Killing in a media blackout

LAGOS, January 30, 2015 - This week my colleague Celia Lebur travelled to Chad's border with Nigeria to hear the tales of men and women who escaped what may be the worst atrocity in Boko Haram's six-year Islamist insurgency, the assault on Baga.

There was Aisha Aladji Garb, a young mother nursing the tiny infant boy she delivered on a canoe, as she fled across Lake Chad, which forms the border, to the safety of a refugee camp.

Moussa Zira lay hidden in the bush among the dead bodies of his neighbours, after a bullet miraculously missed his head, before making his escape. Yacubu Moussa, a Christian pastor, spoke of "thousands" of fighters in the January 3 attack and of bodies littering the streets.

Nigerian refugee Aisha Aladji Garb and her newborn son in a UNHCR camp by Lake Chad on January 26, 2015 (AFP Photo / Sia Kambou)

Nigerian refugee Aisha Aladji Garb and her newborn son in a UNHCR camp by Lake Chad on January 26, 2015 (AFP Photo / Sia Kambou)The harrowing stories add to mounting eye-witness accounts that we've already been able to gather from Nigeria, pointing at killings on a mass scale in Baga. But the numbers - even now - are impossible to verify.

No-go zone

In Lagos, some 1,000 kilometres from the epicentre of the violence, news of a Boko Haram attack invariably starts with contact from one of our courageous local correspondents in northern Nigeria. Sometimes, the trigger can be a single line on social media.

What follows is a scramble for confirmation, which is not easy when the military and government have largely stopped talking about anything to do with the insurgency - unless it's on their terms.

Chadian soldiers patrol on January 21, 2015 at the Nigeria-Cameroon border as part of the military contingent against Boko Haram

(AFP Photo / Ali Kaya)

The fishing town of Baga in the far north of Borno is a no-go zone, as is much of the state, which has been worst hit by the violence.

No one can travel there, not even AFP's local Nigerian staff. Telecommunications are destroyed. The only option is for survivors of Boko Haram raids to make it to an area still under government control - like the Borno state capital, Maiduguri - or over the border into Chad to tell their stories. Sometimes that can take weeks.

Photos and video, the proof that seems to be increasingly required to establish beyond doubt that an attack took place? Forget it.

::video YouTube id='l0y6pCFji-g' width='620'::Cautious statement

Initial reporting of the attack in Baga went to type: AFP got word of the attack and issued a one-line alert on January 4. Beyond that, all we knew was that hundreds of people had fled and Boko Haram had overrun a military base used by Nigerian, Nigerien and Chadian troops in the counter-insurgency.

Four days later, President Goodluck Jonathan was in Lagos to launch his election campaign when Musa Bukar went on the Hausa-language service of BBC radio.

Bukar, a local government official from near Baga, claimed as many as 2,000 people may have been killed when Boko Haram fighters stormed the town, razing it and at least 16 surrounding settlements.

A screengrab taken on November 9, 2014 from a Boko Haram video shows the Islamist fighters parading in an unidentified town

(AFP Photo / Boko Haram)

AFP spoke to Bukar afterwards and he repeated his assertion. But he was unable to say how he arrived at the figure or give a breakdown of where and when the fatalities might have occurred.

The claim gained currency, though, when his quotes were translated into English and appeared on the BBC website. The following day, Amnesty International put out a cautious statement suggesting that - if the figure was correct - Baga could be the worst massacre in the insurgency.

In the days that followed, the guarded reporting of the BBC and Amnesty's caveats all but disappeared as social media grabbed hold of the story. In the rewriting, 2,000 became the established death toll and the world took notice, horrified.

A placard reading 'I am Charlie, let's not forget the victims of Boko Haram' at a rally in Abidjan on January 11, 2015,

following the attack on satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo (AFP Photo / Sia Kambou)

No one stayed to count bodies

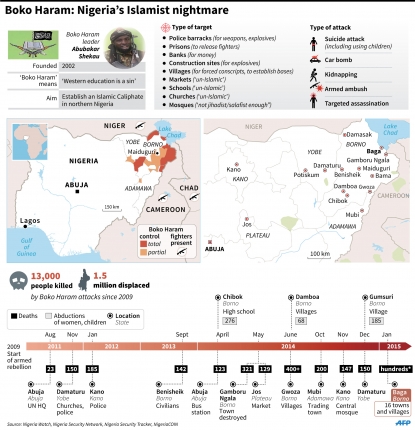

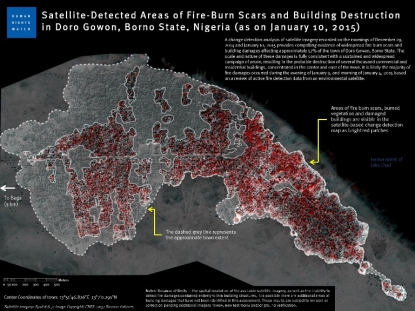

There's been a lot of attention paid to what happened in Baga - and rightly so. Amnesty and Human Rights Watch have published satellite images indicating the level of destruction. But even that couldn't give an accurate figure of the dead.

