Journey to the top of the earth

The road to the desert plateaus at the most isolated corner of the Indian Himalayas is almost overwhelming in its otherworldly beauty. But I can say from experience that the scenery is harder to enjoy while hopelessly lost, in the middle of a rainstorm, and without a single other human in sight.

An Indian Air Force aircraft is seen against the backdrop of mountains surrounding Leh, the joint capital of the union territory of Ladakh, on June 27, 2020. - (AFP / Tauseef Mustafa)

An Indian Air Force aircraft is seen against the backdrop of mountains surrounding Leh, the joint capital of the union territory of Ladakh, on June 27, 2020. - (AFP / Tauseef Mustafa)We were nearing the end of a treacherous journey to the edge of Ladakh, a contested and sparsely populated territory subject to claims by China and Pakistan -- leading to occasional flashes of deadly conflict between India and its neighbours.

My colleague Money Sharma and I headed to the region after the latest bout of border violence in June, when a high-altitude bout of hand-to-hand combat with People’s Liberation Army troops left at least 20 Indian soldiers dead.

A family mourns a soldier killed in a clash with Chinese forces in June 2020 (AFP / Narinder Nanu)

A family mourns a soldier killed in a clash with Chinese forces in June 2020 (AFP / Narinder Nanu)Details of the incident are still murky, and months later the number of Chinese casualties in the confrontation remains unclear, but both sides have since deployed thousands of reinforcements and heavy weaponry to the frontier and the spike in cross-border tensions has yet to fully simmer down.

Our morning had started on the steep ascent towards the Shinku La mountain pass, almost 17,000 feet above sea level and nearly double the elevation of the day’s starting point at the small village of Keylong. For centuries, this rugged path has been the main route to the frontier for overland traders and travellers from Himachal Pradesh to the south.

Evening views in Keylong, a small transit town in India’s remote Lahaul and Spiti district, where we stayed in a deserted hotel.

(AFP / Bhuvan Bagga)

Evening views in Keylong, a small transit town in India’s remote Lahaul and Spiti district, where we stayed in a deserted hotel.

(AFP / Bhuvan Bagga)We were armed with a crude map but the helpful young man who had drawn it had been at pains to tell us how easy it was to get lost on the road to Chhika, our ultimate destination. And he was right.

When we finally arrived, hours behind schedule, the rain had turned into a downpour and the temperature had dropped below 15 degrees Celsius -- fine by European standards, but teeth-chatteringly cold compared to my home in New Delhi, and all the worse in our soaking wet clothes during our descent into the village, a slippery walk down a narrow staircase carved into the side of a mountain.

“Village” gives a generous estimation of the size of Chhika, which is really nothing more than a cluster of eight or nine stone houses decked in prayer flags; this part of the Himalayas, far closer to Tibet than the Indian plains, is one of the small redoubts of Buddhism in a country where four out of every five people are Hindu. We very much felt like outsiders, but an elderly man put us at ease as he rushed out from one of the homes to greet us, with all the exuberance of someone seldom given the chance to meet new people.

Our host was far less interested in who we were and news of where we had come from than how we had made the journey. The new road from Keylong that brought us to his doorstep had cut overland travel times to a fraction of what they were just a few years earlier. He told us that the last time he was sick, he’d had to walk all day to get to the nearest village in a journey that now takes half an hour.

The picturesque mountainscape of India’s far north has acted as a buffer between villages like Chhika and the lowland plains back towards Delhi and beyond. The Rohtang Pass, one of two roadways into the region, is locally known as “Pile of Corpses Pass” for the number of people who have died while trying to traverse it. Most people living here eke out a spartan living by foraging or growing root vegetables during the short summer months and bunkering down in their homes during the long winter.

But the road to Chhika is one sign that this isolation will soon be a thing of the past. India’s leaders have been startled by massive development on the other side of the Chinese border, along with the increase in tensions along the militarised frontier. Better transport into the region has long been considered a strategic necessity.

