Dreams crushed by a beast

PALENQUE, Mexico, July 28, 2015 – It is 35 degrees out, and the humidity is close to 100 percent. We are tracking a freight train known as “La Bestia” (The Beast), as it rumbles from the southern border of Mexico towards the United States. This train is part of the history of migration. Hundreds of thousands have ridden it in pursuit of their American dream. Many have been attacked, robbed, mutilated or even killed in the process.

The train is moving at more than 40 km/h as it passes through the station in Tenosique, much too fast for the dozens of young migrants hoping to hoist themselves on board.

We set off in pursuit of the youths – myself, a text reporter and a photographer. We run beside them in the darkness, along the tracks. Only one manages to cling on. A dozen others, several of them minors, are left dejectedly behind. Some are angry, others resigned: this is not their first try.

Migrants are seen on board a train in Salto del Agua, Chiapas State on June 19, 2015 (AFP Photo / Alfredo Estrella)

Migrants are seen on board a train in Salto del Agua, Chiapas State on June 19, 2015 (AFP Photo / Alfredo Estrella)It’s a frustrating experience for us, too. We are here to film youths clinging onto the train. We have only five days - already a luxury - to document the migrant crisis in this region, where countless children risk the difficult and dangerous journey to Mexico’s far north. We also want to report on the rising numbers of arrests and what rights groups have denounced as violent police raids targeting migrants.

In the distance, we spot a teenager walking in the dark. I approach him. He eyes me suspiciously, glancing at my video camera. He has no time to talk, he says. He is trying to reach the next town along the railroad. I let my camera fall down below my shoulder, and engage him in conversation. Juan opens up, little by little. As I sense the trust building, step by tentative step, my camera finds its way back up onto my shoulder.

Click here to view on a mobile device

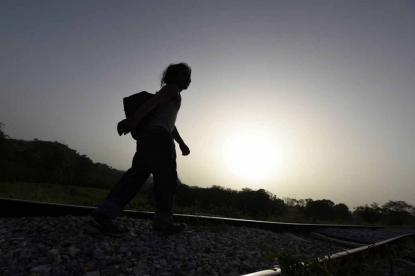

Like tens of thousands of central American minors, Juan is fleeing the violence, gangs and drugs plaguing his native Honduras. He looks like a child, hands hooked through the straps of his backpack. But his words are those of an adult. “I’m not afraid,” he tells me. “If they kill me, they kill me. But I’m going to keep moving.”

We part ways around 10 pm, leaving him on the tracks at Tenosique as we return to our hotel, exhausted by a 14-hour day spent chasing the iron monster. Juan walks on into the night, despite the exhaustion of 600 kilometres travelled in a few days.

A migrant walks in Chacamax, Chiapas state, Mexico, on June 21, 2015 (AFP Photo / Alfredo Estrella)

A migrant walks in Chacamax, Chiapas state, Mexico, on June 21, 2015 (AFP Photo / Alfredo Estrella)The following day, our hunt for La Bestia resumes. We follow its tracks, from station to station, through remote villages and rural lanes. Nothing to report. At least nothing that has not been shown many times before.

But these past two days we have seen dozens and dozens of migrants struggling along narrow trails, weighed down by the hundreds of kilometres they have already travelled, and the thousands that still lie ahead.

Migrants walk along the train tracks in Palenque, Chiapas State on June 19, 2015 (AFP Photo / Alfredo Estrella)

Migrants walk along the train tracks in Palenque, Chiapas State on June 19, 2015 (AFP Photo / Alfredo Estrella)Ethical principles in reporting can sometimes look different when you are out in the field. Can you, should you intervene in the awful human situations you are witnessing? Can you allow yourself to influence the lives of people whose story you are telling?

Off-camera moments, building trust

We decide to get involved. We offer water, bananas and biscuits to the migrants we meet. We tend to one person’s blister, to another who cut themself on branches while running from the police, yet another who suffered a deep gash to the head falling from La Bestia, or another with a nasty insect bite…

These off-camera moments also feed into our work. Those are the times when migrants tell us about their lives, their dreams, their problems. Some will later agree to be filmed. Others prefer to remain anonymous. Sometimes trust is built through the simplest human interactions.

AFP reporters perform first aid on a migrant in Chiapas State in June 2015 (AFP)

AFP reporters perform first aid on a migrant in Chiapas State in June 2015 (AFP)It’s a Saturday. We’re in Palenque, 80 kilometres further north. Night has fallen. There in the moonlight, dozens of migrants are spread out along the rails, on the lookout for the train. Alfredo, our photographer, approaches a group to make contact. One of them turns out to be Juan.

A human face to the tragedy

It’s a journalistic opportunity: a chance to put a human face – that of childlike Juan - on the plight of tens of thousands of kids. We can follow a slice of the life of this young migrant, from his arrival in Mexico, to the point where he boards a train heading north.

But you can’t humanise a story without getting close to the person in question. We spend a long time talking with the young Honduran, our cameras switched off.

