Inside the machine

Maungdaw -- As soon as we stepped off the plane, the cameras were rolling. Not our cameras. The government's.

It was mid-March and I was among a small group of journalists invited on a chaperoned tour of northern Rakhine state in Myanmar, the epicentre of the Rohingya crisis.

Rohingya refugees walk near the no man's land area between Bangladesh and Myanmar in the Palongkhali area next to Ukhia on October 19, 2017.

(AFP / Munir Uz Zaman)

Rohingya refugees walk near the no man's land area between Bangladesh and Myanmar in the Palongkhali area next to Ukhia on October 19, 2017.

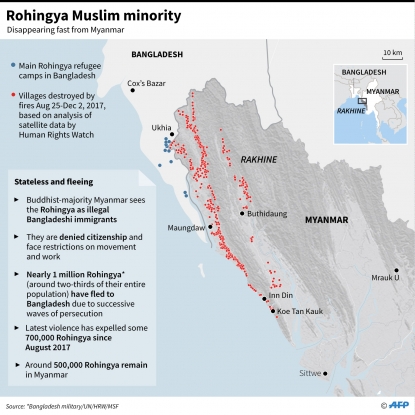

(AFP / Munir Uz Zaman)The area has been largely sealed off to the media since August 25 when insurgents from the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army attacked police posts.

The military responded with massive "clearance operations" that drove 700,000 Rohingya into Bangladesh. The US and UN have called the army crackdown ethnic cleansing.

Northern Rakhine had been hard to access even before those operations.

Myanmar's government, which denies committing atrocities against the Rohingya, has allowed only a handful of steered visits since the exodus started.

Like many journalists covering Myanmar, I have been to Bangladesh to interview Rohingya refugees.

But only glimpses of the devastation of northern Rakhine have emerged through satellite imagery and snatched video and photos from press trips.

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)I wanted to see it for myself. But there was - of course - a price. Joining the tour was a tacit agreement to be a part of Myanmar's PR machine.

The machine warps understanding of the crisis inside the country, adopts terms like "fake news" as ammunition, and portrays outside criticism as the product of misinformed foreigners weighing in on issues of Myanmar history and identity they can't possibly understand.

Excursions into northern Rakhine involve cherry picking sites that show the alleged brutality of the insurgents -- but less so the ruined lives of Rohingya.

Access is turned on and off like a tap. The rare invitations are constrained by time and resources. We relied on a government-hired translator, and the total amount of time we spent in the conflict area was two days - most of which was spent in a car getting from place to place.

Our presence helped Myanmar authorities send a message that the country was transparent. We were there to cover the news but to our handlers we were the news.

And so cameramen from state-backed media filmed our arrival on the tarmac in the Rakhine state capital Sittwe, as if we were celebrities as opposed to shabbily dressed journalists on assignment.

This handout photo taken on March 17, 2018, and released by Myanmar News Agency on April 3, 2018, shows a group of foreign journalists interviewing Muslim Rohingya residents during a government controlled trip in Maungdaw, near the Myanmar-Bangladesh border. (AFP / Myanmar News Agency/XGTY)

This handout photo taken on March 17, 2018, and released by Myanmar News Agency on April 3, 2018, shows a group of foreign journalists interviewing Muslim Rohingya residents during a government controlled trip in Maungdaw, near the Myanmar-Bangladesh border. (AFP / Myanmar News Agency/XGTY)As of this writing, state media have published more articles about the trip than AFP, describing our group as "independent media" to give the trip an air of credibility.

Knowing all this going in, the natural question is, why go at all?

The conditions for reporting were uncomfortable, but we decided they were worth it, because the horrors that have taken place deserve scrutiny -- albeit imperfect -- and there is always the chance of the Myanmar PR machine breaking down.

Our two days in Maungdaw district were meant to convince us that Myanmar was ready and willing to resettle refugees.

We drove up on a refurbished road, passing excavators, bulldozers and sweaty work crews.

There were clusters of new houses. In one village where villagers used to live in the hills, there was now a helipad.

