Heartbreak at the hajj

DUBAI, October 14, 2015 -- When I landed in Saudi Arabia in September, it was to cover the hajj for the third time in my five years at AFP. It never occurred to me that I would end up reporting on the worst ever tragedy in the historyof the sacred pilgrimage that would leave more than 1,500 faithful dead.

September 24 was just like any typical day I had experienced in Mina, as people greeted one another on the first day of the Muslim Eid al-Adha festival.

I had just returned to the information ministry camp after a long walk under the scorching sun, coming from the site where worshippers stone the devil -- one of the rituals performed during the hajj -- with my two friends and colleagues, AFP photographer Mohammed al-Shaikh and video journalist Mohamad Ghandour.

We were about to start settling in and resting after two exhausting nights when I received a telephone call from our Riyadh bureau chief Ian Timberlake telling me that the civil defence was reporting more than 100 people killed in a stampede in Mina.

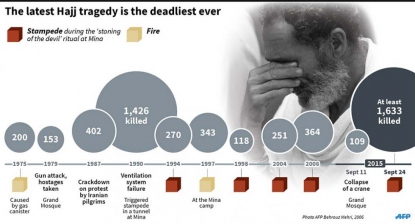

I will always remember the incredible adrenaline rush and panic I felt at that moment. For a few seconds, I was in denial, convinced that the report must be a rumour. Just a few weeks earlier, a crane had crashed into the Grand Mosque in Mecca, killing over a hundred people and to me, two disasters linked to the hajj just couldn't happen in one month.

An aerial view shows the Grand Mosque in Mecca, where an accident with a crane left more than 100 dead this year. (AFP / Mohammed Al-Shaikh)

An aerial view shows the Grand Mosque in Mecca, where an accident with a crane left more than 100 dead this year. (AFP / Mohammed Al-Shaikh)I immediately called my two colleagues and we hurried out with the information ministry guide, who usually accompanies us from the minute we land in the kingdom right until we leave, recording all our movements and imposing restrictions on our coverage. Temperatures were soaring above 45 degrees Celsius. Later they would be partly blamed for the high death toll.

Mina is a valley lined with camps where the pilgrims stay and where only official vehicles are allowed; everyone else moves on foot. Because of this, the sounds of sirens and helicopters wailing day and night are quite familiar across the town as police try to control the crowds, making it difficult to tell if there is a real emergency.

The hajj has known stampedes in the past, but during the past few years the pilgrimage has gone off without incident, with the last crush in Mina occurring a decade ago. Since then, the authorities have spent billions of dollars massively expanding the site that attracts Muslims from the world over each year.

The pilgrim tent camp at Mina in February, 2004. (AFP / Awad Awad)

The pilgrim tent camp at Mina in February, 2004. (AFP / Awad Awad)The stampede site itself was very far away from our camp so our first instinct was to reach the emergency hospital, which took an almost half-hour walk in the heat.

We saw helicopters landing atop the hospital as the roads below were jammed with dozens of ambulances.

Finally at the Mina Emergency Hospital, chaos prevails with one ambulance arriving after the other as medics run around with stretchers and security officials shout out orders.

Ambulances with pilgrims injured in the stampede arrive at the Mina hospital. (AFP / Mohammed Al-Shaikh)

Ambulances with pilgrims injured in the stampede arrive at the Mina hospital. (AFP / Mohammed Al-Shaikh)“If I catch you taking one more picture I swear I’ll smash your camera,” one security official barks out at Mohammed al-Shaikh. After contacting several health ministry officials for permits to take pictures at the hospital, we are finally asked to leave and return “at night or even better, tomorrow.”

We do, and take some footage and pictures from behind the surrounding fence.

As we return to the information ministry camp, we are told that all other reporters had been locked in for hours and that journalists, apart from those of the Saudi Al-Ekhbariya channel, were not allowed to leave.

Information ministry officials appeared confused over how to deal with the media during a crisis of such magnitude, amid rumours that it wasn't a stampede at all. “It’s probably an attack by the Islamic State group,” an elderly man whispers to me.

Nearly 10 hours after the stampede, reporters were finally allowed to visit the site of the tragedy, an official Saudi guide accompanying every group, including ours.

An Iranian woman mourns during a funeral procession for stampede victims. (AFP / Atta Kenare)

An Iranian woman mourns during a funeral procession for stampede victims. (AFP / Atta Kenare)We finally reach the area, a narrow street lined with tents and surrounded by a high fence. Many of those caught in the crush reached for that fence to escape, often relying on raw instinct to survive.

Hamza Musa Kabir, a 55-year-old from Kano in northern Nigeria was pinned down by a huge man and with his shroud preventing him from untangling himself. He slipped the shroud off and tried to grab the hand of a fellow Nigerian on top of the fence, but that man couldn't pull him up because of the huge man on top of Kabir.

Desperate, he grabbed the man's testicles "and squeezed them which made him to jump off me," Kabir would later say in a calm, emotionless voice. "This enabled me to use my other hand to reach for the metal bar of the fence and grab it." Another man on the fence helped hoist him up and Kabir then passed out in a nearby tent.

(AFP)

A melting pot for countless cultures, hajj gatherings never cease to fascinate me with every visit.

Many pilgrims, coming from as far as China, are travelling for the first time ever in their lives to fulfill this once-in-a-lifetime religious duty, which for many is a lifelong dream.