Migrants wait for a train in Palenque, Chiapas state, Mexico, on June 20, 2015 (AFP Photo / Alfredo Estrella)

Migrants wait for a train in Palenque, Chiapas state, Mexico, on June 20, 2015 (AFP Photo / Alfredo Estrella)We share coffee and cigarettes. We talk about God, about the future. A fleeting camaraderie grows between us. When a complete stranger shares with you their closest secrets, it’s bound to trigger a strong of dose empathy – something reporters cannot always allow themselves. How could you possibly report on the worst human tragedies if you let every story eat you up inside?

Beaming, victorious

The train gets moving. Without a moment’s hesitation, Juan and his companions start running, trying to find the best spot to jump on board. Nothing - not stones or branches - will keep them from scaling the iron monster that could take them to their American dream.

Migrants travel on board of a train in Palenque, Chiapas state, Mexico, on June 20, 2015 (AFP Photo / Alfredo Estrella)

Migrants travel on board of a train in Palenque, Chiapas state, Mexico, on June 20, 2015 (AFP Photo / Alfredo Estrella)Our photographer and I set off in pursuit. Juan runs, jumps over prickly bushes, stumbles, picks himself up, and finally manages to grab onto a ladder. Alfredo and I run, trip but manage to get a picture of this instant. Juan has tamed the train. He waves down at us, beaming, victorious.

He knows we are here to film police raids. He also knows we have witnessed part of his dream.

AFP reporter Daphne Lemelin jumps from a train in Palenque, Chiapas State after filming migrants on board on June 20, 2015 (AFP Photo / Alfredo Estrella)

AFP reporter Daphne Lemelin jumps from a train in Palenque, Chiapas State after filming migrants on board on June 20, 2015 (AFP Photo / Alfredo Estrella)Ten kilometres down this road, which we’ve travelled before in pursuit of the train, we spot a vehicle belonging to the immigration police. We approach with our headlights off – a heated debate taking place in our car. Should we let them know we are here. Should we hide?

We go for a half-way solution. Slowly, we cross the tracks. The police and other men in plain clothes are getting ready for a raid. Some are armed with guns, others with truncheons.

An agent of the Mexican Immigration Service during an operation in San Mateo, Chiapas State on June 20, 2015 (AFP Photo / Alfredo Estrella)

An agent of the Mexican Immigration Service during an operation in San Mateo, Chiapas State on June 20, 2015 (AFP Photo / Alfredo Estrella)The wait begins. We are on a tiny side road that appears only as a faint, thin line on my satellite navigation system. Luckily, there is a phone signal. One of us alerts the human rights committee that a police raid is taking place in our vicinity. Another sends our satellite position to the AFP bureau in Mexico.

Surrounded by the police

"OUUUUUUT". The train is here. La Bestia draws to a halt with a groan. My camera is running. I want to capture every second of this. We approach the tracks – slightly worried the police could turn on us.

Migrants are detained by the Mexican Immigration Service in San Mateo, Chiapas State on June 20, 2015 (AFP Photo / Alfredo Estrella)

Migrants are detained by the Mexican Immigration Service in San Mateo, Chiapas State on June 20, 2015 (AFP Photo / Alfredo Estrella)Police aim their flashlights at the wagons, at the simple dwellings nearby and the surrounding rainforest. I film the officers at work, watching out of the corner of my eye in case some of the migrants try to make a run for it. A group of them is surrounded by the police.

A look that says 'Traitors'

"Get down, get down!” We see Juan forced to climb off the train. His hopes in tatters yet again.

In the light of my camera, he seems lost, miserable and angry all at once. The immigration police lead him away, along with his unfortunate companions, towards the “perrera” – the dog pound as their van is known. Some of the migrants, who shared coffee and stories with us, give us a look that to me says: “Traitors - you gave us up.”

Migrants are detained by the Mexican Immigration Service in San Mateo, Chiapas State on June 20, 2015 (AFP Photo / Alfredo Estrella)

Migrants are detained by the Mexican Immigration Service in San Mateo, Chiapas State on June 20, 2015 (AFP Photo / Alfredo Estrella)The van’s door slams shut on Juan’s American dream. He will be deported to Honduras. For the second time.

The camera is still running.

Back in the car, the adrenalin is starting to fall back down. And a question is gnawing at us. Should we have tried to warn them of the raid? Should we have asked for their phone numbers to do so? Even if we had those numbers, would we have made the call?

Migrants on board a train in Chacamax, Chiapas State on June 21, 2015 (AFP Photo / Alfredo Estrella)

Migrants on board a train in Chacamax, Chiapas State on June 21, 2015 (AFP Photo / Alfredo Estrella)The question stays hanging there. The camera is off. We get going again.

Since we did not warn them, we are better able to tell the story of these thousands of migrant kids, facing immense danger in hope of a better life. Because we didn’t warn them, Juan will be deported to Honduras. And will start all over, without missing a beat, in his attempt to reach the United States.

This teenaged boy whose dream was crushed by a train holds a special place in the labyrinth of my memories as a journalist. Juan is a tragedy with a human face, the human face of a tragedy.

Daphné Lemelin is an AFP-TV journalist based in Mexico

Migrants board a train in Palenque, Chiapas State, Mexico, on June 19, 2015 (AFP Photo / Alfredo Estrella)

Migrants board a train in Palenque, Chiapas State, Mexico, on June 19, 2015 (AFP Photo / Alfredo Estrella)