In this photograph taken on March 18, 2018, government's newly built processing camp for minority Rohingya Muslims pasted with Myanmar and Chinese flag stickers is seen in Taung Pyo Letwe located in Maungdaw in Rakhine state near Bangladesh border as Myanmar authorities prepare repatriation process.

(AFP / Joe Freeman)

In this photograph taken on March 18, 2018, government's newly built processing camp for minority Rohingya Muslims pasted with Myanmar and Chinese flag stickers is seen in Taung Pyo Letwe located in Maungdaw in Rakhine state near Bangladesh border as Myanmar authorities prepare repatriation process.

(AFP / Joe Freeman)Organizers allowed us to visit the Myanmar side of "no man's land," where Rohingya refugees who refuse to go to either Bangladesh or back to Myanmar are sheltering.

Intended to be a quick trip due to time, it turned into a frenetic interview through the barbed wire fence with a Rohingya camp leader, who channelled the reluctance of refugees to come back without rights guaranteed to other Myanmar citizens.

Minority Rohingya Muslims gather behind Myanmar's border lined with barbed wire fences in Maungdaw district, located in Rakhine State bounded by Bangladesh on March 18, 2018.

(AFP / Joe Freeman)

Minority Rohingya Muslims gather behind Myanmar's border lined with barbed wire fences in Maungdaw district, located in Rakhine State bounded by Bangladesh on March 18, 2018.

(AFP / Joe Freeman)On the border, we were shown trailers that Rohingya refugees would transit through, with processing equipment and biometric scanning machines.

One official used a pointer as if in a geography class to show us a map explaining the whole repatriation process.

There was a lot to see and they were eager to be accommodating to our requests, which led me to realize that Myanmar's PR may perhaps be less a sinister and sophisticated plot than a genuine failure to grasp the enormity of the problem, a sense that if they only told their side of the story, all would be well.

In one village slated for several-hundred Rohingya returnees, there were only three houses standing, and construction started only a few weeks ago. We stood asking questions to a local administrator within view of the former village of the residents, which lay in fire-blackened ruins. He said he didn't know who torched the village. He calmly answered questions and officials offered us a snack as we left.

In this photo taken on March 18, 2018, the closed Friendship Bridge linking Myanmar and Bangladesh is seen from Maungdaw in Rakhine state. (AFP / Joe Freeman)

In this photo taken on March 18, 2018, the closed Friendship Bridge linking Myanmar and Bangladesh is seen from Maungdaw in Rakhine state. (AFP / Joe Freeman)But it's what we didn't see that started to stand out.

Burnt remains of houses and abandoned buildings lined roads and dotted abandoned fields, in a landscape described by one journalist on the trip as looking "like Mars."

Myanmar says it has approved more than 500 Rohingya - from 700,000 refugees - to come back from Bangladesh. But so far only a handful have gone home, and since they came from no man's land where Bangladesh doesn't have jurisdiction, it is clear repatriation has not really commenced. Rights groups also worry that those who do return will be stuck in camps that the government has insisted are temporary not permanent.

A Rohingya refugee walks in the mud at Thangkhali refugee camp in Bangladesh's Cox's Bazar district on September 17, 2017.

(AFP / Dominique Faget)

A Rohingya refugee walks in the mud at Thangkhali refugee camp in Bangladesh's Cox's Bazar district on September 17, 2017.

(AFP / Dominique Faget) Rohingya Muslim refugees who were stranded after leaving Myanmar walk towards the Balukhali refugee camp after crossing the border in Bangladesh's Ukhia district on November 2, 2017.

(AFP / Dibyangshu Sarkar)

Rohingya Muslim refugees who were stranded after leaving Myanmar walk towards the Balukhali refugee camp after crossing the border in Bangladesh's Ukhia district on November 2, 2017.

(AFP / Dibyangshu Sarkar)

Pockets of Rohingya remain, hemmed in by hostile neighbours and running out of money and work.

