A floating Tower of Babel in the Arctic

By Clement Sabourin

(This is the third post in a series. You can read the first here and the second here.)

Barrow Strait, October 2, 2015 - With a crew of 24 scientists from around the world, the CCGS Amundsen is a veritable Tower of Babel, with a strong sense of camaraderie permeating throughout the big red ship.

Everyone is quite charming and easy to get along with. Harmony is bolstered by the military precision with which everything is done, even though Canada's coast guard is unarmed (except for rifles to ward off polar bears) and has no naval or law enforcement responsibilities (those are left to the navy).

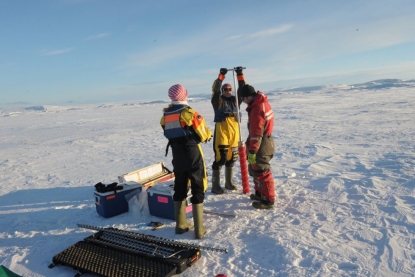

Sailor Hugo Jacques guards against polar bears as scientists work on the ice (AFP / Clement Sabourin)

Sailor Hugo Jacques guards against polar bears as scientists work on the ice (AFP / Clement Sabourin)Safety and security are top priorities: landlubbers are given a briefing when they first come aboard on what levers to pull to sound an alarm if someone falls overboard, or how to use a fire extinguisher to fight a fire in the engine room. A notice above each bed points to the closest lifeboat in case of an order to abandon ship.

Meal time is also a serious affair: the day starts at 7:30 a.m. with breakfast served in the crew cafeteria or officers' mess. On the menu today: bacon and eggs, hash browns, pancakes, cheese and croissants. Lunch is served at noon, followed by dinner at 5 p.m. Every Sunday night, the captain hosts a special dinner to break up the monotony of life at sea and maintain the same rhythms of life that the crew will eventually return to back onshore.

Scientists take measurements in the ice (AFP / Clement Sabourin)

Scientists take measurements in the ice (AFP / Clement Sabourin)At sea, the crew work 12-hour days. They are usually away from friends and family for four to six weeks at a time. Then another set of crew comes aboard for a new rotation and the ship goes on.

On this mission, "B crew" is in charge, under the command of Alain Lacerte, an old sea dog well liked by both his crew and passengers. You can usually find him in the wheelhouse overlooking the bow of the ship, where the helmsman and the first mate set course changes. On a nearby table, there are a litany of communication devices, including a phone from the 1950s and the latest satellite phone. They pour over charts, satellite images and compass readings, mapping out a safe course through the Arctic, much of which remains uncharted for navigation.

A helicopter takes Amundsen scientists onto the ice floes (AFP / Clement Sabourin)

A helicopter takes Amundsen scientists onto the ice floes (AFP / Clement Sabourin)Apart from mission head Roger Francois and the ship's officers, everyone aboard shares a cabin with a bunk bed, a television, desks and a washbasin (showers are communal). Some of the scientists have been aboard for three months. One must be very social to forgo any privacy for such a long period. Many go long periods without sleep, conducting experiments into the wee hours.

My cabin mate on this journey is Preston Pangun, an Inuit hunter from Kugluktuk and a Canadian Ranger (an Arctic military reserve force that patrol the far north). He's here monitoring wildlife and can be found most days with binoculars in hand scouting the sea ice for signs of animal life, scribbling in a notebook the times and places they were spotted. He can detect a seal in choppy waters from a long distance, knows all of the names of birds that pass overhead, and quickly identifies polar bear tracks on nearby sea ice. A father of three, he is eager to reunite with his family after this job is finished at the end of the week (weather permitting), and repair his snowmobile before the snow comes.

(AFP / Clement Sabourin)

(AFP / Clement Sabourin)Aboard this floating laboratory, there is little time to waste. But there are brief pauses in experimenting while the Amundsen travels from one scientific hotspot to another. To pass the time, the scientists like to watch movies -- dystopian fiction is their favorite -- watch satellite feeds of rugby matches, knit, exercise or read in their cabin. Some take the time to work on their doctoral thesis.

Then it's back to saving humanity from a climate crisis.

A polar bear makes its way across the ice (AFP / Clement Sabourin)

A polar bear makes its way across the ice (AFP / Clement Sabourin)