It is only in this huge world gathering where I would be talking to a group of Rwandans when Macedonian pilgrims would pass by nodding and smiling.

Muslim pilgrims circle around Islam's holiest site, the Kaaba, at the Grand Mosque in Mecca. (AFP/Mohammed Al-Shaikh)

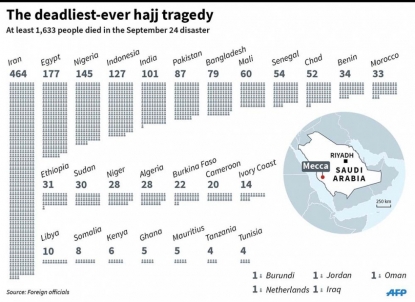

The diversity was reflected in the toll figures, with nationals from more than 30 countries reported killed by various nations. The death toll, based on statements of foreign nations, has so far reached 1,633, far more than the 769 provided by Saudi Arabia.

Saudi authorities have launched a formal investigation into what happened, and have defended themselves against criticism by saying the kingdom has made great efforts to care for pilgrims, millions of whom arrive every year for the hajj, which is performed annually around the Eid Al-Adha festival, and another pilgrimage called the umrah, which can be undertaken at any time of the year.

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)When we got to the site of the stampede, a human chain of security forces was blocking entry to the accident site, where dead bodies were said to be still lying around.

The mood was somber in this part of Mina, where pilgrims who have witnessed the stampede still appeared in shock.

AFP’s Kano correspondent Aminu Abubakar, who happened to be performing the pilgrimage and was there at the time of the incident, escaped the crush of bodies because he was at the head of a procession.

“There was no room to manoeuvre,” he said.

Witnesses recounted horrifying details of children dying despite parents’ efforts to save them by throwing them on tent-tops and survivors spoke of their attempts to climb the surrounding fence.

Click here to watch this video on a mobile device

A Libyan witness who survived with his mother was accusing the Saudi police of negligence. Fellow pilgrims gathering around the camera were nodding in approval. The policemen deployed are “trainees,” he says. “They don't even know the roads and directions.”

He wasn’t the first to complain this year of the poor organization. I had been hearing similar remarks from pilgrims even in Arafat, on the peak of hajj the day before.

Having covered hajj last year, during which authorities appeared in complete control of the crowds, I also noticed a difference this year.

Despite their big numbers, members of the security forces were doing little to help pilgrims this year, apart from spraying dehydrated passers by with water and shouting out “move hajji move” to any pilgrim trying to get some rest.

Saudi emergency personnel spray water to cool down the pilgrims in soaring temperatures. (AFP / stringer)

Saudi emergency personnel spray water to cool down the pilgrims in soaring temperatures. (AFP / stringer)I would never forget the terrified, forlorn, and at times angry looks I have seen on the faces of the stampede witnesses I met that day.

Many were gathering around our team, asking that we hear them speak of the ordeal.

They wanted to be heard. They spoke loudly, blaming Saudi authorities for the incident. I was surprised they would dare criticize the kingdom -- an absolute monarchy, where speaking one's mind can be punished harshly if authorities don't like what is being said -- right in front of the military police.

"There are more soldiers than pilgrims, but there is no organisation, not here and not in Arafat,” said green-eyed Egyptian pilgrim Ahmed, in his 30s.

“The Saudi government is responsible. It is spending so much money on hajj just to boast and for its princes to show off…” His voice trails off as the ministry guide intervenes angrily shouting out that we should end the interviews and leave.

“I’m not afraid of anyone, I want to speak,” shouted back Ahmed as security officials began gathering closer and ushering us away.

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)The next day, rituals at the Jamarat Bridge went by normally amid heavier security deployment. And just a few miles away from the stampede site, a group of policemen gathered when they saw us carrying cameras and asked us to take their pictures. They began grinning and posing before one of their chiefs saw them and yelled at us to leave.

At the emergency hospital that day, health officials and nurses appeared unsure who the patients they had were and whether they had arrived from the stampede site or for other reasons.

The nurses were having trouble communicating with patients from all over the world.

In one room, lay an elderly Indian man, whose head had stiches. He would repeatedly say: “I am not good” and show us his bleeding nose. Asked what he was suffering from, his Saudi nurse who could not understand his language, would just giggle and say “He’s ok. He just worries too much.”

An injured pilgrim is admitted to Mina hospital after the stampede. (AFP / Mohammed Al-Shaikh)

An injured pilgrim is admitted to Mina hospital after the stampede. (AFP / Mohammed Al-Shaikh)In the corridors and at the reception, worried family members of the victims come in and out trying to find out the fate of their missing loved ones.

I still wonder how the stories of those ended. Did they find them at the morgue where they were sent to search? Or were they lucky enough to find them in a hospital bed?

There have been many stories on how the stampede happened. But what is known for a fact is that two massive blocs of pilgrims had collided at the site, prompting a wave of panic. As one Nigerian survivor told me from his hospital bed, they all began “running for their lives.”

Lynne Al-Nahhas is an AFP correspondent based in Dubai.

A relative of a missing victim shows her picture as he searches for her at Mina hospital after the stampede. (AFP / Mohammed Al-Shaikh)

A relative of a missing victim shows her picture as he searches for her at Mina hospital after the stampede. (AFP / Mohammed Al-Shaikh)