"No one stayed back to count the bodies," one Baga resident told HRW. "We were still running to get out of town."

In the West, we've grown used to authoritative statements, verified tolls of the dead and injured, official accounts of tragedy, almost in real time.

A satellite image made available by Human Rights Watch shows evidence of mass destruction around Baga, Nigeria.

View original here (AFP Photo / CNES 2015 Distribution Astrium Services / HRW)

Just a day before Jonathan's stump speech and Bukar took to the airwaves, Islamist gunmen burst into the offices of Charlie Hebdo, a satirical magazine, in Paris. Twelve people were killed.

The death toll and the number of injured was known within hours; President Francois Hollande was promptly on the scene; television cameras tracked the manhunt for the gunmen.

Mobile phone footage was uploaded and broadcast, eye-witness accounts repeated on a loop; the world's media flocked to Paris to cover the huge street protests and assess the importance of the attack and what it might mean.

None of this happens in Nigeria. For both the local media and the small group of foreign news organisations based here, including AFP, there's nothing comparable.

Bystanders look at dead bodies after a twin attack on a bus station in Abuja killed dozens of people on April 14, 2014 (AFP Photo)

Bystanders look at dead bodies after a twin attack on a bus station in Abuja killed dozens of people on April 14, 2014 (AFP Photo)Five attacks since Baga

The insurgency is now in its sixth year: there are estimates that between 4,000 and 10,000 people were killed last year alone but, really, no one knows for sure.

Since Bukar's interview, there have been five suicide bomb attacks in the northeast, including one involving a young girl thought to be aged just 10, a car bombing and multiple mass casualty attacks and abductions.

Zahra'u Babangida, a 14-year-old girl arrested in Kano with explosives strapped to her body after a suicide bombing,

seen at police headquarters on December 24, 2014 (AFP Photo / Aminu Abubakar)

Attacks have also taken place in northern Cameroon; Chadian forces have deployed to help while Nigeria and its neighbours are looking to mount a multi-national force in a sign that the risk to regional instability is being taken seriously.

Phones switched off

With each new attack we make calls to the military and the government, despite knowing that we'll likely be stonewalled.

Local military officials decline apologetically, saying they’re no longer authorised to speak and refer queries to Defence Headquarters in Abuja. But phones there are often switched off or ring out. Our texts often go unanswered or we’re told to check the military’s Twitter feed, where there’s usually nothing.

A screengrab taken on August 24, 2014 from a Boko Haram video allegedly shows people lined up to be executed by the group

(AFP Photo / Boko Haram)

That makes reporting the insurgency a complicated and frustrating process: like being handed a jigsaw with most of the pieces missing.

If an attack happens in a city such as Kano or Maiduguri, it's usually more straightforward – assuming the mobile phone network holds. But even then, any official statements usually downplay death tolls. Sometimes, the only option is to go to the hospital mortuary and count the bodies.

The day after twin suicide blasts hit the central mosque in Kano in November 2014 (AFP Photo / Aminu Abubakar)

The day after twin suicide blasts hit the central mosque in Kano in November 2014 (AFP Photo / Aminu Abubakar)When Boko Haram attacked Kano's central mosque last November, AFP did just that. We counted 92. A trusted rescue official later told us 120. Did more people die of their injuries afterwards? We don't know. It's likely.

But with attacks happening almost daily, it's just impossible for reporters to dwell on a single incident for long. There just isn't the time.

Children from Baga, Nigeria in a UNHCR camp in N'Gouboua, Chad on January 27, 2015 (AFP Photo / Sia Kambou)

Children from Baga, Nigeria in a UNHCR camp in N'Gouboua, Chad on January 27, 2015 (AFP Photo / Sia Kambou)Summarised in a hashtag

This may give a partial answer to those who have been wondering these past few weeks why Nigeria doesn't lead the news bulletins day after day after day.

There's not just the regularity of the attacks - another Boko Haram atrocity in Nigeria isn't going to knock a rare one in Paris off the front pages internationally - but the relentless lack of certainty.

Increasingly we like neat packages of information, something easily understood, with arresting images, that can be summarised in 140 characters or a hashtag.

In the Boko Haram insurgency, there’s never a complete picture, just snippets of unimaginable horror and an attempt to fill in the gaps before bracing for the next attack.

Phil Hazlewood is AFP bureau chief in Lagos