"There are not many people left here," one Rohingya man told us when the government agreed to let us stop at Ngan Chaung village in Maungdaw, where two dozen Rohingya residents had already been assembled to greet us.

"Many people are fleeing to the other side but a few people are left. It is so difficult to work here," he said.

Something else not as visible but palpable: anger. Myanmar can build houses and helipads, but rebuilding trust and mending ties with the ethnic Rakhine Buddhist community will take more than money.

This photograph taken on September 12, 2017 shows Rohingya refugees arriving by boat, as smoke rises from fires on the shoreline behind them, at Shah Parir Dwip on the Bangladesh side of the Naf River after fleeing violence in Myanmar.

(AFP / Adib Chowdhury)

This photograph taken on September 12, 2017 shows Rohingya refugees arriving by boat, as smoke rises from fires on the shoreline behind them, at Shah Parir Dwip on the Bangladesh side of the Naf River after fleeing violence in Myanmar.

(AFP / Adib Chowdhury) A Bangladeshi man helps Rohingya Muslim refugees to disembark from a boat on the Bangladeshi shoreline of the Naf river after crossing the border from Myanmar in Teknaf on September 30, 2017.

(AFP / Fred Dufour)

A Bangladeshi man helps Rohingya Muslim refugees to disembark from a boat on the Bangladeshi shoreline of the Naf river after crossing the border from Myanmar in Teknaf on September 30, 2017.

(AFP / Fred Dufour)

One of the last places we stopped was Inn Din. The village is the only place Myanmar has admitted that its security forces took part in the extrajudicial killing of 10 Rohingya men on September 2.

Two Reuters journalists investigating the deaths were arrested and charged with violating the Official Secrets Act before their article on the atrocities was published.

Some 6,000 Rohingya used to live in the village, but all have fled, leaving under 1,000 ethnic Rakhine Buddhists behind.

"We can't accept them (the Rohingya)" any more, said U San Hlaing, an elderly Rakhine resident.

Rohingya refugees walk through a shallow canal after crossing the Naf River as they flee violence in Myanmar to reach Bangladesh in Palongkhali near Ukhia on October 16, 2017.

(AFP / Munir Uz Zaman)

Rohingya refugees walk through a shallow canal after crossing the Naf River as they flee violence in Myanmar to reach Bangladesh in Palongkhali near Ukhia on October 16, 2017.

(AFP / Munir Uz Zaman)The coastal village still has traces of beauty, with palm trees and scenic views.

I wandered out in the direction of the water from the Bay of Bengal, tired of being filmed while interviewing, but also frustrated at how much we hadn’t been able to report. I wanted the trip to be worth it, but I had a gnawing feeling of missing something. I still do.

I passed an abandoned Muslim cemetery with empty bottles and other detritus piled at the edges.

Down a nearby path, only the foundations of houses could be seen, along with tree stumps and old clothes scattered about.

In this photograph taken on March 18, 2018 during a Myanmar government arranged press tour, charred debris of houses and vegetation are seen in the abandoned village of minority Rohingya Muslims in Inn Din located in Maungdaw, in Rakhine state near the Bangladeshi border.

(AFP / Joe Freeman)

In this photograph taken on March 18, 2018 during a Myanmar government arranged press tour, charred debris of houses and vegetation are seen in the abandoned village of minority Rohingya Muslims in Inn Din located in Maungdaw, in Rakhine state near the Bangladeshi border.

(AFP / Joe Freeman)The day afterwards, state media described our visit there in one sentence: "the media group arrived in Inn Din Village and met with local ethnics (Rakhine) who were the victims of terrorist attacks."

There was no mention of the Rohingya who died there. But there was a picture of us.

Rohingya refugee cries as she walks after crossing the Naf river from Myanmar into Bangladesh in Whaikhyang on October 9, 2017.

(AFP / Fred Dufour)

Rohingya refugee cries as she walks after crossing the Naf river from Myanmar into Bangladesh in Whaikhyang on October 9, 2017.

(AFP / Fred Dufour)