Rooftops in Shimla (AFP / Str)

Rooftops in Shimla (AFP / Str)

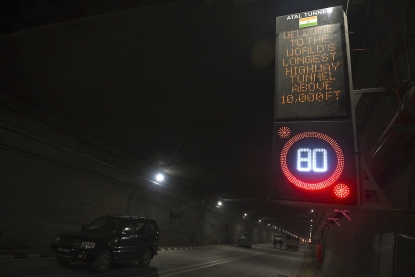

We had witnessed the pinnacle achievement of this new policy a day earlier during our drive to Keylong through the new nine-kilometre Rohtang tunnel: a decade in the making, it is the world’s longest road tunnel at an altitude above 10,000 feet and cuts the journey time towards the next big Himalayan town from eight hours to 90 minutes. It was formally opened in October by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who has cast himself as the protector of the nation and adopted a belligerent tone with China in the aftermath of June’s deadly border clashes.

A sign board welcomes the motorists inside the Atal Rohtang Tunnel near Solang in Himachal Pradesh state (AFP / Money Sharma)

A sign board welcomes the motorists inside the Atal Rohtang Tunnel near Solang in Himachal Pradesh state (AFP / Money Sharma)The Atal Tunnel is a true marvel of engineering, constructed in a low oxygen environment where temperatures often dip below freezing and the surrounding hills are prone to landslides. Colonel Parikshit Mehra, the tunnel’s project director, credits its success to overcoming the logistical challenge of procuring warm meals for the thousands of labourers: “They lift the spirits like nothing else can,” he told us.

Mehra is a military man, and the project was clearly dreamed up for martial reasons: thousands of troops can now be rushed into Ladakh in the event of another confrontation with one of India’s neighbours.

But all through this corner of the Himalayas, people spoke to us animatedly of the positive changes the new highways would bring: more tourists, better resources, better healthcare, and local jobs.

A man drives an excavator on the highway in Karakoram mountains connecting the Kashmir valley with Ladakh (AFP / Tauseef Mustafa)

A man drives an excavator on the highway in Karakoram mountains connecting the Kashmir valley with Ladakh (AFP / Tauseef Mustafa) Indian villagers plow a field with their yaks in the northern state of Himachal Pradesh (AFP / Xavier Galiana)

Indian villagers plow a field with their yaks in the northern state of Himachal Pradesh (AFP / Xavier Galiana)

“This is the only life we’ve known, but now things are changing,” said Ramesh Kumar Raulba, a district lawmaker who met us in Keylong.

“I can vividly remember how our people used to carry their belongings on horsebacks from distant towns across these mountains, often risking and losing their lives along the way,” he told us. “We couldn’t have imagined where we are today.”

In this photograph taken on July 7, 2018, an Indian man holds onto two sheep before butchering them along the banks of the river Spiti in the northern state of Himachal Pradesh (AFP / Xavier Galiana)

In this photograph taken on July 7, 2018, an Indian man holds onto two sheep before butchering them along the banks of the river Spiti in the northern state of Himachal Pradesh (AFP / Xavier Galiana)

It was a reluctant return to New Delhi after days of serenity and alpine air. I am one of 22 million people living in the capital, a city where last year the pollution was so bad that for a week we couldn’t see 20 metres in front of us. People are everywhere, nature is absent and the opportunities for quiet and solitude are negligible.

(AFP / Tauseef Mustafa)

(AFP / Tauseef Mustafa)When I gazed out at the postcard scenery of the Himalayas and breathed the fresh air, it was impossible for me not to glorify my surroundings and to feel anxious about what these changes may bring in their wake. I suspect that the next time I pass through these places, I will struggle to recognise them.

An Indian Buddhist monk looks out from Tnagyud Gompa monastery as the sun sets in Komik in Spiti Valley in the northern state of Himachal Pradesh (AFP / Xavier Galiana)

An Indian Buddhist monk looks out from Tnagyud Gompa monastery as the sun sets in Komik in Spiti Valley in the northern state of Himachal Pradesh (AFP / Xavier Galiana)This blog was edited by Sean Gleeson in Hong Kong