but vehemently anti-anyone who dares deviate from the mainstream be you gay, an opposition supporter or just someone who thinks differently. The Sunday evening news programme presented on Rossiya federal television seemed almost whackily extremist -- but then its frontman was named head of Russia's biggest news agency.

I've always tried to emphasise that in the West we underestimate the trauma that Russians experienced when the Soviet Union fell. But at the same time, attitudes towards history in Russia often range from willful ignorance to (more occasionally) a depraved distortion of the facts. Faced with the burden of the millions killed by Stalin, the authorities don't deny the facts they do something almost more dangerous by tacitly acknowledge the reality without ever making clear the enormity of this catastrophe.

Some of my English speaking, Western-leaning Russian friends paint the future in the most apocalyptic colours -- dictatorship, break-up of the country, even a domestic conflict. But I'm not sure -- my abiding impression of Russia -- without quoting Churchill's overused phrase about the riddle inside an enigma -- is that is beset by contradictions. Sometimes two steps forwards, one step back. Sometimes -- like over the last year I think -- one step forwards, three steps back. I think the country's future is hugely uncertain -- maybe more uncertain than any other major power in the world.

I had plenty of time to ruminate on my Trans-Siberian train journey. Russian trains are punctual but they are not fast. I was struck that almost everyone I met had never encountered a western European before. But the curiosity about the outside world was insatiable.

Classic Russian landscape at the family estate of national poet Alexander Pushkin in Pskov region, Western Russia. (Stuart Williams photo)

Changing perceptions

Judging by the questions I was asked, there is an astonishing sense of vulnerability in the national psyche, for all the outward breast-thumping swagger. Do people outside understand Russia's point of view on Ukraine? Don't you see how the Russian language is under threat? Russians are under threat. And China -- everyone feels the might of China rubbing against a weaker Russia. Do you have Chinese in your country?

2014 was a strange and jolting year in which to leave Russia. The Ukraine conflict set West and East against each other like at no other time since the Cold War. The authorities rushed to pass legislation cracking down on any counter current in civil society in a depressing routine that made the State Duma parliament look no better -- maybe even worse -- than its Soviet predecessor.

And there were the Olympics, which I covered in Sochi. They were going to be a disaster, everyone said, nothing would be ready. In the end, to cut a long story short, they were fantastic. A happy celebration of sport and community. I'd never seen foreigners and Russians mix in this way. People's ideas about Russia started to change, perhaps just a little.

Closing ceremony for the Winter Olympics in Sotchi, February 23, 2014. (AFP Photo / Peter Parks)

Closing ceremony for the Winter Olympics in Sotchi, February 23, 2014. (AFP Photo / Peter Parks)Then days after the closing ceremony came the de-facto invasion of Crimea. And all those soft power gains of good feelings were burned up in a matter of hours. But the authorities did not care -- for them soft power is for the weak, not the strong. With Sochi they had showed the home public they could impress the world. In the end that was all that mattered.

I leave Russia with the feeling that not only is the story far from over but in many ways only just starting. The Russian Federation as a state it only came into being after the collapse of the USSR in 1991 and as such is by far the youngest major power in the world. Without doubt, more tumultuous decades await the country. Its new story is only starting to be written. Meanwhile however, its magnificent limpid rivers will still flow, the ballet dancers shimmer and the the early winter snowflakes tumble down on the onion domes. That's my eternal Russia. Like it or not, the country infects your personal emotional memory like nothing else. For me, I know it is not really i proshchaite! (farewell!). It's more i poka, skoro uvidimsya esche (see you, we'll meet again soon!)

The name of slain Polish officer killed by Soviet NKVD in wartime Katyn massacre is exposed under the snow, Katyn forest, Russia. (Stuart Williams photo)

Former Moscow correspondent Stuart Williams has just started a new role with the agency in Istanbul.